| The Children of Men | |

|---|---|

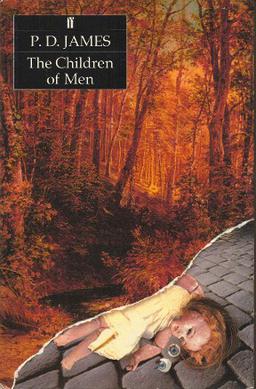

First UK edition

| |

| Author | P. D. James |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian novel |

| Publisher | Faber & Faber (UK) Alfred A. Knopf (US) |

Publication date

| 1992 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 241 pp |

| ISBN | 0-679-41873-3 |

| OCLC | 26214321 |

| Dewey Decimal | 823/.914 20 |

| LC Class | PR6060.A467 C48 1993 |

In the year 2027, eighteen years since the last baby was born, disillusioned Theo (Clive Owen) becomes an unlikely champion of the human race when he is asked by his former lover (Julianne Moore) to escort a young pregnant woman out of the country as quickly as possible.

- Starring:Clive Owen, Julianne Moore

- Directed by:Alfonso Cuaron

- Runtime:1 hour 50 minutes

- Release Date:Jan 3, 2007

- Studio:NBC Universal

- Rating:

Plot summary[edit]

The narrative voice for the novel alternates between the third person and the first person, the latter in the form of a diary kept by Dr. Theodore "Theo" Faron, an Oxford don.

The novel opens with the first entry in Theo's diary. It is the year 2021, but the novel's events have their origin in 1995, which is referred to as "Year Omega". In 1994, the sperm counts of human males plummeted to zero and mankind now faces imminent extinction. The last people to be born are now called "Omegas". "A race apart," they enjoy various prerogatives. Theo writes that the last human being to be born on Earth has been killed in a pub brawl.

In 2006, a man called Xan Lyppiatt, Theo's rich and charismatic cousin, appointed himself Warden of England in the last general election. As people have lost all interest in politics, Lyppiatt abolishes democracy. He is called a despot and a tyrant by his opponents, but officially the new society is referred to as egalitarian.

Theo is approached by a woman called Julian, a member of a group of dissidents calling themselves the Five Fishes. He meets with them at an isolated church. Rolf, their leader and Julian's husband, is hostile, but the others – Miriam (a former midwife), Gascoigne (a man from a military family), Luke (a former priest), and Julian – are more personable. The group wants Theo to approach Xan on their behalf and ask for various reforms, including a return to a more democratic system. During their discussions, and as Theo prepares to meet with Xan, the reader learns how the UK is in 2021:

- The youngest generation, the "Omegas", are described as spoiled, over-entitled and egotistical due to their youth and the luxurious lifestyle they are treated to. They are violent, remote and unstable, and regard non-Omegas (elders) with undisguised contempt, yet are spared punishment due to their age. According to rumour, outside of Britain some countries sacrifice Omegas in fertility rituals.

- Due to the global infertility of mankind, newborn animals (such as kittens and puppies) are doted upon and treated as infants, being pushed in prams and dressed in children's clothing. The latest trend in London is to have elaborate christening ceremonies for newborn pets.

- The country is governed by decree of the Council of England, which consists of five people. Parliament has been reduced to an advisory role. The aims of the Council are (1) protection and security, (2) comfort, and (3) pleasure—corresponding to the Warden's promises of (1) freedom from fear, (2) freedom from want, and (3) freedom from boredom.

- The Grenadiers — formerly an elite regiment in the British armed forces – are the Warden's private army. The State Secret Police (SSP) ensures the Council's decrees are executed.

- The courts still exist, but juries have been abolished. Under the "new arrangements", defendants are tried by a judge and two magistrates. All convicted criminals are dumped at a penal colony on the Isle of Man. There is no remission, escape is almost impossible, visitors are forbidden and prisoners may not write or receive letters.

- Every citizen is required to learn skills, such as husbandry, which they might need to help them survive if they happen to be among the last human beings in Britain.

- Foreign workers are lured into the country and then exploited. Young people, preferably Omegas, from poorer countries come to England to work there. These "foreign Omegas" or, generally, "Sojourners" are imported to do undesirable work. At 60, which is the age limit, they are sent back ("forcibly repatriated"). British Omegas are not allowed to emigrate so as to prevent further loss of labour.

