http://ezinearticles.com/?Billy-Jack&id=5915606

EZINEARTICLES.COM

Plot[edit]

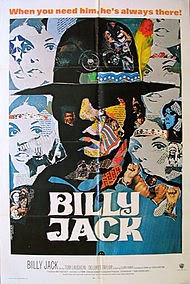

Billy Jack is a "half-breed" American Navajo Indian[citation needed], a Green Beret Vietnam War veteran, and a hapkido master. The character made his début in The Born Losers(1967), a "biker film" about a motorcycle gang terrorizing a California town. Billy Jack rises to the occasion to defeat the gang when defending a college student with evidence against them for gang rape.

In the second film, Billy Jack, the hero defends the hippie-themed Freedom School and students from townspeople who do not understand or like the counterculture students. The school is organized by Jean Roberts (Delores Taylor).

In one scene, a group of Indian children from the school go to town for ice cream and are refused service and then abused and humiliated by Bernard Posner and his gang. This prompts a violent outburst by Billy. Later, Billy's girlfriend Jean is raped and an Indian student is murdered by Bernard (David Roya), the son of the county's corrupt political boss (Bert Freed). Billy confronts Bernard and sustains a gunshot wound before killing him with a hand strike to the throat, after Bernard was having sex with a 13-year-old girl. After a climactic shootout with the police, and pleading from Jean, Billy Jack surrenders to the authorities and is arrested. As he is driven away, a large crowd of supporters raise their fists as a show of defiance and support. The plot continues in the sequel, The Trial of Billy Jack.

Influence[edit]

Marketed as an action film, the story focuses on the plight of Native Americans during the civil rights movement. It attained a cult following among younger audiences due to its youth-oriented, anti-authority message and the then-novel martial arts fight scenes which predate the Bruce Lee/kung fu movie trend that followed.[7] The centerpiece of the film features Billy Jack, enraged over the mistreatment of his Indian friends, fighting racist thugs using hapkido techniques.

Billy Jack's wardrobe (black T-shirt, blue denim jacket, blue jeans, and a black hat with a beadwork band) would become nearly as iconic as the character.

The second major movie to make use of the word "fuck" (MASH being the first). A black student says the words "fucked up" during the scene where the Freedom school students are talking about the "Second Coming".

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wovoka

Wovoka

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the Northern Paiute religious leader. For the Redbone song, see Wovoka (album).

| Wovoka | |

|---|---|

Wovoka – Paiute spiritual leader and creator of the Ghost Dance

| |

| Tribe | Northern Paiute |

| Born | c. 1856 Smith Valley, Nevada |

| Died | September 20, 1932 Yerington, Nevada |

| Nickname(s) | Jack Wilson |

| Known for | Spiritual leader and creator of the Ghost Dance |

| Resting place | Schurz, Nevada |

Wovoka (c. 1856 - September 20, 1932),[1] also known as Jack Wilson, was the Northern Paiute religious leader who founded the Ghost Dance movement. Wovoka means "cutter"[2]or "wood cutter" in the Northern Paiute language.

Further reading[edit]

- Michael Hittman, Wovoka and the Ghost Dance, Bison Books 1998, ISBN 0-8032-7308-8

- John Norman, Ghost Dance, Daw Books 1970, (a fictional account) ISBN 0-87997-501-6

Wovoka's Message:

The Promise of the Ghost Dancehttp://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/resources/archives/eight/gdmessg.htm[James Mooney, an ethnologist with the Bureau of American Ethnology, was sent to investigate the Ghost Dance movement in 1891. He obtained a copy of Wovoka's message from a Cheyenne named Black Short Nose, who had been part of a joint Cheyenne-Arapaho delegation that visited Wovoka in Nevada in August 1891. Wovoka (also known as Jack Wilson) delivered his message orally, and it was transcribed by a member of the group who had attended Carlisle Indian School. Mooney renders the "Carlisle English" of this transcription in a more grammatical form.]

