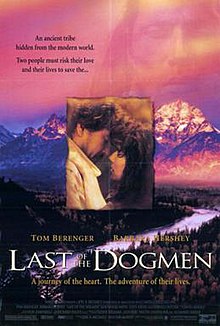

Theatrical release poster

Directed by Tab Murphy Produced by Joel B. Michaels Written by Tab Murphy Starring

Narrated by Wilford Brimley Music by David Arnold Cinematography Karl Walter Lindenlaub Edited by Richard Halsey

Production

company

Distributed by

- Savoy Pictures

- Pathé (International)

Release dates

- September 8, 1995 (USA)

Running time

118 minutes Country United States Language English Box office $7,024,389[1]

Theatrical release poster

Production

company

company

- Savoy Pictures

- Pathé (International)

Release dates

- September 8, 1995 (USA)

Running time

Dog Soldiers

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about Cheyenne warrior society. For other uses, see Dog Soldiers (disambiguation).

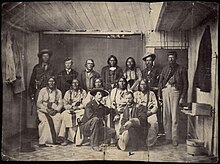

The Dog Soldiers or Dog Men (Cheyenne Hotamétaneo'o) was one of sixmilitary societies of the Cheyenne Indians. Beginning in the late 1830s, this society evolved into a separate, militaristic band that played a dominant role in Cheyenne resistance to American expansion in Kansas, Nebraska, Coloradoand Wyoming, where the Cheyenne had settled in the early 19th Century.

After the deaths of nearly half the Southern Cheyenne in the cholera epidemicof 1849, many of the remaining Masikota band joined the Dog Soldiers. It effectively became a separate band, occupying territory between the Northern and Southern Cheyenne. Its members often opposed policies of peace chiefs such as Black Kettle. In 1869, most of the band were killed by United States Army forces in the Battle of Summit Springs.

In the 21st-century, there are reports of the revival of the Dog Soldiers society in such areas as the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana and among the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about Cheyenne warrior society. For other uses, see Dog Soldiers (disambiguation).

The Dog Soldiers or Dog Men (Cheyenne Hotamétaneo'o) was one of sixmilitary societies of the Cheyenne Indians. Beginning in the late 1830s, this society evolved into a separate, militaristic band that played a dominant role in Cheyenne resistance to American expansion in Kansas, Nebraska, Coloradoand Wyoming, where the Cheyenne had settled in the early 19th Century.

After the deaths of nearly half the Southern Cheyenne in the cholera epidemicof 1849, many of the remaining Masikota band joined the Dog Soldiers. It effectively became a separate band, occupying territory between the Northern and Southern Cheyenne. Its members often opposed policies of peace chiefs such as Black Kettle. In 1869, most of the band were killed by United States Army forces in the Battle of Summit Springs.

In the 21st-century, there are reports of the revival of the Dog Soldiers society in such areas as the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana and among the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma.

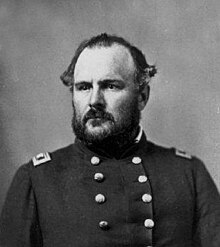

Indian wars[edit]

In the late 1860s, the Dog Soldiers were crucial in Cheyenne resistance to American expansion. Dog Soldiers refused to sign treaties that limited their hunting grounds and restricted them to a reservation south of the Arkansas River. They attempted to hold their traditional lands at Smoky Hill, but the campaigns of General Philip Sheridan foiled these efforts. After the Battle of Beecher's Island, many Dog Soldiers were forced to retreat south of the Arkansas River.

In the spring of 1867 they returned north with the intention of joining Red Cloud and his Oglala band in Powder River. Attacked by General Eugene Carr, the Dog Soldiers began raiding settlements on Smoky Hill River in revenge. Eventually, Chief Tall Bull led them west into Colorado. After raiding sites in Kansas, they were attacked by a force composed ofPawnee Scouts led by Major Frank North, and United States cavalry, who killed nearly all the band, including Tall Bull, in theBattle of Summit Springs in June 1869.

In the late 1860s, the Dog Soldiers were crucial in Cheyenne resistance to American expansion. Dog Soldiers refused to sign treaties that limited their hunting grounds and restricted them to a reservation south of the Arkansas River. They attempted to hold their traditional lands at Smoky Hill, but the campaigns of General Philip Sheridan foiled these efforts. After the Battle of Beecher's Island, many Dog Soldiers were forced to retreat south of the Arkansas River.

