More civilians died in the siege of Leningrad than in the modernist infernos of Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, taken together.

Preparations[edit]

German plans[edit]

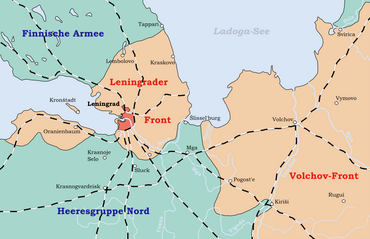

Army Group North under Feldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb advanced to Leningrad, its primary objective. Von Leeb's plan called for capturing the city on the move, but due to Hitler's recall of 4th Panzer Group (persuaded by his Chief of General Staff, Franz Halder, to transfer this south to participate in Fedor von Bock's push for Moscow),[19] von Leeb had to lay the city under siege indefinitely after reaching the shores of Lake Ladoga, while trying to complete the encirclement and reaching the Finnish Army under Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim waiting at the Svir River, east of Leningrad.[20]

Finnish military forces were located north of Leningrad, while German forces occupied territories to the south.[21] Both German and Finnish forces had the goal of encircling Leningrad and maintaining the blockade perimeter, thus cutting off all communication with the city and preventing the defenders from receiving any supplies — although Finnish participation in the blockade mainly consisted of recapture of lands lost in the Winter War. The Germans planned on lack of food being their chief weapon against the citizens; German scientists had calculated that the city would reach starvation after only a few weeks.[1][2][20][22][23][24]

Leningrad fortified region[edit]

On 27 June 1941, the Council of Deputies of the Leningrad administration organised "First response groups" of civilians. In the next days the entire civilian population of Leningrad was informed of the danger and over a million citizens were mobilised for the construction of fortifications. Several lines of defences were built along the perimeter of the city in order to repulse hostile forces approaching from north and south by means of civilian resistance.[2][4]

In the south one of the fortified lines ran from the mouth of the Luga River toChudovo, Gatchina, Uritsk, Pulkovo and then through the Neva River. Another line of defence passed through Peterhof to Gatchina, Pulkovo, Kolpino and Koltushy. In the north the defensive line against the Finns, the Karelian Fortified Region, had been maintained in the northern suburbs of Leningrad since the 1930s, and was now returned to service. A total of 306 km (190 mi) of timber barricades, 635 km (395 mi) of wire entanglements, 700 km (430 mi) of anti-tank ditches, 5,000 earth-and-timber emplacements and reinforced concrete weapon emplacements and 25,000 km (16,000 mi)[25] of open trenches were constructed or excavated by civilians. Even the guns from the cruiserAurora were moved inland to the Pulkovo Heights to the south of Leningrad.

Siege of Leningrad

Establishment[edit]

The 4th Panzer Group from East Prussia took Pskov following a swift advance and managed to reach Novgorod by 16 August. The Soviet defenders fought to the death, despite the German discovery of the Soviet defence plans on an officer’s corpse. After the capture of Novgorod, General Hoepner’s 4th Panzer Group continued its progress towards Leningrad.[26]However, the 18th Army — despite some 350,000 men lagging behind — forced its way to Ostrov and Pskov after the Soviet troops of the Northwestern Front retreated towards Leningrad. On 10 July, both Ostrov and Pskov were captured and the18th Army reached Narva and Kingisepp, from where advance toward Leningrad continued from the Luga River line. This had the effect of creating siege positions from the Gulf of Finland to Lake Ladoga, with the eventual aim of isolating Leningrad from all directions. The Finnish Army was then expected to advance along the eastern shore of Lake Ladoga.[27]

Severing lines of communication[edit]

On 6 August, Hitler repeated his order: "Leningrad first, Donetsk Basin second, Moscow third."[32] From August 1941 until January 1944, anything that happened between the Arctic Ocean and Lake Ilmen concerned the Wehrmacht's Leningrad siege operations.[4] Arctic convoys using the Northern Sea Route delivered American Lend-Lease and British food and war materiel supplies to the Murmansk railhead (although the rail link to Leningrad was cut off by Finnish armies just north of the city), as well as several other locations in Lapland.[citation needed]