- http://www.ghostdance.us/cgi-bin/email/contactus.cgi

- http://www.ghostdance.us/songs/songs-lyricsarapaho.html

- THE MESSIAH LETTERWhen you get home you must make a dance to continue five days. Dance four successive nights, and the last night keep us the dance until the morning of the fifth day, when all must bathe in the river and then disperse to their homes. You must all do in the same way.

I, Jack Wilson, love you all, and my heart is full of gladness for the gifts you have brought me. When you get home I shall give you a good cloud [rain?] which will make you feel good. I give you a good spirit and give you all good paint. I want you to come again in three months, some from each tribe there [the Indian Territory].

There will be a good deal of snow this year and some rain. In the fall there will be such a rain as I have never given you before.

Grandfather [a universal title of reverence among Indians and here meaning the messiah] says, when your friends die you must not cry. You must not hurt anybody or do harm to anyone. You must not fight. Do right always. It will give you satisfaction in life. This young man has a good father and mother. [Possibly this refers to Casper Edson, the young Arapaho who wrote down this message of Wovoka for the delegation].

Do not tell the white people about this. Jesus is now upon the earth. He appears like a cloud. The dead are still alive again. I do not know when they will be here; maybe this fall or in the spring. When the time comes there will be no more sickness and everyone will be young again.

Do not refuse to work for the whites and do not make any trouble with them until you leave them. When the earth shakes [at the coming of the new world] do not be afraid. It will not hurt you.

I want you to dance every six weeks. Make a feast at the dance and have food that everybody may eat. Then bathe in the water. That is all. You will receive good words again from me some time. Do not tell lies.

Biography[edit]

Wovoka was born in Smith Valley area southeast of Carson City, Nevada, around the year 1856. Wovoka's father may have been the religious leader variously known as "Tavibo" or "Numu-Taibo" whose teachings were similar to those of Wovoka. Regardless, Wovoka clearly had some training as a medicine man. Wovoka’s father died around the year 1870, and he was taken in by David Wilson, a rancher in the Yerington, Nevada area, and his wife Abigail. Wovoka worked on Wilson’s ranch and used the name Jack Wilson when dealing with European Americans. David Wilson was a devout Christian, and Wovoka learnedChristian theology and Bible stories while living with him.

Wovoka gained a reputation as a powerful medicine man early in adulthood and is now perceived to have been adept at magic tricks. One feat he often performed was being shot with a shotgun, which may have been similar to the bullet catch trick.[3] Reports of this feat potentially convinced the Lakota that their "ghost shirts" could stop bullets. Wovoka also performed a feat of levitation. One of his chief sources of authority among Paiutes was his alleged ability to control the weather. He was said to have caused a block of ice to fall out of the sky on a summer day, to be able to end drought with rain or snow, to light his pipe with the sun, and to form icicles in his hands.[4]

Wovoka claimed to have had a prophetic vision during the solar eclipse on January 1, 1889. Wovoka's vision entailed the resurrection of the Paiute dead and the removal of whites and their works from North America. Wovoka taught that in order to bring this vision to pass the Native Americans must live righteously and perform a traditional round dance, known as the Ghost dance, in a series of five-day gatherings. Wovoka's teachings spread quickly among many Native American peoples, notably the Lakota. Wovoka's vision brought about the question of his sanity[citation needed].

The Ghost Dance movement is known for being practiced by the victims of the Wounded Knee Massacre; Indian Agents, soldiers, and other federal officials were predisposed towards a cautious, wary, and defensive posture when dealing with a movement that was so mysterious to them. Important to note is that Wovoka’s preachings included messages of non-violence, but that two Miniconjou, Short Bull and Kicking Bear, instead emphasized the possible elimination of whites which contributed to the existing defensive attitude of the federal officials who were already fearful due to the unfamiliar Ghost Dance movement.

Wovoka died in Yerington on September 20, 1932 and is interred in the Paiute Cemetery in the town of Schurz, Nevada.[5]

Song of Wovoka,

Wovoka Biography

by Encyclopedia of World Biography

In response to a vision, Wovoka (1856-1932) founded the Ghost Dance religion. A complex figure, he was revered by Indians while being denounced as an impostor and a lunatic by the local settlers throughout his entire life.