In the spring of 1867 they returned north with the intention of joining Red Cloud and his Oglala band in Powder River. Attacked by General Eugene Carr, the Dog Soldiers began raiding settlements on Smoky Hill River in revenge. Eventually, Chief Tall Bull led them west into Colorado. After raiding sites in Kansas, they were attacked by a force composed ofPawnee Scouts led by Major Frank North, and United States cavalry, who killed nearly all the band, including Tall Bull, in theBattle of Summit Springs in June 1869.

Films[edit]

The massacre has been portrayed in several western movies, including Tomahawk (1951); The Guns of Fort Petticoat(1957); Soldier Blue (1970); The Last Warrior (1970); Little Big Man (1970); Young Guns (1988); Last of the Dogmen(1995); and The Last Samurai (2003).

Literature[edit]

The event has also been written about in such works of literature as The Massacre at Sand Creek (1995) by Bruce Cutler; A Very Small Remnant (1963) by Michael Straight; Centennial (1974) by James Michener; From Sand Creek (1981) by Simon Ortiz; James Bradley's Flyboys: A True Story of Courage (2003); and Lauren Small's Choke Creek (2009).

Hoig, Stan (2005) [1974]. The Sand Creek Massacre. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8061-1147-6

Attack[edit]

Black Kettle, leading chief of around 800 mostly Southern Cheyenne, had led his band, joined by some Arapahos under Chief Niwot, to Fort Lyon in compliance with provisions of a peace parley held in Denver in September 1864.[19] After a while, the Native Americans were requested to relocate to Big Sandy Creek, less than 40 miles northwest of Fort Lyon, with the guarantee of "perfect safety" remaining in effect.[20]The Dog Soldiers, who had been responsible for many of the attacks and raids on whites, were not part of this encampment.

Unwilling to to surrender themselves to military authority most of the tribal warriors refused the offer of protection, leaving only about 75 men, plus all the women and children in the village. The men who remained were mostly too old or too young to hunt. Black Kettle flew an American flag, with a white flag tied beneath it,[20] over his lodge, as the Fort Lyon commander had advised him. This was to show he was friendly and forestall any attack by the Colorado soldiers.[21]

Meanwhile, Chivington and 425 men of the 3rd Colorado Cavalry rode to Fort Lyon arriving on November 28th 1864. Once at the Fort Chivington took command of 250 men of the 1st Colorado Cavalry and maybe as many as 12 men of the 1st Regiment New Mexico Volunteer Infantry then set out for Black Kettle's encampment. James Beckwourth, noted frontiersman, acted as guide for Chivington.[22] The following morning, Chivington gave the order to attack. Two officers, Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer, commanding Company D and Company K of the First Colorado Cavalry, refused to obey and told their men to hold fire.[23]

However, the rest of Chivington's men immediately attacked the village. Ignoring the American flag and a white flag that was run up shortly after the attack began, they murdered as many of the Indians as they could.

The natives, lacking artillery, could not make much resistance. Some of the natives cut horses from the camp's herd and fled up Sand Creek or to a nearby Cheyenne camp on the headwaters of the Smoky Hill River. Others, including trader George Bent, fled upstream and dug holes in the sand beneath the banks of the stream. They were pursued by the troops and fired on, but many survived.[28] Cheyenne warrior Morning Star said that most of the Indian dead were killed by cannon fire, especially those firing from the south bank of the river at the people retreating up the creek.[29]

In testimony before a Congressional committee investigating the massacre, Chivington claimed that as many as 500–600 Indian warriors were killed.[30] Historian Alan Brinkley wrote that 133 Indians were killed, 105 of whom were women and children.[31] White eye-witness John S. Smith reported that 70–80 Indians were killed, including 20–30 warriors,[2] which agrees with Brinkley's figure as to the number of men killed. George Bent, the son of the American William Bent and a Cheyenne mother, who was in the village when the attack came and was wounded by the soldiers, gave two different accounts of the natives' loss. On March 15, 1889, he wrote to Samuel F. Tappan that 137 people were killed: 28 men and 109 women and children.[32] However, on April 30, 1913, when he was very old, he wrote that "about 53 men" and "110 women and children" were killed and many people wounded.[33] Bent's first figures are in close accord with those of Brinkley and agree with Smith as to the number of men who were killed.