Encirclement of Leningrad[edit]

Finnish intelligence had broken some of the Soviet military codes and were able to read their low-level communications. This was particularly helpful for Hitler, who constantly requested intelligence information about Leningrad.[4][33]Finland's role in Operation Barbarossa was laid out in Hitler's Directive 21, "The mass of the Finnish army will have the task, in accordance with the advance made by the northern wing of the German armies, of tying up maximum Russian (sic - Soviet) strength by attacking to the west, or on both sides, of Lake Ladoga".[34] The last rail connection to Leningrad was severed on 30 August, when the Germans reached the Neva River. On 8 September, the road to the besieged city was severed when the Germans reached Lake Ladoga at Shlisselburg, leaving just a corridor of land between Lake Ladoga and Leningrad which remained unoccupied by Axis forces. Bombing on 8 September caused 178 fires.[35]

On 21 September, German High Command considered the options of how to destroy Leningrad. Simply occupying the city was ruled out "because it would make us responsible for food supply".[36] The resolution was to lay the city under siege and bombardment, starving its population. "Early next year we enter the city (if the Finns do it first we do not object), lead those still alive into inner Russia or into captivity, wipe Leningrad from the face of the earth through demolitions, and hand the area north of the Neva to the Finns."[37] On 7 October, Hitler sent a further directive signed by Alfred Jodl reminding Army Group North not to accept capitulation.[38]

Defence of civilian evacuees[edit]

According to Zhukov, "Before the war Leningrad had a population of 3,103,000 and 3,385,000 counting the suburbs. As many as 1,743,129, including 414,148 children were evacuated" between 29 June 1941 and 31 March 1943. They were moved to the Volga area, the Urals, Siberia and Kazakhstan.[31]:439

By September 1941, the link with the Volkhov Front (commanded by Kirill Meretskov) was severed and the defensive sectors were held by four armies: 23rd Army in the northern sector, 42nd Army on the western sector, 55th Army on the southern sector, and the 67th Army on the eastern sector. The 8th Army of the Volkhov Front had the responsibility of maintaining the logistic route to the city in coordination with the Ladoga Flotilla. Air cover for the city was provided by the Leningrad military district PVO Corps and Baltic Fleet naval aviation units.

The defensive operation to protect the 1,400,000 civilian evacuees was part of the Leningrad counter-siege operations under the command of Andrei Zhdanov, Kliment Voroshilov, and Aleksei Kuznetsov. Additional military operations were carried out in coordination with Baltic Fleet naval forces under the general command of Admiral Vladimir Tributs. The Ladoga Flotilla under the command of V. Baranovsky, S.V. Zemlyanichenko, P.A. Traynin, and B.V. Khoroshikhin also played a major military role in helping with evacuation of the civilians.

Supplying the defenders[edit]

To sustain the defence of the city, it was vitally important for the Red Army to establish a route for bringing a constant flow of supplies into Leningrad. This route was effected over the southern part of Lake Ladoga and the corridor of land which remained unoccupied by Axis forces between Lake Ladoga and Leningrad. Transport across Lake Ladoga was achieved by means of watercraft during the warmer months and land vehicles driven over thick ice in winter (hence the route becoming known as "The Ice Road"). The security of the supply route was ensured by the Ladoga Flotilla, the Leningrad PVO Corps, and route security troops. Vital food supplies were thus transported to the village of Osinovets, from where they were transferred and transported over 45 km via a small suburban railway to Leningrad.[57] The route would also be used to evacuate civilians from the besieged city. This was because no evacuation plan had been made available in the chaos of the first winter of the war, and the city was completely isolated until 20 November 1941, when the ice road over Lake Ladoga became operational.

This road was named the Road of Life (Russian: Дорога жизни). As a road it was very dangerous. There was the risk of vehicles becoming stuck in the snow or sinking through broken ice caused by the constant German bombardment. Because of the high winter death toll the route also became known as the "Road of Death". However, the lifeline did bring military and food supplies in and took civilians and wounded soldiers out, allowing the city to continue resisting their enemy.