- Elderly/infirm citizens have become a burden; nursing homes are for the privileged few. The rest are expected and sometimes forced to commit suicide by taking part in a "Quietus" (Council-sanctioned mass drownings) at the age of 60.

- The state has opened "pornography centres". Twice a year, healthy women under 45 must submit to a gynaecological examination, and most men must have their sperm tested, to keep hope alive.Theo's meeting with Xan, which turns out to be a meeting with the full Council of England, does not go well. Some of the members resent him because he resigned as Xan's advisor rather than share the responsibility of governing the UK. Xan guesses that Theo's suggestions came from others and makes clear to Theo that he will take action against dissidents.The Five Fishes distribute a leaflet detailing their demands. Theo is visited by the SSP and, shortly afterwards, sees Julian in the market. He tells her of the SSP visit, then tells her that if ever she needs him she only has to send for him. That night, however, Theo decides to leave England for the summer and visit the continent before nature overruns it.Soon after Theo's return, Miriam tells him that Gascoigne was arrested as he was trying to rig a Quietus landing stage to explode. The other Fishes are about to go on the run, and Julian wants him. Miriam reveals why Julian did not come herself—she is pregnant. Theo believes that Julian is deceiving herself, but when the two meet, Julian invites Theo to listen to her baby's heartbeat.During the group's flight, Luke is killed while trying to protect Julian during a confrontation with a wild gang of Omegas. Julian confesses that the father of her child is not Rolf, but the deceased Luke. Rolf, who believes he should rule the UK in Xan's place, is angered at the discovery; he abandons the group to notify the Warden.The group heads to a shack Theo knows of. Miriam delivers Julian's baby – a boy, not a girl as Julian had thought. Miriam goes to find more supplies; after she is gone too long Theo investigates. He finds Miriam dead, garrotted in a nearby house. Theo returns to Julian, but soon after Julian hears a noise outside – Xan.

- Theo and Xan confront each other and both fire one shot. The sudden wailing of the baby startles Xan, causing him to miss as Rolf had thought the baby would not be born for another month. Theo does not miss. He removes the Coronation Ring, which Xan had taken to wearing as a symbol of authority, from Xan's finger and seems poised to become the new leader of the UK – at least temporarily. The other members of the Council are introduced to the baby, and Theo baptises him.

Adaptations[edit]

A loose film adaptation, directed by Alfonso Cuarón and starring Julianne Moore and Clive Owen, was released in 2006. The film was well received and P.D. James herself was said to have been pleased with it despite the alterations.[2] - No one should have to choose between Clive Owen and P. D. James. As an alcoholic, unshaven hero in a totalitarian near-future, Mr. Owen holds together the ominous yet vibrant new film “Children of Men,” adding to his list of brooding, darkly handsome characters (notably in “Closer”). But while this Alfonso Cuarón film is inspired by the 1992 James novel, the movie is so purely cinematic, and its plot departs so widely from the book’s, that the screen version may obscure how wonderfully rich and unlikely that novel is.“The Children of Men” is not another of Ms. James’s famed detective novels, and it is not, as it has sometimes sloppily been described, science fiction. It is a trenchant analysis of politics and power that speaks urgently to this social moment, a 14-year-old work that remains surprisingly pertinent. Mr. Cuarón and Mr. Owen have made a film that works superbly apart from the book, but Ms. James’s extraordinary novel deserves to be rediscovered on its own.

- http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/28/movies/28men.html?_r=0

- In both forms “Children of Men,” which opened Monday, is a story of redemption, set in England just decades in the future (the film takes place in 2027), when women have inexplicably lost the ability to become pregnant. Utterly cynical, Theo (Mr. Owen) is drawn into a group trying to protect a woman who has, just as inexplicably, become pregnant and whose child is likely to be used for the despotic government’s own purposes.Ms. James couldn’t have foreseen some details the film uses to create a future frighteningly like today: a government department called Homeland Security; a crawl at the bottom of the omnipresent video screens that says, “Terror Alert: Extremely High.”But the social problems she could spot in 1992, like immigration, are even more disturbing now because they are more topical. A member of the novel’s ruling Council of England makes a comment that could come from a right-wing radio show in America today. “Remember what happened in Europe in the 1990s?” he says. “People became tired of invading hordes,” who expect to “exploit the benefits which had been won over centuries by intelligence, industry and courage.”Those prescient social themes give the book its resonance, and are far more important than the deft way the movie streamlines the novel: Theo, an Oxford historian in the James version, is a minor bureaucrat in the film’s Ministry of Energy; Julianne Moore’s character, who enlists his help in protecting the pregnant woman, combines two people from the novel, Theo’s ex-wife and a former student he scarcely knows.