Although initial reports indicated 10 soldiers killed and 38 wounded, the final tally was 4 killed and 21 wounded in the 1st Colorado Cavalry and 20 killed or mortally wounded and 31 other wounded in the 3rd Colorado Cavalry; adding up to 24 killed and 52 wounded.[2] Dee Brown wrote that some of Chivington's men were drunk and that many of the soldiers' casualties were due to friendly fire[34] but neither of these claims is supported by Gregory F. Michno[35] or Stan Hoig[36] in their books devoted to the massacre.

Before Chivington and his men left the area, they plundered the tipis and took the horses. After the smoke cleared, Chivington's men came back and killed many of the wounded. They also scalped many of the dead, regardless of whether they were women, children or infants. Chivington and his men dressed their weapons, hats and gear with scalps and other body parts, including human fetuses and male and female genitalia.[37] They also publicly displayed these battle trophies inDenver's Apollo Theater and area saloons. Three Indians who remained in the village are known to have survived the massacre: George Bent's brother Charlie Bent, and two Cheyenne women who were later turned over to William Bent.[38]

Aftermath[edit]

The Sand Creek Massacre resulted in a heavy loss of life, mostly among Cheyenne and Arapaho women and children. Hardest hit by the massacre were the Wutapai, Black Kettle's band. Perhaps half of the Hevhaitaniu were lost, including the chiefs Yellow Wolf and Big Man. The Oivimana, led by War Bonnet, lost about half their number. There were heavy losses to the Hisiometanio (Ridge Men) under White Antelope. Chief One Eye was also killed, along with many of his band. The Suhtai clan and the Heviqxnipahis clan under chief Sand Hill experienced relatively few losses. The Dog Soldiers and the Masikota, who by that time had allied, were not present at Sand Creek.[39] Of about ten lodges of Arapaho under Chief Left Hand, representing about fifty or sixty people, only a handful escaped with their lives.[40]

After hiding all day above the camp, in holes dug beneath the bank of Sand Creek, the survivors there, many of whom were wounded, moved up the stream and spent the night on the prairie. Trips were made to the site of the camp but very few survivors were found there. After a cold night without shelter, the survivors set out toward the Cheyenne camp on the headwaters of the Smoky Hill River. They soon met up with other survivors who had escaped with part of the horse herd, some returning from the Smoky Hill camp where they had fled during the attack. They then proceeded to the camp, where they received assistance.[41]

The massacre disrupted the traditional Cheyenne power structure, because of the deaths of eight members of the Council of Forty-Four. White Antelope, One Eye, Yellow Wolf, Big Man, Bear Man, War Bonnet, Spotted Crow, and Bear Robe were all killed, as were the headmen of some of the Cheyenne military societies.[42] Among the chiefs killed were most of those who had advocated peace with white settlers and the U.S. government.[43] The net effect of the murders and ensuing weakening of the peace faction exacerbated the developing social and political rift. Traditional council chiefs, mature men who sought consensus and looked to the future of their people, and their followers, were opposed by the younger and more militaristic Dog Soldiers.Beginning in the 1830s, the Dog Soldiers had evolved from a Cheyenne military society of that name into a separate band of Cheyenne and Lakota warriors. They took as their territory the area around the headwaters of the Republican and Smoky Hill rivers in southern Nebraska, northern Kansas, and the northeastern Colorado Territory. By the 1860s, as conflict between Indians and encroaching whites intensified, the Dog Soldiers and military societies within other Cheyenne bands countered the influence of the traditional Council of Forty-Four chiefs who, as more mature men, took a larger view and were more likely to favor peace with the whites.[44] To the Dog Soldiers, the Sand Creek massacre illustrated the folly of the peace chiefs' policy of accommodating the whites through treaties such as the first Treaty of Fort Laramie and the Treaty of Fort Wise.[6] They believed their militant position toward the whites was justified by the massacre.[44]

The events at Sand Creek dealt a fatal blow to the traditional Cheyenne clan system and the authority of its Council of Chiefs. It had already been weakened by the numerous deaths due to the 1849 cholera epidemic, which killed perhaps half the Southern Cheyenne population, especially the Masikota and Oktoguna bands.[45] It was further weakened by the emergence of the separate Dog Soldiers band.[46]

Retaliation[edit]

After the brutal slaughter of those who supported peace, many of the Cheyenne, including the great warrior Roman Nose, and many Arapaho joined the Dog Soldiers. They sought revenge on settlers throughout the Platte valley, including an 1865 attack on what became Fort Caspar, Wyoming.