Effect on the city[edit]

Main article: Effect of the Siege of Leningrad on the city

The two-and-a-half year siege caused the greatest destruction and the largest loss of life ever known in a modern city.[21][58]On Hitler's express orders, most of the palaces of the Tsars, such as the Catherine Palace, Peterhof Palace, Ropsha,Strelna, Gatchina, and other historic landmarks located outside the city's defensive perimeter were looted and then destroyed, with many art collections transported to Nazi Germany.[59] A number of factories, schools, hospitals and other civil infrastructure were destroyed by air raids and long range artillery bombardment.

The 872 days of the siege caused extreme famine in the Leningrad region through disruption of utilities, water, energy and food supplies. This resulted in the deaths of up to 1,500,000[60] soldiers and civilians and the evacuation of 1,400,000 more, mainly women and children, many of whom died during evacuation due to starvation and bombardment.[1][2][4] Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery alone in Leningrad holds half a million civilian victims of the siege. Economic destruction and human losses in Leningrad on both sides exceeded those of the Battle of Stalingrad, theBattle of Moscow, or the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The siege of Leningrad is the most lethal siege in world history, and some historians speak of the siege operations in terms of genocide, as a "racially motivated starvation policy" that became an integral part of the unprecedented German war of extermination against populations of the Soviet Union generally.[61][62]

Civilians in the city suffered from extreme starvation, especially in the winter of 1941-42. From November 1941 to February 1942 the only food available to the citizen was 125 grams of bread per day, of which 50-60% consisted of sawdust and other inedible admixtures. For about two weeks at the beginning of January 1942, even this food was available only for workers and military personnel.[citation needed] In conditions of extreme temperatures, down to −30 °C (−22 °F), and city transport being out of service, even a distance of a few kilometers to a food distributing kiosk created an insurmountable obstacle for many citizens. Deaths peaked in January-February 1942 at 100,000 per month, mostly from starvation.[63] People often died on the streets, and citizens soon became accustomed to the sight of death.

Cannibalism[edit]

While reports of cannibalism appeared in the winter of 1941-42, NKVD records on the subject were not published until 2004. Most evidence for cannibalism that surfaced before this time was anecdotal. Anna Reid points out that "for most people at the time, cannibalism was a matter of second-hand horror stories rather than direct personal experience."[64] Indicative of Leningraders' fears at the time, police would often threaten uncooperative suspects with imprisonment in a cell with cannibals.[65] Dimitri Lazarev, a diarist during the worst moments in the Leningrad siege, recalls his daughter and niece reciting a terrifying nursery rhyme adapted from a pre-war song:

- A dystrophic walked along

With a dull look

In a basket he carried a corpse's arse.

I'm having human flesh for lunch,

This piece will do!

Ugh, hungry sorrow!

And for supper, clearly

I'll need a little baby.

I'll take the neighbours',

Steal him out of his cradle.[66] - NKVD files report the first use of human meat as food on 13 December 1941.[67] The report outlines thirteen cases which range from a mother smothering her eighteen-month-old to feed her three older children to a plumber killing his wife to feed his sons and nieces.[67]By December 1942, the NKVD arrested 2,105 cannibals dividing them into two legal categories: corpse-eating (trupoyedstvo) and person-eating (lyudoyedstvo). The latter were usually shot while the former were sent to prison. The Soviet Criminal Code had no provision for cannibalism so all convictions were carried out under Code Article 59--3, "special category banditry".[68]Instances of person-eating were significantly lower than that of corpse-eating; of the 300 people arrested in April 1942 for cannibalism, only 44 were murderers.[69] 64% of cannibals were female, 44% were unemployed, 90% were illiterate, 15% were rooted inhabitants, and only 2% had any criminal records. More cases occurred in the outlying districts than the city itself. Cannibals were often unsupported women with dependent children and no previous convictions, which allowed for a certain level of clemency in legal proceedings.[70]Given the scope of mass starvation, cannibalism was relatively rare.[71] Far more common was murder for ration cards. In the first six months of 1942, Leningrad witnessed 1,216 such murders. At the same time, Leningrad was experiencing its highest casualty rate, as high as 100,000 people per month. Lisa Kirschenbaum notes "that incidents of cannibalism provided an opportunity for emphasizing that the majority of Leningraders managed to maintain their cultural norms in the most unimaginable circumstances."[71]