- As she does so gracefully in her mysteries, in “The Children of Men” Ms. James creates a beautifully realized world, making fine points the film has no time for: childless women push dolls in baby carriages, and couples hold christening ceremonies after the births of kittens.And Theo recalls boyhood summers as the poor relation visiting his rich, supremely self-confident cousin, Xan, a character who as an adult holds the title warden of England and is, in fact, the country’s dictator. On screen this character, called Nigel and played byDanny Huston, has only one scene, when Theo tries to use this connection to get a travel visa for the pregnant woman.Moviegoers may wonder why this character pops up at all, or why such an elaborate set was created; we see that he owns Picasso’s “Guernica” and Michelangelo’s “David,” whose leg has been damaged. The episode feels shoehorned into the movie, which isn’t surprising in a work with five credited screenwriters and a nine-year gestation. Even after Mr. Cuarón became interested, in 2001, he went off to direct “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” before returning to the project, which was then altered to suit the post-9/11 world.Despite those topical additions, Xan is a huge lost opportunity for the film, because he is the vehicle for Ms. James’s astute exploration of how certain kinds of tyrants come to exist. The social disorder and pessimism that Ms. James defines so sharply — science has failed to explain, much less cure, the infertility, and religion is a solace to some but a gaping hole to others — has allowed this despot to seize control. Parliament is a sham that, as Theo says, “gives the illusion of democracy,” and the members of Xan’s ruling Council never disagree with him.

- This poisonous rule is presented to the public and accepted as a strong, desirable response to threats to the country. The government justifies abuses in the name of a smoothly run society: it condones the forced, slavelike labor of immigrants and encourages the mass suicides of the old. As a Council member explains: “What we guarantee is freedom from fear, freedom from want, freedom from boredom. The other freedoms are pointless without freedom from fear.”That line becomes even more haunting now that the world feels more threatening and freedom has become a buzzword applied to everything from the ludicrous anti-French Freedom Fries to the sober Freedom Tower planned for the World Trade Center site.The personal motives behind Xan’s tyranny are also shrewdly analyzed. Theo asks the once apolitical Xan why he became Britain’s ruler, and Xan answers in the cavalier manner we recognize from his boyhood, “At first because I thought I’d enjoy it,” adding, “I could never bear to watch someone doing badly what I knew I could do well.” By the time power had lost its thrill, he claims, no one in the Council was competent to take over.When Theo calls him on this self-delusion, Xan replies, “Have you ever known anyone to give up power, real power?”Theo fully grasps this explanation and carries its lesson to the underground group that hopes to overthrow Xan’s tyranny. “If you did succeed, what an intoxication of power,” he says.

- That warning comes back to haunt the entire novel, and it’s a theme the film could have put to fuller use. In its second half the screen version of “Children of Men” all but abandons its social concerns. (We see that immigrants have been forced into camps, but how and why?) It becomes a thoughtful chase movie. And even with Mr. Owen’s tough yet stirring performance, Theo is more conventional on screen. Like the film character, the book’s Theo has also lost a small child, but he has been responsible for the death, no state for a movie hero to be in.When the film loses its energy for politics and its taste for ambiguity, that makes the difference between a good movie and an exceptional one. (There are lesser reasons; was it necessary for two characters actually to say, “Jesus Christ” when learning of the near-miraculous pregnancy and birth?)The ending of the novel is brilliantly ambiguous and entirely different from the film’s, as the potential for the “intoxication of power” falls into unexpected hands. As Ms. James said in an interview when the book came out: “The detective novel affirms our belief in a rational universe because, at the end, the mystery is solved. In ‘The Children of Men’ there is no such comforting resolution.” It is comforting for both moviegoers and readers, though, to have Clive and P. D. as the season’s best odd couple.

- http://www.internetwritingjournal.com/p-d-james-pleased-with-film-version-of-children-108071

P.D. James Pleased With Film Version of Children of Men

January 8, 2007We heard that you weren't interested in doing a science-fiction project at first. Is that true?Cuarón, who is best known to general audiences for being the director of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban has a reputation for being respectful of an author's work. J.K. Rowling reportedly was happy with his work and he is in the running to direct another Potter film. Children of Men -- which we can't wait to see -- is playing in theaters nationwide.

