There is something about hearing Celia Johnson's internal monologue throughout all this that feels incredibly real, incredibly human, and incredibly unique to cinema. And then her acting – and those huge, emotion-filled eyes. There is no other film that has captured what this kind of experience is like, in all the pain, bittersweetness, impossibility and sense of fleeting chances; how the dreariness of a life can be flooded with meaning and color. Life is short; but don't have an affair, just watch Brief Encounter.

Brief Encounter

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Brief Encounter (play))

Product DetailsRailways on the Screen Hardcover – April 29, 1993

|

For other uses, see Brief Encounter (disambiguation).

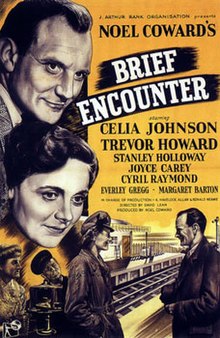

| Brief Encounter | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster

| |

| Directed by | David Lean |

| Produced by | Noël Coward Anthony Havelock-Allan Ronald Neame |

| Written by | Anthony Havelock-Allan David Lean Ronald Neame |

| Based on | Still Life 1936 play by Noël Coward |

| Starring | Celia Johnson Trevor Howard Stanley Holloway Joyce Carey Cyril Raymond Everley Gregg Margaret Barton |

| Music by | Sergei Rachmaninoff |

| Cinematography | Robert Krasker |

| Edited by | Jack Harris |

| Distributed by | Eagle-Lion Distributors(UK) Universal Pictures(US) |

Release dates

| 26 November 1945 (UK) |

Running time

| 86 minutes |

| Country | UK |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[1] |

Brief Encounter is a 1945 British romantic drama film directed by David Leanabout British suburban life, centring on Laura, a married woman with children, whose conventional life becomes increasingly complicated because of a chance meeting at a railway station with a stranger, Alec. They inadvertently but quickly progress to an emotional love affair, which brings about unexpected consequences.

The film stars Celia Johnson, Trevor Howard, Stanley Holloway and Joyce Carey. The screenplay is by Noël Coward, based on his 1936 one-act playStill Life. The soundtrack prominently features the Piano Concerto No. 2 bySergei Rachmaninoff, played by Eileen Joyce.

Contents

[hide]- 1Plot

- 2Cast

- 3Adaptation of Still Life

- 4Production notes

- 5Music

- 6Reception

- 7Adaptations of the film

- 8See also

- 9Notes

- 10References

- 11External links

Plot[edit]

In the latter months of 1938, Laura Jesson (Celia Johnson), a respectable middle-class British woman in an affectionate but rather dull marriage, tells her story while sitting at home with her husband, imagining that she is confessing her affair to him.Laura, like many women of her class at that time, goes to a nearby town every Thursday for shopping and to the cinema for a matinée. Returning from one such excursion to Milford, while waiting in the railway station's tea shop, she is helped by another passenger, who solicitously removes a piece of grit from her eye. The man is Alec Harvey (Trevor Howard), an idealistic doctor who also works one day a week as a consultant at the local hospital. Both are in their late thirties or early forties, married and with children. Enjoying each other's company, the two arrange to meet again. They are soon troubled to find their innocent and casual relationship quickly developing into something deeper.For a while, they meet openly, until they run into friends of Laura and the perceived need to lie arises. The second lie comes easier. They eventually go to a flat belonging to Stephen (Valentine Dyall), a friend of Alec's and a fellow doctor, but are interrupted by Stephen's unexpected and judgmental return. Laura, humiliated and ashamed, runs down the back stairs and into the streets. She walks for hours, sits on a bench and smokes, and is confronted by a police officer, with the implication that she could be perceived as a "streetwalker."The rather sordid turn of events brings home to the couple that both an affair and a future together are impossible. Realizing the danger and not wishing to hurt their families, they agree to part. Alec has been offered a job in Johannesburg, South Africa, where his brother lives.Their final meeting occurs in the railway station refreshment room, now seen for a second time with the poignant perspective of their story. As they await a heart-rending final parting, Dolly Messiter (Everley Gregg), a talkative acquaintance of Laura, invites herself to join them and begins chattering away, oblivious to the couple's inner misery.As they realize that they have been robbed of the chance for a final goodbye, Alec's train arrives. With Dolly still chattering, Alec departs with a last look at Laura but without the passionate farewell for which they both long. After shaking Messiter's hand, he discreetly squeezes Laura on the shoulder and leaves. Laura waits for a moment, anxiously hoping that Alec will walk back into the refreshment room, but he does not. As the train is heard pulling away, Laura is galvanized by emotion and, hearing an approaching express train, suddenly dashes out to the platform. The lights of the train flash across her face as she conquers a suicidal impulse. She then returns home to her family.Laura's kind and patient husband, Fred (Cyril Raymond), suddenly shows not only that he has noticed her distance in the past few weeks but that he has perhaps even guessed the reason. He thanks her for coming back to him. She cries in his embrace.

