Learning & Values » Jewish History » Chassidic Personalities » The Rebbe’s Prison Diary

Chapter VI: Prison Regulations

From the writings of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak of Lubavitch

http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/2986/jewish/Chapter-VI-Prison-Regulations.htm

The prison rules are:

1) The officials were prohibited from chatting with the prisoners; 2) All the cells were to be under double lock; 3) The prisoners were required to go to sleep and awaken at the scheduled time; 4) It was forbidden to sleep during the day; 5) It was prohibited to cover up the observation hole; 6) It was forbidden to look out of the cell window (though it was impossible to see anything anyway); 7) It was forbidden to throw anything through the window; 8) It was forbidden to smoke at night; 9) It was forbidden to light a candle in the room; 10) It was forbidden to converse at night; 11) From the hour of eleven at night until seven in the morning one could not request anything, this being the period between going to sleep and awakening; 12) It was forbidden to break the utensils in the cell(?); 13) Every prisoner was obligated to wash the floor of his cell; 14) Every prisoner had to submit himself to the authority of the prison guard; 15) If a prisoner defied the instructions of the guard or violated any of the above regulations, the guard was authorized to punish him according to his judgment by withholding food or hot water for a day or two. He could also refer this to the division head and recommend punitive punishment in a solitary confinement cell for a day or two, and in some instances, even for a week.

The daily schedule of the prison was as follows:

1) In the morning the prisoners were woken with the command: "Awake, awake, it is time to get up." Upon hearing these instructions all prisoners were obligated to get out of bed. The guard peered through the door opening, and woe to the prisoner whom the guard found reclining on his bed or stretched out on the floor after the morning call!

2) An announcement was heard, "Receive bread; prepare to receive bread." At that time someone opened the lock on the small window in the cell door, but there was yet another lock. The prisoners stood waiting for the second guard, who opened the second lock and who was in turn followed by the individual distributing the bread.

3) A kilo of black bread was distributed to each prisoner for the entire day, and usually each prisoner left over large chunks of it.

It was a source of joy for the prisoner, at the time of the door crevice opening, to see another human being, whoever he might be. Then the prisoner could also see the outer wall and enjoy inhaling the cold air from the balcony suddenly piercing through the gap. A moment after the bread distribution, the opening was closed with one lock.

4) A short while later, the announcement was heard, "Prepare to receive hot water." Each prisoner, upon entering his cell, received a wooden spoon, a bowl, and a large aluminum pitcher-like cup. Then the prisoners stood in readiness to receive this sweet gift-hot water.

5) An announcement was heard, "Prepare for lunch." Each prisoner cleaned his plate and spoon in anticipation of receiving his meal. There was lively speculation among the prisoners about what the fare would be that day.

6) Again the call was heard to prepare to receive porridge for the evening meal. Once again, there was animated movement within the room, one prisoner stating that he would take the food but not eat, another saying he would accept and eat, and the third asserting he would refuse the food. The gap in the door opened and the orderly filled the dishes with black porridge.

7) The call was heard, "Prepare to receive hot water." Twice during the day a pitcher of hot water was given to each prisoner, but no more than one pitcher. Usually the pitcher was received by its handle; however, sometimes the orderlies apportioning the water instructed the prisoner to grasp the pitcher itself, not by its handle, with the intention of making the prisoner hold the burning hot utensil. Also, each prisoner was obligated to receive his own ration.

When I declined to arise from my place to personally accept my portion of food and my cup of hot water (on Friday the seventeenth day of Sivan, because on Wednesday and Thursday, and until the second serving of hot water on Friday, I fasted), I remained without water. Only later was it brought especially for me.

8) A call went out: "Room Number such-and-such, prepare for your stroll."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This announcement was received gladly by the prisoners, who waited for it all day-a full twenty-four hours-for it is a legal requirement to provide fifteen minutes of walking daily for each prisoner-to walk outside under the surveillance of a special group of guards.

This walk enabled the prisoners to be briefly freed from the cell enclosure, to breathe fresh air and gaze upon the sky; to walk two hundred yards, and to descend the steel ladders. Moreover, it provided an even greater opportunity: to see people and perhaps, discern a familiar face. The prison held thousands of people from varying backgrounds, many of them eminent and distinguished: skilled doctors, engineers, lawyers, advocates, businessmen, clergymen, people of different faiths, the aged and the young, middle aged, people of different skills, and many, many more.