Cuarón: True. I was not interested in the project. I didn't respond to the material. I was not interested in doing science fiction. ... The book takes place in a very posh universe. I love [P.D.] James, but I couldn't see myself doing the movie. Nevertheless the premise kept on haunting me, for weeks and weeks and weeks. ... I used the book as a jumping-off point.

Did you divert a lot from the book?

Cuarón: Yes. In the book Kee doesn't exist; it's [the] Julianne Moore [character] who was pregnant, and we just took a big departure there. ... We did have to honor the part of the story of the immigration [addressed in the book], but we created the whole thing with the refugees. We took the book as a point of departure to look at the state of men now, and added things like the Homeland Security and the whole idea of what is happening outside in the world.

Did the author see the final version of the film?

Cuarón: She did see the final version, and it is quite different, and she said she is proud to be associated with the film.

Category:Dystopian novels

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dystopias are sometimes found in science fiction novels and stories. Please see the article dystopia for discussion of definition. Note that there is no one definition of dystopia that is agreed upon by all, as the term is usually used to refer to something much more specific than simply a nightmare world or unpleasant future.

Entries should only be added to these category if their article clearly states that they are dystopian.

See also: Category:Utopian novels.

Subcategories

This category has the following 12 subcategories, out of 12 total.

BD | FHLN | N cont.PSW |

Pages in category "Dystopian novels"

Pages in category "Dystopian novels"

The following 200 pages are in this category, out of 280 total. This list may not reflect recent changes (learn more).

(previous 200) (next 200)123A

B

C

D

Children of Men

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the 1992 novel by P. D. James, see The Children of Men.

Children of Men is a 2006 dystopian science fiction film co-written, co-edited and directed by Alfonso Cuarón and based loosely on P. D. James's 1992 novel The Children of Men. In 2027, two decades of human infertility have left society on the brink of collapse. Illegal immigrants seek sanctuary in the United Kingdom, where the last functioning government imposes oppressive immigration laws on refugees. Clive Owen plays civil servant Theo Faron, who must help a West African refugee (Clare-Hope Ashitey) escape the chaos.Children of Men also stars Julianne Moore, Michael Caine, Pam Ferris, and Chiwetel Ejiofor.

The film was released on 22 September 2006 in the UK. It was released on 25 December in the US, where critics noted the relationship between the Christmas opening and the film's themes of hope, redemption and faith. Regardless of the limited release and low earnings at the box office compared to its budget, Children of Men received wide critical acclaim and was recognised for its achievements in screenwriting, cinematography, art direction and innovative single-shot action sequences. It was nominated for three Academy Awards: Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Cinematography andBest Film Editing. It was also nominated for three BAFTA Awards, winning Best Cinematography and Best Production Design, and for three Saturn Awards, winning Best Science Fiction Film.

P L O T

Plot[edit]

In 2027, after 18 years of global human infertility, civilization is on the brink of collapse as humanity faces the grim reality of extinction. The United Kingdom, the only stable nation with a functioning government, has been deluged by asylum seekers from around the world, fleeing the chaos and war which has taken hold in most countries. In response, Britain has become a militarizedpolice state as British forces round up and detain immigrants. Theo Faron (Clive Owen), a former activist turned cynical bureaucrat, is kidnapped by a militant immigrants' rights group known as the Fishes. Their leader turns out to be his estranged American wife Julian Taylor (Julianne Moore), from whom he separated after their son died from a flu pandemic in 2008.

Julian offers Theo money to acquire transit papers for a young refugee named Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), which Theo obtains from his cousin Nigel (Danny Huston), a government minister. However, the bearer must be accompanied, so Theo agrees to escort Kee in exchange for a larger sum. Luke (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a Fishes member, drives them and formermidwife Miriam (Pam Ferris) towards the coast to a boat. They are ambushed by an armed gang and Julian is fatally shot. Luke kills two police officers who stop their car and they escape to a safe house.

