https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus Julius Caesar held the office of dictator in perpetuity; technically, the constitution of the Roman Republic was still in effect during Caesar's relatively short time in power. His heir Augustus styled himself princeps, or "Leading Citizen," but is considered the first of the Imperial monarchs and reigned for more than 40 years. See Roman Emperor (Principate). Fergus Millar, "Ovid and the Domus Augusta: Rome Seen from Tomoi," Journal of Roman Studies 83 (1993), p. 6. Joseph Farrell, “The Augustan Period: 40 BC–AD 14,” in A Companion to Latin Literature (Blackwell, 2005), pp. 44–57Christopher Pelling, "The Triumviral Period," in The Cambridge Ancient History: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.–A.D. 69(Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 73 online. See also Farrell, "The Augustan Period."

War and expansion

Main article: Wars of Augustus

Further information: Roman–Persian relations

Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus choseImperator ("victorious commander") to be his first name, since he wanted to make an emphatically clear connection between himself and the notion of victory.[163] By the year 13, Augustus boasted 21 occasions where his troops proclaimed "imperator" as his title after a successful battle.[163] Almost the entire fourth chapter in his publicly released memoirs of achievements known as the Res Gestae was devoted to his military victories and honors.[163]

Augustus also promoted the ideal of a superior Roman civilization with a task of ruling the world (to the extent to which the Romans knew it), a sentiment embodied in words that the contemporary poet Virgil attributes to a legendary ancestor of Augustus: tu regere imperio populos, Romane, memento—"Roman, remember by your strength to rule the Earth's peoples!"[143] The impulse for expansionismapparently was prominent among all classes at Rome, and it is accorded divine sanction by Virgil's Jupiter in Book 1 of theAeneid, where Jupiter promises Rome imperium sine fine, "sovereignty without end".[164]

Conquering the peoples of the Alps in 16 BC was another important victory for Rome, since it provided a large territorial buffer between the Roman citizens of Italy and Rome's enemies in Germania to the north.[167] Horace dedicated an ode to the victory, while the monumentTrophy of Augustus near Monaco was built to honor the occasion.[168] The capture of the Alpine region also served the next offensive in 12 BC, when Tiberius began the offensive against the Pannonian tribes of Illyricum, and his brother Nero Claudius Drusus moved against the Germanic tribes of the eastern Rhineland.[169] Both campaigns were successful, as Drusus' forces reached the Elbe River by 9 BC—though he died shortly after by falling off his horse.[169] It was recorded that the pious Tiberius walked in front of his brother's body all the way back to Rome.[170]Yet arguably his greatest diplomatic achievement was negotiating with Phraates IV of Parthia (37–2 BC) in 20 BC for the return of the battle standards lost by Crassus in the Battle of Carrhae, a symbolic victory and great boost of morale for Rome.[170][171][172] Werner Eck claims that this was a great disappointment for Romans seeking to avenge Crassus' defeat by military means.[173] However, Maria Brosius explains that Augustus used the return of the standards as propagandasymbolizing the submission of Parthia to Rome. The event was celebrated in art such as the breastplate design on the statue Augustus of Prima Porta and in monuments such as the Temple of Mars Ultor ('Mars the Avenger') built to house the standards.[174

Parthia had always posed a threat to Rome in the east, but the real battlefront was along the Rhine and Danube rivers.[171]Before the final fight with Antony, Octavian's campaigns against the tribes in Dalmatia were the first step in expanding Roman dominions to the Danube.[175] Victory in battle was not always a permanent success, as newly conquered territories were constantly retaken by Rome's enemies in Germania.[171]

A prime example of Roman loss in battle was the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in AD 9, where three entire legions led byPublius Quinctilius Varus were destroyed by Arminius, leader of the Cherusci, an apparent Roman ally.[176] Augustus retaliated by dispatching Tiberius and Drusus to the Rhineland to pacify it, which had some success although the battle of AD 9 brought the end to Roman expansion into Germany.[177] Roman general Germanicus took advantage of a Cherusci civil war between Arminius and Segestes; they defeated Arminius, who fled that battle but was killed later in 21 due to treachery.[178]

Historian D. C. A. Shotter states that Augustus' policy of favoring the Julian family line over the Claudian might have afforded Tiberius sufficient cause to show open disdain for Augustus after the latter's death; instead, Tiberius was always quick to rebuke those who criticized Augustus.[199] Shotter suggests that Augustus' deification obliged Tiberius to suppress any open resentment that he might have harbored, coupled with Tiberius' "extremely conservative" attitude towards religion.[200]

Publicly, though, his last words were, "Behold, I found Augustus' Also, historian R. Shaw-Smith points to letters of Augustus to Tiberius which display affection towards Tiberius and high regard for his military merits.[201] Shotter states that Tiberius focused his anger and criticism on Gaius Asinius Gallus (for marrying Vipsania after Augustus forced Tiberius to divorce her), as well as toward the two young Caesars, Gaius and Lucius—instead of Augustus, the real architect of his divorce and imperial demotion.[200]famous last words were, "Have I played the part well? Then applaud as I exit"—referring to the play-acting and regal authority that he had put on as emperor.Behold, I found Rome of clay, and leave her to you of marble." An enormous funerary procession of mourners traveled with Augustus' body from Nola to Rome, and on the day of his burial all public and private businesses closed for the day.[197] Tiberius and his son Drusus delivered the eulogy while standing atop two rostra.[198] Augustus' body was coffin-bound and cremated on a pyre close to his mausoleum. It was proclaimed that Augustus joined the company of the gods as a member of the Roman pantheon.[198] The mausoleum was despoiled by the Goths in 410 during the Sack of Rome, and his ashes were scattered.