The prisoners gave much thought to this "outing." Firstly, they reflected on how to derive some personal advantage, in addition to breathing the fresh air. At times one could succeed in seeing a friend, and if opportunity smiled, communication could occur through a subtle gesture, despite the rigorous supervision.

The stroll gave the prisoner something to look back upon when he returned to the cell. Sometimes he would return more broken than he left for having seen certain people, and sometimes, it bolstered the spirit, but whatever its effect, it was of great significance to the prisoners.

There was no fixed time for this stroll, and it could occur at any time during the twelve hours from the time of awakening until seven o'clock in the evening. Upon hearing the number of their cells announced, the prisoners prepared for the anticipated pleasure. Each brief moment of waiting seemed like a long time.

There was a special regimen to this interlude. After the announcement to prepare for the walk, a special person came to peer through the door opening to see if the prisoners were ready. Shortly afterwards, the door opened and a special orderly appeared with a contingent of armed soldiers, who accompanied the prisoners.

The commander of these soldiers was as dark as coal in complexion, tall, a cedar tree with broad shoulders. He was stalwart in build and his uniform was red and black. He was heavily armed, and he resembled a destructive demon capable of consuming a hundred prisoners with one menacing stare. His voice was deep like a lions; he constantly gnashed his teeth. He yearned to torture and oppress these creatures: How gratified he would be if he could crush one of these gnats!

Standing at the open doorway, the commander surveyed the activity in the cell. He then called the prisoners to go to their walk. Like sheep, they filed out. The officer closed the door and lead the insects out to creep upon the ground. (This was the officers descriptive phrase as he led them forward.) In this way, they could refresh themselves from the "sweet pleasantness of the pure ai"r(?!) in the courtyard of the house of death-enclosed on all sides with the walls of the various structures of the Spalerno fortress.

(I had been informed of the following-I personally did not go to walk, even once.) The walking area was approximately eighty meters. In the center of the yard a wooden platform had been built taller than the height of a person. Upon it stood the supervising guard, and it was his responsibility to see that the prisoners observed all the positive and negative regulations of this stroll.

The positive rules for the walk were as follows:

A) To walk along the designated path, which circled the observation tower; B) The prisoners of each cell were to walk together; C) There had to be constant movement, it was forbidden to stand or sit.

The prohibitions for the walk were as follows:

A) It was forbidden to run; the prisoners had to walk slowly; B) The prisoners were not to speak aloud; they would only communicate secretly; C) The prisoners were not to walk with upright posture, thus preventing them from staring into the face of another prisoner; D) It was forbidden to direct one's gaze toward any window of the prison-fortress; E) It was forbidden to pick up any object from the ground; F) It was forbidden to throw anything; G) It was forbidden to wink with the eyes; H) It was forbidden to make any gesture with either one's hand or foot; I) It was forbidden to speak to any of the accompanying guards; J) It was forbidden to give or receive a cigarette.

Suddenly the command was sounded repeatedly: "The walk is over! Stand! Line up! Stand in order!"

At this point all the prisoners of one room were to stand together, leg-to-leg and shoulder-to-shoulder. A second command was given to march forward, and they advanced to the entrance way. Another command was given to form a line, one prisoner behind the other, and they began entering under the guard of soldiers. Each person proceeded to his cell. The cell doors were opened, and the imprisoned proceeded to their cages like submissive, bent-over goats.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

9) The announcement was made to lie down and sleep, which caused fear among the prisoners. For if the supervisor were to peer through the peephole and observe any delay, he was authorized to punish the inmates. The nighttime was more dangerous, for he had greater leeway to discipline prisoners. This low-ranking guard could mete out "light" punishment without asking the section head. A lenient punishment was to sleep the night in the dark, humid subterranean dungeon with rancid air amidst vermin and rats. This was considered a light punishment, a subtle hint to ensure conformity with prison discipline, like an admonishing adult waving his finger at the nose of a child.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Most interesting is the story innocently told by prisoner S. This man is unable to lie, completely unsophisticated and accustomed to relate what he knows without embellishment or exaggeration. S. is the speaker:

"It was the first day of my imprisonment and I was unaware of the prison regulations. I was the only person in this cell at that time, and when they ordered me to go to sleep, I was not really tired, so I sat and smoked a cigarette. The guard glanced through the cell window and angrily ordered me to lay upon my bed. I answered with an abusive word of refusal. I hadn't yet finished my cigarette, when the door opened abruptly and the guard commanded me to follow him. I did. We descended ladder after ladder until we were in the corridor of the basement of the building. The guard opened one of the doors and instructed me to enter. I went into the cell thinking that he would follow me, but in an instant I heard the shutting of the cell door.

"I took a step" -- S. relates -- "and found myself in oozing slime. The stench was suffocating. I lit a match. The size of the room was ten square feet. The walls were wet with moisture, and all kinds of creatures were crawling up and down the walls: white, black, long and large, and very frightful. The mud reached my ankles and I stood there all night. From time to time, I would have to push away the huge rodents that leaped at me with fearful, terrifying shrieks.

"It seemed to me that a day had already passed

[What about food? asked K.]

"There, a person has no desire to eat, nor even to smoke; you lose your desire for anything in that frightening cell. I heard the door being opened and I thought, 'Now they will take me to be shot.'

"I heard a whistle and the harsh command: 'Come here.'

"I replied: 'I can't see anything. Where should I go?'

"The official lit up the room and I saw a steel bed, just as here, but the sight was terrifying!

'Leave!' shouted the official, and immediately I left the room.

'Go up the stairs,' he commanded, and I thought to myself-Thank G-d, I will not die at the hand of the firing squad.

'Now,' said the officer, 'you will know how to address an official. It is forbidden to speak offensively to prison authorities. You are a prisoner and I am your officer. I am taking you to sleep-will you sleep?'

'Yes, your Excellency, I will sleep.'

"Instantly he hit me several times across my cheek. I was confused and unsure of the reason for his blows.

'What sort of "excellency" am I to you?' he raged. 'You vile being, slave of the White Russians, spy. I will confine you to the cellar for three days, not just for the three hours you were locked in!'

"I began to cry and plead, 'You are my father, my dearest, my lord and master; I will obey.'

"In quick succession he struck me three times. The blows were painful; my teeth shook and blood flowed from my nose. I maintained my self-control and tried to stand at respectful attention as appropriate before a person of rank. I still remembered the discipline of the army in the old days. I was a man! I served my Czar four years. I fought in the Russo-Japanese war. I have seen generals, and I know that order is order-discipline, not games. You remain a faithful soldier until your last breath, not like the youths now who sing prattle commands of 'Right' and 'Left,' and act like confused puppets.

'What sort of "master" am I to you?' said the officer. 'You must call me Tovarishtch -"Comrade." There are no longer any masters; now we are all comrades.'

'Very well, so be it, Comrade,' I answered, 'I will no longer address you in that way.'

"Again he struck me with his fist and said, 'What sort of "Comrade" am I to you? That is not the proper way to address an official. You must constantly remember that you are a prisoner and that I am your officer. You must say "Comrade Officer."'

"Weak and broken, I walked forward. I wanted to sleep, I wanted to smoke. My teeth hurt and I felt pain in my sides. As I walked, I kept repeating to myself, Comrade Officer. I must not forget it, I thought, woe to me if I forget! How pleasant it would be to sleep once again on the bed in my cell."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[The prison rules - continued]

10) Every day pencil and paper were provided for prisoners to write requests to any official: either the section head, the investigator, the defense attorney, or the prison doctor. The pencil was provided for an hour or two and had then to be returned, because writing was generally forbidden.

11) Once a week, on Wednesday, the prisoner could send home his underwear for laundering; he could also return empty food utensils received from home. These were to be accompanied by an itemized list of what he was forwarding; one word might be added about the state of his health, whether he was well or ill. On the other side of the paper he could request food or clothing.