Kee reveals to Theo that she is pregnant—the only known pregnant woman on Earth. Julian had told her to only trust Theo, intending to hand Kee to the "Human Project", a supposed scientific group in the Azores dedicated to curing infertility. However, Luke persuades Kee to stay. That night, Theo eavesdrops on a meeting of Luke and other members and discovers that Julian's death was orchestrated by the group so they could use the baby as a political tool to support the coming revolution. Theo wakes Kee and Miriam and they steal a car, escaping to the secluded hideaway of Theo's aging hippie friend Jasper Palmer (Michael Caine), a former editorial cartoonist who cares for his wife, a former photojournalist who became catatonic after being brutally tortured several years before.

A plan is formulated to board the Human Project ship Tomorrow which will arrive offshore from the Bexhill refugee camp and Jasper proposes getting Syd (Peter Mullan), a camp guard he knows, to smuggle them. The Fishes trail the group and Jasper stays behind to stall them, giving the government-issued suicide drug Quietus to his wife. Before escaping with Miriam and Kee, Theo is horrified to witness the Fishes murder Jasper, but is forced to move on. They eventually meet Syd, who transports them to Bexhill disguised as prisoners. When Kee begins having contractions on a bus, Miriam distracts a suspicious guard by feigning mania and is taken away.

At the camp Theo and Kee meet a Romani woman Marichka (Oana Pellea), who provides a room where, that night, Kee gives birth to a girl. The next day, Syd finds them in their room and informs Theo and Kee that war has broken out between the British Army and the refugees, including the Fishes. He also attempts to capture them, having learned that they have a bounty on their heads, but Marichka and Theo fight him off and the group escapes. Amidst the fighting, however, the Fishes capture Kee and the baby. Theo tracks them to an apartment under heavy fire from the military and escorts her out. Awed by the baby, the combatants temporarily stop fighting, enabling them to escape. Marichka leads them to a boat in a sewer and Theo rows away. As they watch the bombing of Bexhill by the Royal Air Force from a distance, Theo reveals to Kee that he had been shot in the fighting. Kee tells Theo she will name her baby Dylan, after Theo's late son. Theo slowly dies from his wounds as the Tomorrow approaches through the fog.

I thought director Alfonso Cuarón's film of P.D. James' futuristic political-fable novel was good when it opened in 2006. After repeated viewings, I know Children of Men is indisputably great. A hypnotic Clive Owen starred as a resistance leader pinning his hopes on the last pregnant woman on Earth. Is it possible to capture the terrible absence of a world without children? Cuarón did it. No movie this decade was more redolent of sorrowful beauty and exhilarating action. You don't just watch the car ambush scene (pure camera wizardry) — you live inside it. That's Cuarón's magic: He makes you believe.

http://www.metroactive.com/metro/01.10.07/alfonso-cuaron-0702.html

Making the Future

Richard von Busack talks to Alfonso Cuarón about filming 'Children of Men'

Alfonso Cuarón's ménage-a-trois/road movie Y tu mamá también was the arrowhead of the Mexican new wave, currently startling the world. The mightily talented Cuarón's confident camera work, wit and sensuality make him a director who one is certain will be climbing to bigger heights in the coming decade.

His new film, Children of Men, is an exhilarating vision of the near future. Here he discusses the roots of the fantasy and its applicability to today's troubles.

CUARÓN: P.D. James' book is a Catholic allegory, so Children of Men's title comes from a quote of the Bible. The quote is, eh—I don't remember.METRO: What does the title ofChildren of Men mean?

We drifted apart from the book in an early stage. From the book we took the premise of infertility, a premise I understood as a metaphor for the failed sense of hope humanity has. We used themes that are shaping the first decade of the 21st century. And we can't go far without touching on the themes of environment and immigration.

Immigration is a global issue, but the problem of this issue is that it has an ideological tendency. In the recent past, the influx of immigrants were beneficial for the economy. The problem is that politicians need to create issues and causes, and they try to kindle these fears of otherness and the fear of the guys who are going to take your land ...

I have to question the ethics of borders when there is humanity in need. When we start segregating ourselves from what humanity needs ... we lose more and more of the sense of humanity as a whole. Now global warming is coming, and environmental issues are going to create new migrations.

I'm a Mexican. There's been a constant migration between Mexico and the United States. And the anti-immigration laws are getting tougher. The United States is clinging to archaic solutions, instead of trying to find new structures. The same country that praises that tearing apart of the Berlin Wall is building a single wall between the Mexico and the States. It's an expensive and archaic solution, and like all such solutions it will completely backfire.