Soviet relief of the siege[edit]

On 9 August 1942, the Symphony No. 7 "Leningrad" by Dmitri Shostakovich was performedby the Leningrad Radio Orchestra. The concert was broadcast on loudspeakers placed in all the city and also aimed towards the enemy lines. The same day had been previously designated by Hitler to celebrate the fall of the city with a lavish banquet at Leningrad'sAstoria Hotel,[72] and was a few days before the Sinyavino Offensive.Sinyavino Offensive[edit]

Main article: Sinyavino Offensive (1942)The Sinyavino Offensive was a Soviet attempt to break the blockade of the city in early autumn 1942. The 2nd Shock and the 8th armies were to link up with the forces of the Leningrad Front. At the same time the German side was preparing an offensive, OperationNordlicht (Northern Light), to capture the city, using the troops freed up after the capture ofSevastopol.[73] Neither side was aware of the other's intentions until the battle started.The offensive started on 27 August 1942, with some small-scale attacks by the Leningrad front on the 19th, pre-empting "Nordlicht" by a few weeks. The successful start of the operation forced the Germans to redirect troops from the planned "Nordlicht" to counterattack the Soviet armies. The counteroffensive saw the first deployment of the Tiger tank, though with limited success. After parts of the 2nd Shock Army were encircled and destroyed, the Soviet offensive was halted. However the German forces had to also abandon their offensive on Leningrad.Operation Iskra[edit]

Main article: Operation IskraThe encirclement was broken in the wake of Operation Iskra (Spark), a full-scale offensive conducted by the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts. This offensive started in the morning of 12 January 1943. After fierce battles the Red Army units overcame the powerful German fortifications to the south of Lake Ladoga, and on 18 January 1943 the Volkhov Front's 372nd Rifle Division met troops of the 123rd Rifle Brigade of the Leningrad Front, opening a 10–12 km (6.2–7.5 mi)[verification needed] wide land corridor, which could provide some relief to the besieged population of Leningrad.Lifting the siege[edit]

The siege continued until 27 January 1944, when the Soviet Leningrad-Novgorod Strategic Offensive expelled German forces from the southern outskirts of the city. This was a combined effort by the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts, along with the 1st and 2nd Baltic Fronts. The Baltic Fleet provided 30% of aviation power for the final strike against the Wehrmacht.[55] In the summer of 1944, the Finnish Defence Forces were pushed back to the other side of the Bay of Vyborg and the Vuoksi River.Bibliography[edit]

- Barber, John; Dzeniskevich, Andrei (2005), Life and Death in Besieged Leningrad, 1941–44, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, ISBN 1-4039-0142-2

- Baryshnikov, N. I. (2003), Блокада Ленинграда и Финляндия 1941–44 (Finland and the Siege of Leningrad), Институт Йохана Бекмана

- Glantz, David (2001), The Siege of Leningrad 1941–44: 900 Days of Terror, Zenith Press, Osceola, WI, ISBN 0-7603-0941-8

- Goure, Leon (1981), The Siege of Leningrad, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA, ISBN 0-8047-0115-6

- Granin, Daniil Alexandrovich (2007), Leningrad Under Siege, Pen and Sword Books Ltd, ISBN 978-1-84415-458-6

- Kirschenbaum, Lisa (2006), The Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 1941–1995: Myth, Memories, and Monuments, Cambridge University Press, New York, ISBN 0-521-86326-0

- Klaas, Eva (2010), Küüditatu kirjutas oma mälestused raamatuks (in Estonian: A Deportee Published His Memories in Book) (in Estonian), Virumaa Teataja

- Lubbeck, William; Hurt, David B. (2010), At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North, Casemate, ISBN 1-935149-37-7

- Platonov, S. P. (ed.) (1964), Bitva za Leningrad, Voenizdat Ministerstva oborony SSSR, Moscow

- Reid, Anna (2011), Leningrad: The Epic Siege of World War II, 1941-1944, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8027-7882-6