Following the massacre, the survivors reached the camps of the Cheyenne on the Smokey Hill and Republican rivers. The war pipe was smoked and passed from camp to camp among the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors in the area. In January 1865, they planned and carried out an attack with 1,000 warriors on the stage station and fort, then called Camp Rankin, at present-day Julesburg, Colorado. This was followed by numerous raids along the South Platte both east and west of Julesburg, and a second raid on the town of Julesburg in early February. The associated bands captured much loot and killed many white settlers, including women and children. The bulk of the Indians then moved north into Nebraska on their way to the Black Hills and the Powder River Country.[47]

Black Kettle continued to speak for peace and did not join in the second raid or in the journey to the Powder River country. He left the camp and returned with 80 lodges to the Arkansas River to seek peace with the Coloradoans.[48]

Official investigations[edit]

Initially, the Sand Creek engagement was reported as a victory against a brave and numerous foe. Within weeks, however, witnesses and survivors began telling stories of a possible massacre. Several investigations were conducted – two by the military, and one by the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. The panel declared:[49]

In conclusion, your committee are of the opinion that for the purpose of vindicating the cause of justice and upholding the honor of the nation, prompt and energetic measures should be at once taken to remove from office those who have thus disgraced the government by whom they are employed, and to punish, as their crimes deserve, those who have been guilty of these brutal and cowardly acts.

Depiction in fiction[edit]Statements taken by Major Edward W. Wynkoop and his adjutant substantiated the later accounts of survivors. These statements were filed with his reports and can be found in the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, copies of which were submitted as evidence in the Joint Committee of the Conduct of the War and in separate hearings conducted by the military in Denver. Lieutenant James D. Cannon describes the mutilation of human genitalia by the soldiers, "men, women, and children's privates cut out. I heard one man say that he had cut a woman's private parts out and had them for exhibition on a stick. I heard of one instance of a child, a few months old, being thrown into the feed-box of a wagon, and after being carried some distance, left on the ground to perish; I also heard of numerous instances in which men had cut out the private parts of females and stretched them over their saddle-bows, and some of them over their hats."[50]

During these investigations, numerous witnesses came forward with damning testimony, almost all of which was corroborated by other witnesses. One witness, Captain Silas Soule, who had ordered the men under his command not to fire their weapons, was murdered in Denver just weeks after offering his testimony. However, despite the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the Wars' recommendation, no charges were brought against those who committed the massacre-Chivington was beyond the reach of army justice because he'd already resigned his commission. The closest thing to a punishment he suffered was the effective end of his political aspirations.Calhoun, Patricia (March 27, 2013). "Sand Creek Massacre and John Chivington's explosive actions 151 years after Glorieta Pass". Westword. RetrievedMay 28, 2013.

In his autobiographical Memories of a Lifetime in the Pike's Peak Region, Irving Howbert, an 18-year-old cavalryman who was later one of the founders of Colorado Springs, defended Chivington, having claimed instead that the Indian women and children were not attacked, though a few who did not leave the camp were killed once the fighting began. He insisted that the number of warriors in the village was equal to the force of the Colorado cavalry. Chivington, claimed Howbert, was retaliating for Indian attacks on wagon trains and settlements in Colorado and for the torture and the killings of citizens during the preceding three years. Howbert said the evidence of the previous Indian attacks on the settlers was shown by their confiscation of "more than a dozen scalps of white people, some of them from the heads of women and children."[51]Howbert claimed that the account of the battle to the United States Congress made by Lieutenant Col. Samuel F. Tappan was inaccurate, accusing Tappan of giving a false view of the battle because Tappan and Chivington had been military rivals.[51]

A monument installed on the Colorado State Capitol grounds in 1909 lists Sand Creek as one of the "battles and engagements" fought by Colorado troops in the American Civil War. In 2002, the Colorado Historical Society (now History Colorado), authorized by the Colorado General Assembly, added an additional plaque to the monument, which states that the original designers of the monument "mischaracterized" Sand Creek by calling it a battle.[52]

Films[edit]

The massacre has been portrayed in several western movies, including Tomahawk (1951); The Guns of Fort Petticoat(1957); Soldier Blue (1970); The Last Warrior (1970); Little Big Man (1970); Young Guns (1988); Last of the Dogmen(1995); and The Last Samurai (2003)

Film[edit]

Last of the Dogmen (1995) is a fictional film about the search for and discovery of an unknown band of Dog Soldiers from a tribe of Cheyenne Indians who escaped the 1864 Sand Creek massacre and survived for more than a hundred years secluded in the Montana wilderness.