Enjoying each other's company, the two arrange to meet again. They are soon troubled to find their innocent and casual relationship quickly developing into something deeper.For a while, they meet openly, until they run into friends of Laura and the perceived need to lie arises. The second lie comes easier. They eventually go to a flat belonging to Stephen (Valentine Dyall), a friend of Alec's and a fellow doctor, but are interrupted by Stephen's unexpected and judgmental return. Laura, humiliated and ashamed, runs down the back stairs and into the streets. She walks for hours, sits on a bench and smokes, and is confronted by a police officer, with the implication that she could be perceived as a "streetwalker."The rather sordid turn of events brings home to the couple that both an affair and a future together are impossible. Realizing the danger and not wishing to hurt their families, they agree to part. Alec has been offered a job in Johannesburg, South Africa, where his brother lives.Their final meeting occurs in the railway station refreshment room, now seen for a second time with the poignant perspective of their story. As they await a heart-rending final parting, Dolly Messiter (Everley Gregg), a talkative acquaintance of Laura, invites herself to join them and begins chattering away, oblivious to the couple's inner misery.As they realize that they have been robbed of the chance for a final goodbye, Alec's train arrives. With Dolly still chattering, Alec departs with a last look at Laura but without the passionate farewell for which they both long. After shaking Messiter's hand, he discreetly squeezes Laura on the shoulder and leaves. Laura waits for a moment, anxiously hoping that Alec will walk back into the refreshment room, but he does not. As the train is heard pulling away, Laura is galvanized by emotion and, hearing an approaching express train, suddenly dashes out to the platform. The lights of the train flash across her face as she conquers a suicidal impulse. She then returns home to her family.Laura's kind and patient husband, Fred (Cyril Raymond), suddenly shows not only that he has noticed her distance in the past few weeks but that he has perhaps even guessed the reason. He thanks her for coming back to him. She cries in his embrace.Cast[edit]

- Celia Johnson as Laura Jesson

- Trevor Howard as Dr Alec Harvey

- Stanley Holloway as Albert Godby

- Joyce Carey as Myrtle Bagot

- Cyril Raymond as Fred Jesson

- Everley Gregg as Dolly Messiter

- Marjorie Mars as Mary Norton

- Margaret Barton as Beryl Walters, tea-room assistant

- Alfie Bass as the waiter at the Royal (uncredited)

- Wallace Bosco as the doctor at Bobbie's accident (uncredited)

- Sydney Bromley as Johnnie, second soldier (uncredited)

- Valentine Dyall as Stephen Lynn, Alec's friend (uncredited)

- Irene Handl as cellist and organist (uncredited)

Adaptation of Still Life[edit]The film is based on Noël Coward's one-act play Still Life (1936), one of ten short plays in the cycle Tonight at 8:30, designed for Gertrude Lawrence and Coward himself, and to be performed in various combinations as triple bills. All scenes in Still Life are set in the refreshment room of a railway station (the fictional Milford Junction).

As is common in films based on stage plays, the film depicts places only referred to in the play: Dr. Lynn's flat, Laura's home, a cinema, a restaurant and a branch of Boots the Chemist. In addition, a number of scenes have been added which are not in the play: a scene on a lake in a rowing boat where Dr. Harvey gets his feet wet; Laura wandering alone in the dark, sitting down on a park bench, smoking in public and being confronted by a police officer; and a drive in the country in a borrowed car.Some scenes are made less ambiguous and more dramatic in the film. The scene in which the two lovers are about to commit adultery is toned down: in the play it is left for the audience to decide whether they actually consummate their relationship; in the film it is intimated that they do not. In the film, Laura has only just arrived at Dr. Lynn's flat when the owner returns and is immediately led out by Dr. Harvey via the kitchen service door. Later, when Laura seems to want to throw herself in front of an express train, the film makes the intention clearer by means of voice-over narration. Also, in the play, the characters at the Milford station—Mrs. Baggot, Mr. Godby, Beryl, and Stanley—are very much aware of the growing relationship between Laura and Alec and sometimes mention it in an offhand manner, whereas in the film, they barely take any notice of them or what they are doing, either showing them respect for their privacy or just being oblivious. The final scene of the film showing Laura embracing her husband after he shows that he has noticed her distance in the past few weeks and perhaps even guessed the reason is not in the original Coward play.There are two editions of Coward's original screenplay for the film adaptation, both listed in the bibliography.In her book Noël Coward (1987), Frances Gray says that Brief Encounter is, after the major comedies, the one work of Coward that almost everybody knows and has probably seen; it has featured frequently on television and its viewing figures are invariably high.Gray acknowledges a common criticism of the play: why do the characters not consummate the affair? Gray argues that their problem is class consciousness: the working classes can act in a vulgar way, and the upper class can be silly; but the middle class is, or at least considers itself, the moral backbone of society – a notion whose validity Coward did not really want to question or jeopardise, as the middle classes were Coward's principal audience.