- Salisbury, Harrison Evans (1969), The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad, Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-81298-3

- Simmons, Cynthia; Perlina, Nina (2005), Writing the Siege of Leningrad. Women's diaries, Memories, and Documentary Prose, University of Pittsburgh Press, ISBN 978-0-8229-5869-7

- Willmott, H. P.; Cross, Robin; Messenger, Charles (2004), The Siege of Leningrad in World War II, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7566-2968-7

- Wykes, Alan (1972), The Siege of Leningrad, Ballantines Illustrated History of WWII

Further reading[edit]

- Backlund, L. S. (1983), Nazi Germany and Finland, University of Pennsylvania. University Microfilms International A. Bell & Howell Information Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Baryshnikov, N. I.; Baryshnikov, V. N. (1997), Terijoen hallitus, TPH

- Baryshnikov, N. I.; Baryshnikov, V. N.; Fedorov, V. G. (1989), Finlandia vo vtoroi mirivoi voine (Finland in the Second World War), Lenizdat, Leningrad

- Baryshnikov, N. I.; Manninen, Ohto (1997), Sodan aattona, TPH

- Baryshnikov, V. N. (1997), Neuvostoliiton Suomen suhteiden kehitys sotaa edeltaneella kaudella, TPH

- Bethel, Nicholas; Alexandria, Virginia (1981), Russia Besieged, Time-Life Books, 4th Printing, Revised

- Brinkley, Douglas; Haskey, Mickael E. (2004), The World War II. Desk Reference, Grand Central Press

- Carell, Paul (1963), Unternehmen Barbarossa — Der Marsch nach Russland

- Carell, Paul (1966), Verbrannte Erde: Schlacht zwischen Wolga und Weichsel (Scorched Earth: The Russian-German War 1943–1944), Verlag Ullstein GmbH, (Schiffer Publishing), ISBN 0-88740-598-3

- Cartier, Raymond (1977), Der Zweite Weltkrieg (The Second World War), R. Piper & CO. Verlag, München, Zürich

- Churchill, Winston S., Memoires of the Second World War. An abridgment of the six volumes of The Second World War, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, ISBN 0-395-59968-7

- Clark, Alan (1965), Barbarossa. The Russian-German Conflict 1941–1945, Perennial, ISBN 0-688-04268-6

- Fugate, Bryan I. (1984), Operation Barbarossa. Strategy and Tactics on the Eastern Front, 1941, Presidio Press, ISBN 978-0-89141-197-0

- Ganzenmüller, Jörg (2005), Das belagerte Leningrad 1941–1944, Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn, ISBN 3-506-72889-X

- Гречанюк, Н. М.; Дмитриев, В. И.; Корниенко, А. И. (1990), Дважды, Краснознаменный Балтийский Флот (Baltic Fleet), Воениздат

- Higgins, Trumbull (1966), Hitler and Russia, The Macmillan Company

- Jokipii, Mauno (1987), Jatkosodan synty (Birth of the Continuation War), ISBN 951-1-08799-1

- Juutilainen, Antti; Leskinen, Jari (2005), Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen, Helsinki

- Kay, Alex J. (2006), Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder. Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940 – 1941, Berghahn Books, New York, Oxford

- Miller, Donald L. (2006), The Story of World War II, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-7432-2718-2

- National Defence College (1994), Jatkosodan historia 1–6, Porvoo, ISBN 951-0-15332-X

- Seppinen, Ilkka (1983), Suomen ulkomaankaupan ehdot 1939–1940 (Conditions of Finnish foreign trade 1939–1940), ISBN 951-9254-48-X

- Симонов, Константин (1979), Записи бесед с Г. К. Жуковым 1965–1966, Hrono

- Suvorov, Victor (2005), I Take My Words Back, Poznań, ISBN 9666968746

- Vehviläinen, Olli; McAlister, Gerard (2002), Finland in the Second World War: Between Germany and Russia, Palgrave

Timeline[edit]

1941[edit]

- April: Hitler intends to occupy and then destroy Leningrad, according to planBarbarossa and Generalplan Ost[74]

- 22 June: The Axis powers' invasion of Soviet Union begins with Operation Barbarossa.