Historically, a good percentage of these Mexicans try to earn their money and try to go back to their country. What's happening now is that it's tougher to go home, you might as well bring the whole family and stay here. There are a lot of people who want to move, but there are more of them that don't want to move. There is a constant economy of displacement in Mexico.

Mexico has the same issues with Guatemala and Central and South Americas, and in many ways the situation there has been more cruel ... that's what I'm trying to say, it's not a local issue, it's an issue that's affecting the world. As with global warming, there's a state of denial about the whole thing.

METRO: Why England as the site of this negative future in Children of Men, then. Why not Mexico?

CUARÓN: We're using England as a Green Zone, a comfort zone; the characters feel they're lucky to live there, but there's a big percentage of outsiders waiting to get in.

METRO: Speaking of England, the third Harry Potter movie, The Prisoner of Azkaban, is the best one according to J.K. Rowling. How did you do it?

CUARÓN: Guillermo del Toro pushed me to do it. He said, "You need to be clear on this. If you're going to do it, you need to honor and serve the material. If you do that, you'll make the movie great."

METRO: Serve the material!? But your movie had the most personality of any of the series.

CUARÓN: We had a great production designer. And we had Rowling. She has all this geography in her mind. The thing that we wanted to do was something we hadn't seen. We hadn't seen all of Hogwarts except in bits and pieces, and there were feelings you were watching a set. Let's link the spaces, let's allow audiences—even if they don't consciously know it—to experience the geography of the place. They'll know that if there's a corridor, there's going to be a clock, and if you go past the clock, there is going to be a courtyard, and beyond that, a bridge, and then down to the mountain, there is Hagrid's hut. We did something similar in Y tu mamá... and Children. There are very few close-ups. We tried to make Hogwarts a character.

METRO: The guerrilla war scenes in Children of Men had rare shock to them; they're some of the finest I've seen. You didn't sacrifice horror for spectacle.

CUARÓN: We used the cameras in the same principle as in Y tu mamá ...we decided social environment is as important as character, so you don't favor one over the other. That means going loose and wide. The camera doesn't do close-ups. Rather than make tension between the character and the environment, you make the character blend in with the environment.

The other rule of Y tu mamá ... is not to use montage and editing. Rather, it's to create the moment of truthfulness, in which the camera happens to just be there in time to register what's going on.

I didn't want to glorify or fetishize violence, I wanted to present it with the crudeness it has. The whole thing is trying to be truthful, so we went with a lot of references from documentaries. The explosions were like real-life explosions.

There's a tendency in movies to have spectacle explosions, with orange balls of fire. We also got experts who showed us the way people die. There aren't big stunt deaths inChildren of Men where the bullets riddle a character and make them crash through a window. It's more banal: people falling down.

We saw a lot more than documentaries, footage from the different fronts—we wanted to absorb the new technology into this idea of the future. We watched Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers made with the technology of that time [the late 1950s], with a camera that was relatively less portable. In our film, we have a camera with no weight at all; the cameraman, is running around with it and can leap behind a wall. Sheltered, he can stretch his arms to still have a view with the lens.

When we watch the news from say, Baghdad or northern Sri Lanka, it's usually five or seven seconds of this stuff. But the video cameras are actually on all the time. There's a lot of mobility, but you won't see that in the news—the camera that's going from niche to niche trying to find the right angle. They're in constant motion.

METRO: About the actors ...

CUARÓN: As well as his being the star of the movie, I consider Clive Owen a co-writer. I feel that way about Julianne Moore and Michael Caine, too, for the way they shaped their characters. I was just so lucky to witness these actors at work. Caine wanted to play his role as an older John Lennon ... he knew John Lennon, they were friends. The actors understood we were doing long shots. When you're doing that, the weight falls on the shoulders of the actors. You don't have the safety net later on to speed up the scene, or widen it or change performance—all the weight falls on the actors. If anything works in this movie it's because of these guys.

METRO: A last, silly question: did Salma Hayek ever see the diving board masturbation "Salmiiita!" scene in Y tu mamá también?

CUARÓN: She is my sister, Salmita! (laughs) I told her about this tribute to her before I filmed it. She was laughing: "it's a beautiful image!"

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

| D cont.

EF

G

H

I

J

KL

Pages in category "Dystopian novels"

The following 83 pages are in this category, out of 280 total. This list may not reflect recent changes (learn more).

(previous 200) (next 200) | OP

QR | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||