In response to a vision, Wovoka (1856-1932) founded the Ghost Dance religion. A complex figure, he was revered by Indians while being denounced as an impostor and a lunatic by the local settlers throughout his entire life.

Based on a personal vision, Wovoka created the Ghost Dance religion of the late 1880's. A distorted interpretation of his beliefs and teachings was a contributing factor in the events leading to the Wounded Knee Massacre in late December of 1890. Wovoka's impact on the local Paiute people, and Native Americans throughout the West, continued beyond his death in 1932.

Until 1990 the documentation about Wovoka's life was scattered, and he was the subject of both speculation and misrepresentation. He was considered to have little importance after 1890. The only general account of his life was Paul Bailey's 1957 biography, which leaves the reader with the impression that Wovoka was a benign huckster. However, the meaning and effects of his life are much more complex. Key primary sources and a biographical summary are provided in Wovoka and the Ghost Dance by Michael Hittman, a Long Island University anthropologist. Hittman began studying the Yerington Paiute Tribe of Nevada in 1965, and the source book, completed twenty-five years later, is an extraordinary compilation (over 300 pages) of commentary and sources, including original manuscripts by personal acquaintances of Wovoka, photographs, newspaper accounts, government letters and reports, ghost dance songs, the views of other anthropologists, comments of surviving tribal members, and an extensive bibliography. Any serious study of the life of this famous prophet should start with this publication. According to Hittman, Wovoka was "a great man and a fake."

Wovoka was born about 1856 in Smith Valley or Mason Valley, Nevada, as one of four sons of Tavid, also known as Numo-tibo's, a well-known medicine man. (A link of Wovoka's father to an earlier Ghost Dance of 1870 in the region is unclear.) Both of Wovoka's parents survived into the twentieth Century. At about the age of fourteen Wovoka was sent to live with and work for the Scotch-English family of David Wilson. During this period he acquired the names Jack Wilson and Wovoka, meaning "Wood Cutter."

The religious influences upon Wovoka were diverse. Wovoka was clearly affected by the religious values of the pious United Presbyterian family; Mr. Wilson read the Bible each day before work. He lived in a region where traveling preachers were common and Mormonism prevalent. There is a possibility that Wovoka traveled to California and the Pacific Northwest, where he may have had contact with reservation prophets Smohalla and John Slocum.

At about the age of twenty he married Tumm, also known as Mary Wilson. They raised three daughters. At least two other children died.

he Ghost Dance Religion

Wovoka had promoted the Round Dance of the Numu people and was recognized as having some of his father's qualities as a mystic. A long-time acquaintance described the young Wovoka as "a tall, well proportioned man with piercing eyes, regular features, a deep voice and a calm and dignified mien." A local census agent referred to him as "intelligent," and a county newspaper added that he resembled "the late Henry Ward Beecher." Wovoka was known to be a temperate man during his entire life.

The turning point in Wovoka's life came in the late 1880's. In December of 1888 Wovoka may have been suffering from scarlet fever. He went into a coma for a period of two days. Observer Ed Dyer said, "His body was as stiff as a board." Because Wovoka's recovery had corresponded with the total eclipse of the sun on January 1, 1889, he was credited by the Numus for bringing back the sun, and thereby saving the universe.

After this apparent near death experience, Wovoka proclaimed that he had a spiritual vision with personal contact with God who gave him specific instructions to those still on earth. According to Wovoka, God told him of a transformation by the spring of 1891 when the deceased would again be alive, the game would again flourish, and the whites would vanish from the earth. He had also been instructed to share power with the President of the East, Benjamin Harrison. Until the time of the apocalypse, Wovoka counselled the living to work for the dominant population and attempt to live a morally pure life. The plan for the future could only be assured if believers followed the special patterns and messages of the Ghost Dance, which Wovoka taught his followers.

