- During the closing days of WWII, a National Guard Infantry Company is assigned the task of setting up artillery observation posts in a strategic area. Lieutenant Costa knows that Cooney is in command only because of 'connections' he had made state-side. Costa has serious doubts concerning Cooneys' ability to lead the group. When Cooney sends Costa and his men out, and refuses to re-enforce them, Costa swears revenge.

Attack!

Release Date: January 1st, 1956

Not Yet Rated1 hr. 47 min.

Plot Summary

Lt. Joe Costa (Jack Palance) is a part of Fragile Fox Company, a National Guard unit sent to a Belgian town in the final stages of World War II. Costa harbors some serious doubts about the leadership abilities of Captain Cooney (Eddie Albert), a coward who only secured his position because of his ties to Lt. Col. Bartlett (Lee Marvin). Cooney's inexperience and his open contempt for Costa threaten the lives of his men as they draw closer to Battle of the Bulge.

Lt. Joe Costa (Jack Palance) is a part of Fragile Fox Company, a National Guard unit sent to a Belgian town in the final stages of World War II. Costa harbors some serious doubts about the leadership abilities of Captain Cooney (Eddie Albert), a coward who only secured his position because of his ties to Lt. Col. Bartlett (Lee Marvin). Cooney's inexperience and his open contempt for Costa threaten the lives of his men as they draw closer to Battle of the Bulge.

Cast: Jack Palance, Eddie Albert, Lee Marvin, Robert Strauss, Richard Jaeckel, Buddy Ebsen, Jon Shepodd,Peter Van Eyck

Director: Robert Aldrich

Genres: War

Attack (1956 film)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Attack! | |

|---|---|

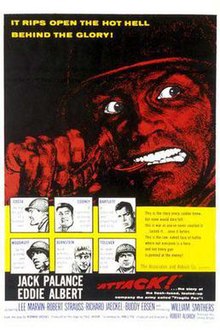

Attack theatrical poster

| |

| Directed by | Robert Aldrich |

| Produced by | Robert Aldrich |

| Screenplay by | James Poe |

| Based on | Fragile Fox by Norman Brooks |

| Starring | Jack Palance Eddie Albert Lee Marvin William Smithers Robert Strauss Buddy Ebsen |

| Music by | Frank De Vol |

| Cinematography | Joseph F. Biroc |

| Edited by | Michael Luciano |

Production

company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists (1955, original) MGM (2003, DVD) Filmedia (under license from MGM) (2013, Blu-Ray DVD) |

Release dates

|

|

Running time

| 107 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $810,000[1] |

| Box office | $2 million (US)[2] 1,493,421 admissions (France)[3] |

Attack, also known as Attack!, is a 1956 American anti-war drama film. It was directed by Robert Aldrich and starred Jack Palance, Eddie Albert, Lee Marvin, William Smithers, Robert Strauss, Richard Jaeckel, Buddy Ebsen andPeter van Eyck. The cinematographer was Joseph Biroc.

"A cynical and grim account of war",[4] the film is set in the latter stages ofWorld War II and tells the story of a front line combat unit led by a cowardly captain clearly out of his depth as well as a tougher subordinate and an executive officer who both threaten to do away with him. As the official trailer put it: "Not every gun is pointed at the enemy!"

The film won the 1956 Italian Film Critics Award.

Europe 1944: Fragile Fox is a company of American G.I.s from the National Guard of the United States based in a Belgian town near the front line. They are led by Captain Erskine Cooney (Eddie Albert), a man from a southwestern town called Riverview, Kentucky who appears to be better at handling red tape than military strategy. On the other hand, Cooney is a natural coward out of depth who freezes under fire and cannot bring himself to send more men into battle to reinforce those already under attack. The increasing and unnecessary loss of life is causing morale problems among the troops and trying the patience of Platoon Leader Lt. Joe Costa (Jack Palance), a bold and brave fighter and a natural leader of men, The Executive Officer, Lt. Harold Woodruff (William Smithers, in his first credited screen role) is the "voice of reason" who tries to keep the peace between Cooney and Costa. Both he and Costa are respected by the enlisted troops. While Woodruff tries to get Cooney reassigned to a desk job behind the lines, Costa hints at a more direct solution to the problem. It's a well-known fact that Cooney owes his position to battalion commander Lt. Col. Clyde Bartlett (Lee Marvin), a man who has known the Cooney family since he was a 14-year-old clerk in the office of Cooney's father, a top judge. The judge and his influence could be very useful to Bartlett's post-war political ambitions and it all depends on his and Cooney's war records. Neither Captain Cooney nor Bartlett are liked by the company: as PFC. Bernstein (Robert Strauss) puts it: "When you salute them two, you have to apologize to your arm."