Last of the Dogmen (1995) is a fictional film about the search for and discovery of an unknown band of Dog Soldiers from a tribe of Cheyenne Indians who escaped the 1864 Sand Creek massacre and survived for more than a hundred years secluded in the Montana wilderness.

Literature[edit]

The Dog Soldiers are prominently mentioned in John Locke's Emmett Love series of novels.[18]

The Dog Soldiers are prominently mentioned in John Locke's Emmett Love series of novels.[18]

Television[edit]

The AMC series Hell on Wheels features a band of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers in the first season of the series. They fight back against the railroad men who are building of the first segment of the Union Pacific Railroad through Cheyenne territory. Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman features Cheyenne Dog Soldiers throughout the series.

The AMC series Hell on Wheels features a band of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers in the first season of the series. They fight back against the railroad men who are building of the first segment of the Union Pacific Railroad through Cheyenne territory. Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman features Cheyenne Dog Soldiers throughout the series.

Bibliography[edit]

- Broome, Jeff Dog Soldier Justice: The Ordeal of Susanna Alderdice in the Kansas Indian War, Lincoln, Kansas: Lincoln County Historical Society, 2003. ISBN 0-9742546-1-4

- Brown, Dee. (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-6669-1.

- Greene, Jerome A. (2004). Washita, The Southern Cheyenne and the U.S. Army, Campaigns and Commanders Series, vol. 3. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3551-4.

- Hoig, Stan. (1980). The Peace Chiefs of the Cheyennes, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1573-4.

- Hyde, George E. (1968). Life of George Bent Written from His Letters. Ed. by Savoie Lottinville, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1577-7.

- Cozzens, Peter, "Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars: 1865-1890: Vol.3, Conquering the Southern Plains," ISBN 0-8117-0019-4

- Broome, Jeff Dog Soldier Justice: The Ordeal of Susanna Alderdice in the Kansas Indian War, Lincoln, Kansas: Lincoln County Historical Society, 2003. ISBN 0-9742546-1-4

- Brown, Dee. (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-6669-1.

- Greene, Jerome A. (2004). Washita, The Southern Cheyenne and the U.S. Army, Campaigns and Commanders Series, vol. 3. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3551-4.

- Hoig, Stan. (1980). The Peace Chiefs of the Cheyennes, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1573-4.

- Hyde, George E. (1968). Life of George Bent Written from His Letters. Ed. by Savoie Lottinville, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1577-7.

- Cozzens, Peter, "Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars: 1865-1890: Vol.3, Conquering the Southern Plains," ISBN 0-8117-0019-4

See also[edit]

Brief Synopsis

Cast[edit]

- Tom Berenger as Lewis Gates

- Barbara Hershey as Prof. Lillian Diane ("L.D.") Sloan

- Kurtwood Smith as Sheriff Deegan

- Steve Reevis as Yellow Wolf

- Andrew Miller as Briggs

- Gregory Scott Cummins as Sears

- Mark Boone Junior as Tattoo

- Helen Calahasen as Yellow Wolf's wife

- Eugene Blackbear as Spotted Elk

- Dawn Lavand as Indian Girl

- Sidel Standing Elk as Lean Bear

- Hunter Bodine as Kid

- Graham Jarvis as Pharmacist

- Marvin R. Thunderbull as Wolfscout

- Parley Baer as Mr. Hollis

- Sherwood Price as Tracker

- Molly Parker as Nurse

- Antony Holland as Doc Carvey

- Robert Donley as Old Timer

- Brian Stollery as Grad Student

- Mitchell LaPlante as Wild Boy

- Wilford Brimley as The Narrator

- Zip as Zip[2]

- Tom Berenger as Lewis Gates

- Barbara Hershey as Prof. Lillian Diane ("L.D.") Sloan

- Kurtwood Smith as Sheriff Deegan

- Steve Reevis as Yellow Wolf

- Andrew Miller as Briggs

- Gregory Scott Cummins as Sears

- Mark Boone Junior as Tattoo

- Helen Calahasen as Yellow Wolf's wife

- Eugene Blackbear as Spotted Elk

- Dawn Lavand as Indian Girl

- Sidel Standing Elk as Lean Bear

- Hunter Bodine as Kid

- Graham Jarvis as Pharmacist

- Marvin R. Thunderbull as Wolfscout

- Parley Baer as Mr. Hollis

- Sherwood Price as Tracker

- Molly Parker as Nurse

- Antony Holland as Doc Carvey

- Robert Donley as Old Timer

- Brian Stollery as Grad Student

- Mitchell LaPlante as Wild Boy

- Wilford Brimley as The Narrator

- Zip as Zip[2]