Local believers had already adopted a dependence on him to bring much needed rain. The national setting for Native Americans was such that the message of Wovoka would soon spread throughout the western territory of North America. Scott Peterson, author of Native American Prophesies, explains, "Wovoka's message of hope spread like wildfire among the demoralized tribes." Before long, representatives of over thirty tribes made a pilgrimage to visit Wovoka and learn the secrets of the Ghost Dance.

A Pyramid Lake agent dismissed Wovoka in November of 1890 as "a peaceable, industrious, but lunatic Pah-Ute," who "proclaimed himself an aboriginal Jesus who was to redeem the Red Man." Two weeks later, a writer for the Walker Lake Bulletin expressed concern about the 800 "sulky and impudent" male Indians who were participating in a dance at the Walker Lake Reservation. A day later the first known formal interview with Wovoka was conducted by United States Army Indian Scout Arthur I. Chapman. He had been sent to find the "Indian who impersonated Christ!" Chapman was not disturbed by what he found.

The most dynamic evidence of Wovoka's impact took place near the Badlands of South Dakota. Regional Sioux delegates, including Short Bull and Kicking Bear, returned with the message that wearing a Ghost Dance shirt would make warriors invulnerable to injury. Among those who accepted the assurance was the famous chief, Sitting Bull. The conditions were ideal for a message of deliverance in the Badlands: the buffalo were vanishing; the native residents were being pushed onto diminishing reservation lands as the designated area was opened to white settlement in 1989. The atmosphere is skillfully presented in a 1992 novel about the Lakota people, Song of Wovoka, which describes, "The end of their [Lakota] way of life seemed trivial compared to the very real possibility of extermination." The Lakota misinterpreted the teachings of Wovoka, namely of passivity and patience to wait for divine intervention, as a call to proactively rid the land of white settlers.

There emerged fear among white settlers and the military in the region. The uncertain future of the newly established states of North and South Dakota was being threatened by "the Ghost Dance craze." Memories of both the 1862 uprising in Minnesota and the debacle at Little Big Horn were still strong. Unable to enforce the ban of the Ghost Dance among the Lakota, Agent James McLaughlin of the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull, a respected Lakota leader, intentionally disrupting a plan for Sitting Bull's arrest by old colleague Buffalo Bill Cody, who would have secured the arrest without harming Sitting Bull. As reported by Indian scout Charles A. Eastman, on December 15, 1890, a protest broke out as soldiers seized Sitting Bull, which resulted in gunfire killing Sitting Bull, six Indian defenders, and six Indian police.

A few days later a seriously ill Big Foot and his band were marching to a place of surrender on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. An overwhelming force of 470 soldiers confronted them at Wounded Knee. In the process of a final disarmament, gunfire broke out. Over 200 Native Americans, many of them women and children, were killed. The next day, without ceremony, frozen bodies stripped of their Ghost Dance garments were tossed into a mass grave. For many this symbolized the end of resistance.

There is certainly no evidence that Wovoka intentionally promoted the type of confrontation that occurred at Wounded Knee. He later referred to his idea of an impenetrable shirt as a "joke." His associate Ed Dyer evaluated the situation: "I was thoroughly convinced that Jack Wilson had at no time attempted deliberately to stir up trouble. He never advocated violence. Violence was contrary to his very nature. Others seized upon his prophecies and stunts, and made more of them than he intended … in a way, once started, he was riding a tiger. It was difficult to dismount."

Within a few days of the atrocities at Wounded Knee, the local newspapers in Wovoka's region expressed concern about the fact that there were "within the radius of 40 miles … 1,000 able-bodied bucks, well armed." The Paiutes were getting "very saucy," claiming that "pretty soon they will own stores and ranches and houses … that county all belonged to them once, and that pretty soon they will take the farms and horses away from the white man." Government sources also expressed concern. Acknowledging that "the Messiah Craze" was "headquartered" in Nevada, Frank Campbell wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs on September 5, 1891: "The cause of its spreading so generally among Indians is the hope that these people have that some power greater than themselves may arrest and crush the oncoming flood of civilization that is destined soon to overwhelm them."