When the Germans start the counter-attack known as the Battle of the Bulge, Bartlett orders Cooney to seize the town of La Nelle. Since there is no way of knowing if the Germans are there or not, Cooney overrules an all-out attack and decides that Costa should lead a reconnaissance mission. Costa agrees provided that both Cooney and Woodruff promise him to send in reinforcements if necessary. As he is about to leave, Costa warns Cooney of the consequences if he ever plays the "gutless wonder" again: "I'll shove this grenade down your throat and pull the pin!" As they approach La Nelle, the platoon comes under fire by German SS. Most of them are killed or injured. Costa and four of his men (Sergeant Tolliver, Bernstein, PFC. Ricks and Pvt. Snowden) take refuge in a farmhouse but find themselves under siege. When Costa calls for reinforcements, Cooney snaps, ignores the pressure from Woodruff to go in and turns to drink. A little strategy and deception enables Costa and his men to hold up and capture a German SS officer and a soldier, but when Panzers appear he has no choice but to call a retreat. He furiously tells Woodruff over the radio to warn Cooney that he's "coming back!"In the confusion that follows the retreat, Costa becomes MIA. The rest of the men manage to get back to the main town, though Ricks (James Goodwin) is killed in the escape, in addition to the many casualties during the initial move on La Nelle. The men show their contempt for Cooney: Bernstein spits at his feet and Tolliver rejects his offer of a drink, telling him that where he comes from "We don't drink with another man unless we respect him." Bartlett, who has just arrived, reprimands him for failing to send in his entire company to take La Nelle. As a result, the German Army is now approaching their position and he tells Woodruff and Cooney that they must hold their present position in spite of the German advance. Bartlett threatens to arrest Cooney if he falls back, as it would leave another company unprotected, and strikes Cooney after the coward begs to be reassigned. Woodruff warns Bartlett that he is going to lodge a complaint with General Parsons, the Colonel's superior, over the handling of the company. With the pressure building up, Cooney turns to drinking again, but Woodruff smashes the bottle, accuses him of "Got every man in this outfit thinking that the U.S. army is a mockery!". After that Cooney then breaks down, whimpering that he will never measure up to his father and telling Woodruff about having been beaten by his drunken father in order to "make a man" out of him, revealing that he's been a victim of child abuse in attempt to become a man. Bartlett has told him that he is in command "as a favor to the judge. He's always wanted a son, now I'm trying to give him one." Feeling sorry for Cooney, Woodruff tells him to sleep it off and is about to assume command when Costa suddenly reappears, determined to kill Cooney. As they argue, they are told by Cpl. Jackson (Jon Shepodd) that the town is being overrun by Germans. Costa grabs a Bazooka and bravely disables an enemy tank, but is gravely wounded when another tank drives over his arm.

Woodruff, Tolliver, Bernstein, Jackson and Snowden (Richard Jaeckel) take refuge in a basement but Bernstein is injured in the leg and, being a Jew, is unlikely to have his POW rights respected by the attacking SS. They try to get out but their way is blocked, and a drunken and erratic Cooney insists they are "holding for Clyde [Bartlett]". As they argue, Costa suddenly appears. Seriously injured in the arm and with only minutes of life left, he appeals to God to give him enough strength to kill Cooney, but he collapses and dies. Cooney mockingly kicks the gun away from him. With Costa dead, Cooney suggests that the rest of them surrender even though they have not been discovered. At that moment Woodruff warns him that he will shoot him if he does. When Cooney does make a move, Woodruff kills him.

Woodruff insists that Tolliver place him under arrest, but he and the other GIs reject this, claiming that "shooting him was just about the most just thing I ever seen." They then take turns shooting the dead Cooney themselves except Snowden who has left to see if the Germans heard the shots. Allied reinforcements arrive and the Germans retreat. Told by the men that Cooney was killed by the Germans, Bartlett appears to accept this and puts Woodruff in command. When the men ask Woodruff to confirm that he is now the C.O., there is some anxiety and hesitation in the room. Bartlett, an expert pokerplayer who knows all about bluffing, is momentarily suspicious.

Bartlett, who has always hated Cooney, contemptuously kicks him over, remarking "So the old judge wanted a son, huh? Looks like he had to lose one to get one." He gives Woodruff a field promotion to captain and tells him to forget about the threatened complaint to General Parsons; but he then announces that he is going to nominate Cooney for the Distinguished Service Cross. Outraged that a coward should be honoured in this way, Woodruff openly accuses Bartlett of manipulating the whole thing in order to get rid of Cooney, who was a liability, and get favors with his powerful father: "I may have pulled that trigger but you aimed the gun. You set this whole thing up so it would happen!" Bartlett is unconcerned, remarking that Woodruff has too much to lose if he makes the whole affair public. But Woodruff calls his bluff, goes to the radio and calls for General Parsons to complain about the company and to file a full report.