Legacy

Further information: Cultural depictions of Augustus

Augustus' reign laid the foundations of a regime that lasted, in one form or another, for nearly fifteen hundred years through the ultimate decline of the Western Roman Empire and until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. Both his adoptive surname, Caesar, and his title Augustus became the permanent titles of the rulers of the Roman Empire for fourteen centuries after his death, in use both at Old Rome and at New Rome. In many languages, Caesar became the word for Emperor, as in the German Kaiser and in the Bulgarian and subsequently Russian Tsar. The cult ofDivus Augustus continued until the state religion of the Empire was changed toChristianity in 391 by Theodosius I. Consequently, there are many excellent statues and busts of the first emperor. He had composed an account of his achievements, the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, to be inscribed in bronze in front of his mausoleum.[202]Copies of the text were inscribed throughout the Empire upon his death.[203] The inscriptions in Latin featured translations in Greek beside it, and were inscribed on many public edifices, such as the temple in Ankara dubbed the Monumentum Ancyranum, called the "queen of inscriptions" by historian Theodor Mommsen.[204]

]

There are a few known written works by Augustus that have survived such as his poems Sicily, Epiphanus, and Ajax, an autobiography of 13 books, a philosophical treatise, and his written rebuttal to Brutus' Eulogy of Cato.[205] Historians are able to analyze existing letters penned by Augustus to others for additional facts or clues about his personal life.[201][206]

Many consider Augustus to be Rome's greatest emperor; his policies certainly extended the Empire's life span and initiated the celebrated Pax Romana or Pax Augusta. The Roman Senate wished subsequent emperors to "be more fortunate than Augustus and better than Trajan". Augustus was intelligent, decisive, and a shrewd politician, but he was not perhaps as charismatic as Julius Caesar, and was influenced on occasion by his third wife, Livia (sometimes for the worse). Nevertheless, his legacy proved more enduring. The city of Rome was utterly transformed under Augustus, with Rome's first institutionalized police force, fire fighting force, and the establishment of the municipal prefect as a permanent office.[207] The police force was divided into cohorts of 500 men each, while the units of firemen ranged from 500 to 1,000 men each, with 7 units assigned to 14 divided city sectors.[207]

A praefectus vigilum, or "Prefect of the Watch" was put in charge of the vigiles, Rome's fire brigade and police.[208] With Rome's civil wars at an end, Augustus was also able to create a standing army for the Roman Empire, fixed at a size of 28 legions of about 170,000 soldiers.[209] This was supported by numerous auxiliary units of 500 soldiers each, often recruited from recently conquered areas.[210]

With his finances securing the maintenance of roads throughout Italy, Augustus also installed an official courier system of relay stations overseen by a military officer known as the praefectus vehiculorum.[211] Besides the advent of swifter communication among Italian polities, his extensive building of roads throughout Italy also allowed Rome's armies to march swiftly and at an unprecedented pace across the country.[212] In the year 6 Augustus established the aerarium militare, donating 170 million sesterces to the new military treasury that provided for both active and retired soldiers.[213]

One of the most enduring institutions of Augustus was the establishment of the Praetorian Guard in 27 BC, originally a personal bodyguard unit on the battlefield that evolved into an imperial guard as well as an important political force in Rome.[214] They had the power to intimidate the Senate, install new emperors, and depose ones they disliked; the last emperor they served was Maxentius, as it was Constantine I who disbanded them in the early 4th century and destroyed their barracks, the Castra Praetoria.[215]

Although the most powerful individual in the Roman Empire, Augustus wished to embody the spirit of Republican virtue and norms. He also wanted to relate to and connect with the concerns of the plebs and lay people. He achieved this through various means of generosity and a cutting back of lavish excess. In the year 29 BC, Augustus paid 400 sesterces each to 250,000 citizens, 1,000 sesterces each to 120,000 veterans in the colonies, and spent 700 million sesterces in purchasing land for his soldiers to settle upon.[216] He also restored 82 different temples to display his care for the Roman pantheon of deities.[216] In 28 BC, he melted down 80 silver statues erected in his likeness and in honor of him, an attempt of his to appear frugal and modest.[216]