A month later, C. C. Warner, the openly antagonistic United States Indian Agent at Pyramid Lake, said he would not give Wovoka added "notoriety" by having him arrested. "I am pursuing the course with him of nonattention or silent ignoring." In December of 1892 he reported that although he found no local agitation, he "became suspicious that the 'Messiah' Jack Wilson was using an evil influence among foreign Indians which might result in a spring uprising among the Indians." His Farmer-In-Charge of the Walker River Reservation did a personal investigation. The following August, Warner announced that the Ghost Dance "fanaticism" was "a thing of the past" and that "the strongest weapon to be used against the movement is ridicule."

The Middle Years, 1890-1920

The role of Wovoka in the years after Wounded Knee has been generally overlooked. But it is clear that he did not fade into oblivion or hesitate to use his unusual fame and powers. An Indian Agent reported in June 1912 "that Jack Wilson is still held in reverence by Indians in various parts of the country, and he is still regarded by them as a great medicine man." Two years later he reinforced that statement, adding, "the influence of Jack Wilson the 'Messiah' of twenty five years ago is not dead." Indian Agent S. W. Pugh took a position quite different than that of C. C. Warner. When Jack Wilson sought an allotment on the reservation, he encouraged the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to help make it possible. "I would like to have him as he is still a power among his people and could be used to excellent advantage if here. He is a very intelligent Indian, and peaceably inclined apparently… . These people will follow him anywhere, and he has advanced ideas.

Although Wovoka had established a reputation as a strong, reliable worker as a young man, the reknown of the Ghost Dance phenomenon resulted in other uses of his time during the balance of his life. Attempts to bring him to both the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and the Midwinter Fair in San Francisco in 1904 apparently failed, but he made trips to reservations in Wyoming, Montana, and Kansas, as well as the former Indian territory of Oklahoma. Some trips lasted as long as six months. He was showered with gifts and as much as $1,200 in cash on a single trip. In 1924, historian-actor Tim McCoy delivered Wovoka by limousine to the set of a movie he was making In northern California. There he was treated with absolute reverence by Arapahos who had been hired for the film.

While at home Wovoka practiced another brisk form of enterprise. With the aid of his friend Ed Dyer and others he replied to numerous letters and requests for particular items, including thaumaturges and articles of clothing that he had worn. He had a fee for red paint, magpie feathers, etc. Conveniently, Dyer, his frequent secretary, was also a supplier. One of the most popular items was a hat that had been worn by "the Prophet." The usual price to a correspondent was $20. Dyer noted, "Naturally he was under the necessity of purchasing another from me at a considerable reduced figure. Although I did a steady and somewhat profitable business on hats, I envied him his mark-up which exceeded mine to a larcenous degree." Surprisingly, none of the response letters that Wovoka dictated have been found.

Despite his relative notoriety and financial security, Wovoka continued to live a simple life. As late as 1917, he was living in a two-room house built of rough boards. A visitor reported, "He lives purely Indian customs with very little household effects. They sleep on the floor and from all appearances also use the floor as their table for eating."'

Wovoka also had an interesting peripheral role in the "political" world. As early as November 1890 an ex-Bureau of Indian Affairs employee suggested that an official invitation to Washington, D.C., for Wovoka and some of his followers "might have a tendency to quiet this craze." His early vision of course included the view that he would share national leadership with then President Benjamin Harrison. In 1916, the Mason Valley News reported that Wovoka was considering a visit to President Woodrow Wilson to help "terminate the murderous war in Europe" (Wovoka's grandson, following the prediction of his grandfather, became a pilot and died a hero in World War II. ) In the 1920s, Wovoka was photographed at a Warren G. Harding rally. Perhaps the selection of Charles Curtis, a Sac-Fox from Kansas, as Vice President of the United States was a sign of the predicted millennium. Wovoka sent him a radiogram on March 3, 1929 stating, "We are glad that you are Vice President and we hope some day you will be President."