- 23 June: Leningrad commander M. Popov, sends his second in command to reconnoitre defensive positions south of Leningrad.[75]

- 29 June: Construction of the Luga defence fortifications (Russian: Лужский оборонительный рубеж) begins[76] together with evacuation of children and women.

- June–July: Over 300,000 civilian refugees from Pskov and Novgorod escaping from the advancing Germans come to Leningrad for shelter. The armies of the North-Western Front join the front lines at Leningrad. Total military strength with reserves and volunteers reaches 2 million men involved on all sides of the emerging battle.[citation needed]

- 19–23 July: First attack on Leningrad by Army Group North is stopped 100 km (62 mi) south of the city.[citation needed]

- 27 July: Hitler visits Army Group North, angry at the delay. He orders Field Marshal von Leeb to take Leningrad by December.[74]

- 31 July: Finns attack the Soviet 23rd Army at the Karelian Isthmus, eventually reaching northern pre-Winter War Finnish-Soviet border.

- 20 August – 8 September: Artillery bombardments of Leningrad hit industries, schools, hospitals and civilian houses.

- 21 August: Hitler's Directive No.34 orders "Encirclement of Leningrad in conjunction with the Finns."[77]

- 20–27 August: Evacuation of civilians is blocked by attacks on railways and other exits from Leningrad.[78]

- 31 August: Finnish forces go on the defensive and straighten their front line.[41] This involves crossing the 1939 pre-Winter War border and occupation of municipalities of Kirjasalo and Beloostrov.[41]

- 6 September: German High Command's Alfred Jodl fails to persuade Finns to continue offensive against Leningrad.[43]

- 2–9 September: Finns capture the Beloostrov and Kirjasalo salients and conduct defensive preparations.[50][79]

- 8 September: Land encirclement of Leningrad is completed when the German forces reach the shores of Lake Ladoga.[21][74]

- 10 September: Joseph Stalin appoints General Zhukov to replace Marshal Voroshilov as Leningrad Front and Baltic Fleet commander.[80][31]:400

- 12 September: The largest food depot in Leningrad, the Badajevski General Store, is destroyed by a German bomb.[81]

- 15 September: von Leeb has to remove the 4th Panzer Group from the front lines and transfer it to Army Group Centerfor the Moscow offensive.[82]

- 19 September: German troops are stopped 10 km (6.2 mi) from Leningrad. Citizens join the fighting at the defence lines.[citation needed]

- 22 September: Hitler directs that "Saint Petersburg must be erased from the face of the Earth".[83]

- 22 September: Hitler declares, "....we have no interest in saving lives of the civilian population."[83]

- 8 November: Hitler states in a speech at Munich: "Leningrad must die of starvation."[21]

- 10 November: Soviet counter-attack begins, forcing Germans to retreat from Tikhvin back to the Volkhov River by 30 December, preventing them from joining Finnish forces stationed at the Svir River east of Leningrad.[84]

- December: Winston Churchill wrote in his diary "Leningrad is encircled, but not taken."[85]

- 6 December: Great Britain declared war on Finland. This was followed by declaration of war from Canada, Australia, India and New Zealand.[86]

1942[edit]

- 7 January: Soviet Lyuban Offensive Operation is launched; it lasts 16 weeks and is unsuccessful, resulting in the loss of the 2nd Shock Army.

- January: Soviets launch battle for the Nevsky Pyatachok bridgehead in an attempt to break the siege. This battle lasts until May 1943, but is only partially successful. Very heavy casualties are experienced by both sides.

- 4–30 April: Luftwaffe operation Eis Stoß (ice impact) fails to sink Baltic Fleet ships iced in at Leningrad.[87]

- June–September: New German railway-mounted artillery bombards Leningrad with 800 kg (1,800 lb) shells.

- August: The Spanish Blue Division (División Azul) transferred to Leningrad.

- 9 August 1942: The Symphony No. 7 "Leningrad" by Dmitri Shostakovich was performed in the city.