12) Once a week, on Friday, food was brought for the prisoners to last for the week. There was a special procedure regarding the transfer of these objects until they arrived in the storage room of the head of each prisoner's section. Aside from the initial examination made when the objects were first brought to the administrative headquarters of Spalerno, there was a second check when they were given to the prisoners in the storage room of this section head.

Investigator's Name: Lulav . . .From when do you know the Rebbe Schneersohn? In summer of 1920 I saw him every day until he went to Moscow in September 1921. I know that in summer 1921 Rebbe Schneersohn was called to Cheka and they told him of plans to exile him to the north of Russia. Who turns to the Rebbe Schneersohn? Many Jews turn to him. They ask his advice. What type of Jews? Many of them are hiding from the G.P.U.. The Rebbe Schneersohn tells them to stay underground and not to go to the G.P.U. What were the circumstances? In the end of 1896 I was a member of the Bund, and afterwards I was the party representative of the "Jewish Socialist Workers Party" to the Sejm. In 1906 I was sent to Lubavitch. There I got to know the Rebbe Schneersohn – the father and the son. Why were you sent to Lubavitch? To solve a problem with a student of the Yeshivah who was a member of our party. What happened? In the Yeshivah they realized that he was a member of our party, and when he returned from a meeting they stopped him and placed him in a locked room. The party members took up arms and went to free the student. The Yeshivah students were there with sticks but we fired into the air and they ran away. Schneersohn, the son, passed the information on to the police and the police stopped the party members who went to save the student. How did you come into the picture? After this incident they sent me to Lubavitch to deal with Schneersohn, the son. I had three demands: 1) To free our party members. 2) To absolve the excommunication imposed on the student's family. 3) To give 5,000 rubles to the party. What was Schneersohn's response? He agreed to the first two conditions but not to the third one. What was your response? We began various types of threats to Schneersohn. We also threw stones through his windows.

Investigator's Name: Lulav . . .From when do you know the Rebbe Schneersohn? In summer of 1920 I saw him every day until he went to Moscow in September 1921. I know that in summer 1921 Rebbe Schneersohn was called to Cheka and they told him of plans to exile him to the north of Russia. Who turns to the Rebbe Schneersohn? Many Jews turn to him. They ask his advice. What type of Jews? Many of them are hiding from the G.P.U.. The Rebbe Schneersohn tells them to stay underground and not to go to the G.P.U. What were the circumstances? In the end of 1896 I was a member of the Bund, and afterwards I was the party representative of the "Jewish Socialist Workers Party" to the Sejm. In 1906 I was sent to Lubavitch. There I got to know the Rebbe Schneersohn – the father and the son. Why were you sent to Lubavitch? To solve a problem with a student of the Yeshivah who was a member of our party. What happened? In the Yeshivah they realized that he was a member of our party, and when he returned from a meeting they stopped him and placed him in a locked room. The party members took up arms and went to free the student. The Yeshivah students were there with sticks but we fired into the air and they ran away. Schneersohn, the son, passed the information on to the police and the police stopped the party members who went to save the student. How did you come into the picture? After this incident they sent me to Lubavitch to deal with Schneersohn, the son. I had three demands: 1) To free our party members. 2) To absolve the excommunication imposed on the student's family. 3) To give 5,000 rubles to the party. What was Schneersohn's response? He agreed to the first two conditions but not to the third one. What was your response? We began various types of threats to Schneersohn. We also threw stones through his windows.  The Chassidic Discourse "Baruch Hagomel" penned by the Rebbe on the day of his liberation.

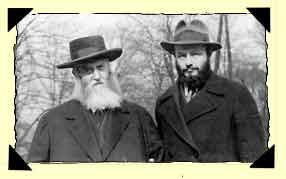

The Chassidic Discourse "Baruch Hagomel" penned by the Rebbe on the day of his liberation. The Rebbe with his son-in-law and successor,

The Rebbe with his son-in-law and successor,  A New Tork Times clipping about the Rebbe.

A New Tork Times clipping about the Rebbe.  A clipping fromthe Baltimore News concerning the Rebbe.

A clipping fromthe Baltimore News concerning the Rebbe.  The Rebbe in his stateroom aboard the S.S. Drottingholm upon his arrival in New York

The Rebbe in his stateroom aboard the S.S. Drottingholm upon his arrival in New York