Production[edit]

Plot[edit]

Distraught but skillful bounty hunter Lewis Gates (Tom Berenger), accompanied by his horse and faithful companion Zip (an Australian cattle dog), tracks three armed escaped convicts into Montana's Oxbow Quadrangle, at the persistence of his unforgiving father-in-law, who blames Gates for his daughter's tragic death. Gates sees the convicts but hears shots. Investigating the scene, all Gates finds is a bloody scrap of cloth, "enough blood to paint [the sheriff's office", a bloody rifle shell, and an old-fashioned Indian arrow.

Gates takes the arrow to archaeologist Lillian Sloan (Barbara Hershey), who identifies it as a replica of the arrows used by Cheyenne Dog Soldiers. Gates doesn't think it's a replica and, after some library research, develops a long list of people who have disappeared into the Oxbow. He also finds a story of a "wild child" captured in the woods in the early 20th century. Now, he's convinced that the fugitives were killed by a tribe of Dog Soldiers, a hardy band of Native Americans who somehow escaped the 1864 Sand Creek massacre and survived for 128 years, secluded in the Montana Wilderness, killing anyone who threatened to find and expose them.

Gates convinces Sloan to join him in a search for the band. The two enter the Oxbow and begin to search. They survive many mishaps and bond throughout their journey, eventually venturing deeper into the wilderness than Gates has ever gone before, around 50 miles in.

Nearing the end of their supplies, Sloan suggests heading back. As the two are packing their gear, they are suddenly attacked by Cheyenne Indians. Sloan, speaking the Cheyenne language, deescalates the situation, and the two are taken captive by Yellow Wolf (Steve Reevis). Taken to the Cheyenne encampment hidden behind a waterfall, the duo meet the village leader Spotted Elk (Eugene Blackbear), who tells them of the escape and salvation of the Cheyenne 128 years ago, as well as his own run-in with the "white people" when he was a child.

Gates and Sloan slowly become friendly with the Cheyenne. However, Yellow Wolf's son is sick, wounded after the gunfight with the convicts. Despite the elder's concerns, Sloan convinces Yellow Wolf to allow Gates to ride into town to obtain medicine. In town, Gates robs the pharmacy and is chased by local law enforcement, including Sheriff Deegan, his father-in-law (Kurtwood Smith).

After escaping, Gates meets Yellow Wolf in the wilderness, and they return to the Cheyenne camp. By this time, the sheriff has gathered a posse and sets out to hunt down Gates both for robbing the store and to find Gates' female companion, whom the sheriff believes Gates has hiding in the Oxbow.

Gates and Sloan continue to grow closer to the Cheyenne, and Sloan discloses that they are indeed the last of their kind. However, Yellow Wolf shows Gates that the sheriff is following his trail and is slowly getting closer to the encampment. Knowing that if discovered, the Cheyenne will fight and die, Gates proposes a solution; using some leftover TNT the Cheyenne had taken from explorers many years earlier, he'll create a distraction and allow the Cheyenne to flee deeper inside the Oxbow and live in peace, far away from civilization. Sloan decides to stay with the Cheyenne, which Gates reluctantly agrees to.

The two share a passionate kiss, and Gates begins to set up his plan. Gates gives himself up to the sheriff and pleads with him to leave the wilderness. However, the sheriff discovers the hidden tunnel and prepares to enter it. Escaping, Gates attempts to light the TNT with a rifle, but the sheriff stops him and threatens him with a gun to his head. Yellow Wolf appears, surprising the sheriff, and fires an arrow at the TNT, setting it off.

Gates and the sheriff are propelled out of the tunnel into the waterfall. Gates saves the sheriff, who is badly wounded. The deputy tells everyone to clear out, and they all head back to town to treat the wounded sheriff and Gates.

In Gates' holding cell, the sheriff confronts him about what Gates saw. Gates relents and says some things don't need an explanation; they deserve to remain undiscovered. This seemingly helps smooth over Gates' and the sheriff's relationship.

Sloan and the Cheyenne are shown to have successfully escaped. An indeterminate time later, Gates has begun searching for them. Using hints provided by Sloan, he is able to find them. The film ends with a passionate embrace between Sloan and Gates.