- 14 August – 27 October: Naval Detachment K clashes with Leningrad supply route on Lake Ladoga.[21][33][52]

- 19 August: Soviets begin an eight-week-long Sinyavino Offensive, which fails to lift the siege, but thwarts German offensive plans (Nordlicht).[88]

1943[edit]

- January–December: Increased artillery bombardments of Leningrad.

- 12–30 January: Operation Iskra penetrates the siege by opening a land corridor along the coast of Lake Ladoga into the city. The blockade is broken.

- 10 February – 1 April: The unsuccessful Operation Polyarnaya Zvezda attempts to lift the siege.

1944[edit]

- 14 January – 1 March: Several Soviet offensive operations begin, aimed at ending the siege.

- 27 January: Siege of Leningrad ends. Germans forces pushed 60–100 km away from the city.

- January: Before retreating the German armies loot and destroy the historical Palaces of the Tsars, such as the Catherine Palace, Peterhof Palace, the Gatchina Palace and the StrelnaPalace. Many other historic landmarks and homes in the suburbs of St. Petersburg are looted and then destroyed, and a large number of valuable art collections are moved to Nazi Germany.

During the siege, 3,200 residential buildings, 9,000 wooden houses were burned, and 840 factories and plants were destroyed in Leningrad and suburbs.[89]

Defensive operations[edit]

The Leningrad Front (initially the Leningrad Military District) was commanded by MarshalKliment Voroshilov. It included the 23rd Army in the northern sector between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, and the 48th Army in the western sector between the Gulf of Finland and the Slutsk–Mga position. The Leningrad Fortified Region, the Leningrad garrison, the Baltic Fleet forces, and Koporye, Southern and Slutsk–Kolpino operational groups were also present.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Siege of Leningrad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

Leningraders on Nevsky Prospect during the siege, 1942 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 725,000 | 930,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

1942: 267,327 total casualties (KIA, WIA, MIA)[6] 1943: 205,937 total casualties (KIA, WIA, MIA)[7] 1944: 21,350 total casualties (KIA, WIA, MIA)[8] Total: 579,985 casualties | 1,017,881 killed, captured or missing[9] 2,418,185 wounded and sick[9] Total: 3,436,066 casualties Civilians:[9] 642,000 during the siege, 400,000 at evacuations | ||||||

| ||

| ||

Background[edit]

The capture of Leningrad was one of three strategic goals in the German Operation Barbarossa and the main target of Army Group North. The strategy was motivated by Leningrad's political status as the former capital of Russia and the symbolic capital of the Russian Revolution, its military importance as a main base of the Soviet Baltic Fleet and its industrial strength, housing numerous arms factories.[12] By 1939 the city was responsible for 11% of all Soviet industrial output.[13] It has been reported that Adolf Hitler was so confident of capturing Leningrad that he had the invitations to the victory celebrations to be held in the city's Hotel Astoria already printed.[14] Although various theories have been forwarded aboutNazi Germany's ultimate plans for Leningrad, including renaming the city Adolfsburg (as claimed by Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski)[15] and making it the capital of the new Ingermanland province of the Reich in Generalplan Ost, it is clear that Hitler's intention was to utterly destroy the city and its population. According to a directive sent to Army Group North on 29 September, "After the defeat of Soviet Russia there can be no interest in the continued existence of this large urban center. [...] Following the city's encirclement, requests for surrender negotiations shall be denied, since the problem of relocating and feeding the population cannot and should not be solved by us. In this war for our very existence, we can have no interest in maintaining even a part of this very large urban population."[16] Hitler's ultimate plan was to raze Leningrad to the ground and give areas north of the River Neva to the Finns.[17][18]

| ||

The Siege of Leningrad, also known as the Leningrad Blockade(Russian: блокада Ленинграда, transliteration: blokada Leningrada) was a prolonged military blockade undertaken mainly by the GermanArmy Group North against Leningrad, historically and currently known as Saint Petersburg, in the Eastern Front theatre of World War II. The siege started on 8 September 1941, when the last road to the city was severed. Although the Soviets managed to open a narrow land corridor to the city on 18 January 1943, the siege was only lifted on 27 January 1944, 872 days after it began. It was one of the longest and most destructive sieges in history and possibly the costliest in terms of casualties.[10][11]