However, Laura in her narration stresses that what holds her back is her horror at the thought of betraying her husband and her settled moral values, tempted though she is by the force of a love affair. Indeed, it is this very tension which has made the film such an enduring favourite.The values which Laura precariously, but ultimately successfully, clings to were widely shared and respected (if not always observed) at the time of the film's original setting (the status of a divorced woman, for example, remained sufficiently scandalous in the UK to cause Edward VIII to abdicate in 1936). Updating the story may have left those values behind and with them vanished the credibility of the plot, which may be why the 1974 remake could not compete.[6]The film is widely admired for the beauty of its black-and-white photography and the atmosphere created by the steam-age railway setting, both of which were particular to the original David Lean version.Handford, Peter (1980). Sounds of Railways. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7631-4.7]The film was a great success in the UK and such a hit in the US that Celia Johnson was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress.The film was released amid the social and cultural context of the Second World War when 'brief encounters' were thought to be commonplace and women had far greater sexual and economic freedom than previously. In British National Cinema(1997), Sarah Street argues that "Brief Encounter thus articulated a range of feelings about infidelity which invited easy identification, whether it involved one's husband, lover, children or country" (p. 55). In this context, feminist critics read the film as an attempt at stabilising relationships to return to the status quo.[citation needed] Meanwhile, in his 1993 BFI book on the film, Richard Dyer notes that owing to the rise of homosexual law reform, gay men also viewed the plight of the characters as comparable to their own social constraint in the formation and maintenance of relationships. Sean O'Connor considers the film to be an "allegorical representation of forbidden love" informed by Noël Coward's experiences as a closeted homosexual.[8]The British play and film The History Boys features two of the main characters reciting a passage of the film. (The scene portrayed, with Posner playing Celia Johnson and Scripps as Cyril Raymond, is in the closing minutes of the film where Laura begins, "I really meant to do it.")Kathryn Altman, wife of director Robert Altman said, "One day, years and years ago, just after the war, [Altman] had nothing to do and he went to a theater in the middle of the afternoon to see a movie. Not a Hollywood movie: a British movie. He said the main character was not glamorous, not a babe. And at first he wondered why he was even watching it. But twenty minutes later he was in tears, and had fallen in love with her. And it made him feel that it wasn't just a movie." The film wasBrief Encounter. [9]Adaptations of the film[edit]

Radio[edit]

Brief Encounter was adapted as a radio play on 20 November 1946 episode ofAcademy Award Theater, starring Greer Garson.[11] It was presented three times onThe Screen Guild Theater, first on 12 May 1947 episode with Herbert Marshall andLilli Palmer, again on 12 January 1948 with Herbert Marshall and Irene Dunne and finally on 11 January 1951 with Stewart Granger and Deborah Kerr. It was also adapted to Lux Radio Theater on 29 November 1948 episode with Van Heflin and Greer Garson and on 14 May 1951 episode with Olivia de Havilland and Richard Basehart.See also[edit]

- Same Time, Next Year a 1978 film

- Falling in Love a 1984 film

- Banbury Cakes

- BFI Top 100 British films

- Staying On (1980) co-starring Celia Johnson & Trevor Howard

Notes[edit]

- ^ "US Life or Death to Brit Pix", Variety 25 Dec 1946 p 9

- ^ "BBC - Cumbria - Cumbria 0n Film - Brief Encounter".bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Whitaker, Brian (comp.) (1990). Notes & Queries. Fourth Estate. ISBN 1-872180-22-1.

- ^ Robert Murphy, Realism and Tinsel: Cinema and Society in Britain 1939-48 2003 p209

- ^ "Brief Encounter". rottentomatoes.com. 26 November 1945. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Handford, Peter (1980). Sounds of Railways. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7631-4.

- ^ Huntley, John (1993). Railways on the Screen. Ian Allan.ISBN 0-7110-2059-0.

- ^ O'Connor, p. 157

- ^ A quote from the final scene in the 2014 documentaryAltman.

- ^ "TV - 'Brief Encounter' - Burton and Miss Loren Portray Lovers on Hallmark Film at 8 - 30 on NBC - Article - NYTimes.com". nytimes.com. 12 November 1974. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Greer Garson Stars in "Brief Encounter" On Academy Award--WHP". Harrisburg Telegraph. November 16, 1946. p. 17. Retrieved September 14, 2015 – viaNewspapers.com.

- ^ Billington, Michael (18 February 2008). "Theatre Review: Brief Encounter". The Guardian (London). Retrieved26 April 2010.

- ^ Cheal, David (8 February 2008). "Brief Encounter: 'I want people to laugh and cry. That's our job'". The Daily Telegraph (London).

- ^ Kneehigh Theatre tour dates Archived 22 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Noel Coward's Brief Encounter to Open at Studio 54 in September BroadwayWorld.com Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth. "Broadway's 'Brief Encounter', a Romance With Theatrical Lift, Ends Jan. 2" playbill.com, 2 January 2011

- ^ Kneehigh Tour Dates [1] Retrieved October 2013.

- ^ Houston Grand Opera performance page Archived 30 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

August 28, 2015

03:01 PM