Cast[edit]

- Jack Palance as Lt. Joe Costa

- Eddie Albert as Capt. Erskine Cooney

- Lee Marvin as Lt. Col. Clyde Bartlett

- William Smithers as Lt. Harold "Harry" Woodruff

- Robert Strauss as Pfc. Bernstein

- Richard Jaeckel as Pvt. Snowden

- Buddy Ebsen as T/Sgt. Tolliver

- Jon Shepodd as Cpl. John Jackson

- Peter van Eyck as SS Captain

- James Goodwin as Pfc. Ricks

- Steven Geray as Otto, German NCO

- Jud Taylor as Pvt. Jacob R. Abramowitz (credited as Judson Taylor)

Production[edit]

The film was based on Norman Brooks's stage play, Fragile Fox. Director Aldrich bought the rights when he failed to obtain those for Irwin Shaw's The Young Lions and Norman Mailer's The Naked and the Dead.[5]

Due to the nature of the film, which cast officers as either cowards or Machiavellian manipulators, the US Defense Department refused to grant production assistance. Critics attacked this attitude, pointing out the heroic and noble behavior of other officers like Costa and Woodruff who were "more representative of the Army than the cowardly captain, who is clearly an exception."[5]

Aldrich is quoted, "The Army saw the script and promptly laid down a policy of no co-operation, which not only meant that I couldn't borrow troops and tanks for my picture — I couldn't even get a look at Signal Corps combat footage. I finally had to buy a tank for $1,000 and rent another from 20th Century-Fox."[6]

Aldrich directed Attack! without the big budget that other war productions were getting at the time. It was shot in thirty-two days on the back lot of RKO Studios with a small cast and budget and a few pieces of military equipment, including the two tanks.[5]

The opening title sequence depicting off-duty soldiers was created by Saul Bass.

Eddie Albert, who played the cowardly Cooney, was in reality a decorated hero in the WWII Pacific Theater. Before World War II commenced he was secretly working for U.S. Army intelligence photographing German U-boats in Mexico. He was awarded the Bronze Star for heroism, rescuing American marines during the Battle of Tarawa while under heavy gunfire in 1943. He also lost a portion of his hearing from the noise of the battle.[7]

Aldrich Against the Army

THERE has been considerable talk

lately about the changing pattern

of production in Hollywood. The

old style of studio operation in

which

thirty or more pictures were

turned

out annually under the

supervisory

eye of a single executive

producer, it

would seem, is gradually giving

way to

a system of small, flexible units

built

around a star or a director who

acts

as his own producer on perhaps

one or

two films a year. We are, in

other

words, beginning to get

custom-made

films in quantity rather than the

longstandard

assembly-line jobs. Pictures

like "On the

Waterfront," "Marty,"

and "Moby Dick" are

representative of

the new trend—not only off-beat,

but

made with an individuality and

enthusiasm

that the larger studios can

rarely duplicate. Significantly,

within

the past year every one of the major

companies has added a number of

independent

productions to its releasing

schedule.

Behind this change is the firm of

United Artists. Formed in 1919 by

Charles Chaplin, Douglas

Fairbanks,

and Mary Pickford to handle the

distribution

of their own independently

made pictures, during the ensuing

quarter of a century it became

recognized

as the one real outlet for

quality

product. Goldwyn, Selznick,

Korda,

Disney—all the leading

independents

released through its facilities.

In the

years immediately after the war,

however,

the firm fell on evil days. With

its

original members either dead or

inactive

there just was not enough quality

production to support a large,

expensive

distribution organization.

Goldwyn,

Disney, and the others slipped

away to more profitable tie-ups

with

larger companies. By the late

Forties

the firm's position was

desperate.

When United Artists was

reorganized

in 1951 by two young lawyers,

Arthur Krim and Robert Benjamin,

they immediately substituted a

policy

of quantity for quality, building

up the

volume of their business to meet

the

overhead of a strong sales

organization.

By carefully nursing the better

films that came their way, and

boldly

exploiting such big ones as

"The African

Queen" and "Moulin

Rouge,"

Krim and Benjamin gradually wiped

away the tarnish that had

gathered on

the U.A. escutcheon. New

independent

outfits began to flock to its

banner—

some of them formed for capital

gains,

some by men who sincerely sought

a

greater freedom of expression on the

screen. Today U.A.'s roster of

independents

includes such names as Stanley

Kramer, Hecht-Lancaster, Joseph

Mankiewicz, Otto Preminger, and

Robert Aldrich—and its policy has

proven so profitable that it has

been

adopted by the industry at large.