It is not possible to make an absolute judgement about the real talents of this Nevada mystic to determine which of his activities were the product of true inspiration and which merely legerdemain. There are many accounts of his accomplishments varying from making prophesies that came true and returning people from the dead to predicting weather, making rain, surviving shots from guns, and producing ice in the middle of summer. His associate Ed Dyer reflected, it is "very human to believe what we want to believe."

Final Years

Anthropologist Michael Hittman explains most of Wovoka's shamatic practice and beliefs in the context of his native culture and concludes, "Wovoka appears to have maintained faith in his original revelation and supernatural powers to the very end." Ed Dyer commented later, "His prestige lasted to the end." His services as a medicine man were in demand until shortly before his own death on September 29, 1932, from enlarged prostate cystitis. His wife of over fifty years had died just one month before. Yerington Paiute tribal member Irene Thompson expressed a local Numu reaction, "When he died, many people thought Wovoka will come back again."

A Reno newspaper, although giving a lengthy account of his life, basically dismissed him as a fraud: "'Magic' worked with the aid of a bullet-proof vest; white men's pills and some good 'breaks' in the weather made him the most influential figure of his time among the Indians." Scott Peterson, in his 1990 study of Native American prophets, argues that if Wovoka had not "set a date for the apocalypse … the Ghost Dance, with its vision of a brighter tomorrow, might still very well be a vital force in the world today."

In fact, elements of the Ghost Dance religion pervaded the practices of many tribes even after the tragedy of Wounded Knee. A form of the original dance is still performed by some Lakota today. Historian L. G. Moses describes Wovoka as "one of the most significant holy men ever to emerge among the Indians of North America." John Grim, in The Encyclopedia of Religion, gives the mystic credit for promoting "a pan-Indian identity." Hittman asserts that the key elements of "the Great Revelation" remain "honesty, the importance of hard work, the necessity of nonviolence, and the imperative of inter-racial harmony."

Final Years

Anthropologist Michael Hittman explains most of Wovoka's shamatic practice and beliefs in the context of his native culture and concludes, "Wovoka appears to have maintained faith in his original revelation and supernatural powers to the very end." Ed Dyer commented later, "His prestige lasted to the end." His services as a medicine man were in demand until shortly before his own death on September 29, 1932, from enlarged prostate cystitis. His wife of over fifty years had died just one month before. Yerington Paiute tribal member Irene Thompson expressed a local Numu reaction, "When he died, many people thought Wovoka will come back again."

A Reno newspaper, although giving a lengthy account of his life, basically dismissed him as a fraud: "'Magic' worked with the aid of a bullet-proof vest; white men's pills and some good 'breaks' in the weather made him the most influential figure of his time among the Indians." Scott Peterson, in his 1990 study of Native American prophets, argues that if Wovoka had not "set a date for the apocalypse … the Ghost Dance, with its vision of a brighter tomorrow, might still very well be a vital force in the world today."

In fact, elements of the Ghost Dance religion pervaded the practices of many tribes even after the tragedy of Wounded Knee. A form of the original dance is still performed by some Lakota today. Historian L. G. Moses describes Wovoka as "one of the most significant holy men ever to emerge among the Indians of North America." John Grim, in The Encyclopedia of Religion, gives the mystic credit for promoting "a pan-Indian identity." Hittman asserts that the key elements of "the Great Revelation" remain "honesty, the importance of hard work, the necessity of nonviolence, and the imperative of inter-racial harmony."

Wovoka's role as an "agitator" also remains significantly symbolic. In 1968, a former publisher of the Mason Valley News (which ignored the death of the famous resident in 1932) recalled Wovoka's stoical appearance in his elegant apparel on the streets of the small town: "Best human impression of a wooden Indian I ever seen. Oh, he was the only kind of individual that shook up the Army and Washington, D.C. Somebody today should." Five years later, after Dee Brown reminded Americans of the forgotten atrocity of American frontier history, members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) occupied the original site of Wounded Knee and engaged U.S. forces in battle.