Aldrich was in town recently, en

route to Los Angeles. He had just

spent eight hectic hours in Rome

arranging

for the screening of his latest

film, "Attack!," at the

Venice Festival.

He arrived in Rome, he said, at

three

p.m. the previous afternoon,

screened

his picture for the Festival

authorities,

caught a plane for New York at

eleven,

and was going on to Hollywood

that

very evening. All in the day's

worl

for an independent producer, h

seemed to imply, hooking his leg

ove

an arm of the chair he was

reclinin

in. A heavy-set man with thick,

horn

rimmed glasses and close-croppe^

1

brown hair, Aldrich is youthful,

se

rious, and outspoken. "Attack!"—lik

so many of the new independent

pro

ductions—is a controversial

picture, a

antiwar story in this day of Cold

Wa

militaristics, and Aldrich

prudentl

knocks wood every time he mention

the title. "The Army saw the

script,

he said with a wry smile,

"an 1

promptly laid down a policy of no

co

operation. Which not only meant

thf I

I couldn't borrow troops and

tanks fc

my picture—I couldn't even get a

lool

at Signal Corps combat footage. I

fi

nally had to buy a tank for

$1,000 an 1

rent another from 20th

Century-Fo;

Mine is parked now in my garagi

Know anybody who wants to buy

tank?" He poured himself a

cup t I

black coffee. "The joke of

it is th<

anybody could have stopped the

pic

ture cold for about $25,000, just

b

buying up all the uniforms."

IHE reasons for the Army's lack o^

enthusiasm are readily apparent.

Based on Norman Brook's play of a

few seasons ago, "Fragile

Fox," the

film deals with a cowardly

company

commander and an opportunistic

battalion

CO. who risks the life of every

man in the outfit by refusing to

relieve

his dangerously inept

subordinate. The

Captain's father, the CO.

explains to

an indignant lieutenant, heads

the political

machine back home and the

man can be very useful to him

once the war is over. When the Captain's

refusal to send promised support

to a

platoon cut off during an attack

results

in heavy losses the platoon

leader

swears personal vengeance.

"Attack!"

is hardly a recruiting poster for

the

U.S. Army. It is, on the other

hand, a tense and

throbbing drama, expertly acted

and

directed. Whether he saw Signal

Corps

footage or not Aldrich has

managed

his combat tactics—attacks on a

pillbox

and, later, on a strongly held

town

—with rare verisimilitude. Even

more

impressive is his handling of

strained

personal relationships against

the

background of the Bastogne

breakthrough—

the company Exec Officer

who recognizes his Captain's weakness

but respects the discipline of

rank,

the naked contempt of the

battalion

CO. for the man he hopes to use

to

his own advantage, the fierce

loyalty

of the platoon leader to his men.

All

of these are not simply stated;

they

unfold with the developing crisis

in

Fox Company, building to a climax

of

extraordinary—albeit melodramatic—

forcefulness. From his cast—Jack

Palance,

Eddie Albert, Lee Marvin, Buddy

Ebsen, and particularly William

Smithers as the hard-pressed Exec—

Aldrich has obtained a series of

superb

performances which he has

sustained

with strongly composed shots

and an imaginative use of natural

sound "Attack!" Aldrich

explained, cost

about $750,000 to produce—$50,000

above his anticipated budget. The

main part of the money was loaned

by

banks, with U.A. advancing the

additional

sum needed to complete the film.

If it succeeds there will be no

difficulty.

If not the loss comes out of his

own pocket. But Aldrich, like

many of

the independents, prefers to work

this

way, owning outright a

considerable

percentage of the film he directs

in lieu

of salary. Should the picture

prove a

hit he can use his equity in it

as collateral

for loans on future productions.

"It's a gamble,"

Aldrich admitted, "and

sometimes you lose—as I did on

'The

Big Knife.' On the other hand,

once

you get three aces back to back,

like

Hecht-Lancaster with 'Vera Cruz,'

'Marty,' and 'Trapeze,' then

you're

really set. You can do anything

you

want." He paused a moment to

reflect.

"Well, almost," he amended.

"There's still the problem

of distribution.

An independent doesn't get the

money to make his picture until

he

has some distribution deal set.

And

the people who decide what will

go

and what won't, I'm afraid, are

the

same fifteen men who dominated the

industry in the pre-independent

days

—shrewd, but still using the same

old

yardsticks. Sure, the independent

today

has more freedom to make what

he wants the way that he wants to

than

the fellows in the studios. But

three

aces back to back—that's rea\, independence."