The longevity of Augustus' reign and its legacy to the Roman world should not be overlooked as a key factor in its success. As Tacitus wrote, the younger generations alive in AD 14 had never known any form of government other than the Principate.[217] Had Augustus died earlier (in 23 BC, for instance), matters might have turned out differently. The attrition of the civil wars on the old Republican oligarchy and the longevity of Augustus, therefore, must be seen as major contributing factors in the transformation of the Roman state into a de facto monarchy in these years. Augustus' own experience, his patience, his tact, and his political acumen also played their parts. He directed the future of the Empire down many lasting paths, from the existence of a standing professional army stationed at or near the frontiers, to the dynastic principle so often employed in the imperial succession, to the embellishment of the capital at the emperor's expense. Augustus' ultimate legacy was the peace and prosperity the Empire enjoyed for the next two centuries under the system he initiated. His memory was enshrined in the political ethos of the Imperial age as a paradigm of the good emperor. Every Emperor of Rome adopted his name, Caesar Augustus, which gradually lost its character as a name and eventually became a title.[198] The Augustan era poets Virgil and Horace praised Augustus as a defender of Rome, an upholder of moral justice, and an individual who bore the brunt of responsibility in maintaining the empire.[218]However, for his rule of Rome and establishing the principate, Augustus has also been subjected to criticism throughout the ages. The contemporary Roman jurist Marcus Antistius Labeo (d. AD 10/11), fond of the days of pre-Augustan republicanliberty in which he had been born, openly criticized the Augustan regime.[219] In the beginning of his Annals, the Roman historian Tacitus (c. 56–c.117) wrote that Augustus had cunningly subverted Republican Rome into a position of slavery.[219]He continued to say that, with Augustus' death and swearing of loyalty to Tiberius, the people of Rome simply traded one slaveholder for another.[219] Tacitus, however, records two contradictory but common views of Augustus:

List of Augustan writers[edit]Augustus' famous last words were, "Have I played the part well? Then applaud as I exit"—referring to the play-acting and regal authority that he had put on as emperor.

- Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil, spelled also as Vergil) (70 – 19 BC),

- Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace) (65 – 8 BC), known for lyric poetry and satires

- Sextus Aurelius Propertius (50 – 15 BC), poet

- Albius Tibullus (54 – 19 BC), elegiac poet

- Titus Livius (Livy) (64 BC – 12 AD), historian

- Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid) (43 BC – 18 AD), poet

- Grattius Faliscus (a contemporary of Ovid), poet

- Marcus Manilius (1st century BC & AD), astrologer, poet

- Gaius Julius Hyginus (64 BC – 17 AD), librarian, poet, mythographer

- Marcus Verrius Flaccus (55 BC – 20 AD), grammarian, philologist, calendrist

- Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80 70 BC – after 15 BC), engineer, architect

- Marcus Antistius Labeo (d. 10 or 11 AD), jurist, philologist

- Lucius Cestius Pius (1st century BC & AD), Latin educator

- Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus (1st century BC), historian, naturalist

- Marcus Porcius Latro (1st century BC), rhetorician

- Gaius Valgius Rufus (consul 12 BC), poet

Christopher Pelling, "The Triumviral Period," inThe Cambridge Ancient History: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.–A.D. 69 (Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 73 online. See also Farrell, "The Augustan Period."

Augustan literature (ancient Rome)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

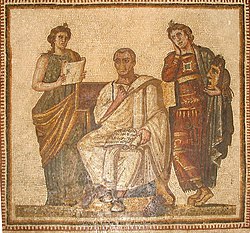

Augustan literature is the period of Latin literature written during the reign ofAugustus (27 BC–AD 14), the first Roman emperor.[1] In literary histories of the first part of the 20th century and earlier, Augustan literature was regarded along with that of the Late Republic as constituting the Golden Age of Latin literature, a period of stylistic classicism.[2]

Most of the literature periodized as Augustan was in fact written by men—Vergil,Horace, Propertius, Livy—whose careers were established during the triumviralyears, before Octavian assumed the title Augustus. Strictly speaking, Ovid is the poet whose work is most thoroughly embedded in the Augustan regime.[3]

Impact and style[edit]

Augustan literature produced the most widely read, influential, and enduring of Rome’s poets. The Republican poets Catullus and Lucretius are their immediate predecessors; Lucan, Martial, Juvenal and Statius are their so-called "Silver Age" heirs. Although Vergil has sometimes been considered a “court poet,” his Aeneid, the most important of the Latin epics, also permits complex readings on the source and meaning of Rome’s power and the responsibilities of a good leader.[4]

Ovid’s works were wildly popular, but the poet was exiled by Augustus in one of literary history’s great mysteries; carmen et error (“a poem” or “poetry” and “a mistake”) is Ovid’s own oblique explanation. Among prose works, the monumental historyof Livy is preeminent for both its scope and stylistic achievement. The multivolume work On Architecture by Vitruvius remains of great informational interest.[5]

Questions pertaining to tone, or the writer's attitude toward his subject matter, are acute among the preoccupations of scholars who study the period. In particular, Augustan works are analyzed in an effort to understand the extent to which they advance, support, criticize or undermine social and political attitudes promulgated by the regime, official forms of which were often expressed in aesthetic media.[6]

List of Augustan writers[edit]

- Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil, spelled also as Vergil) (70 – 19 BC),

- Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace) (65 – 8 BC), known for lyric poetry and satires

- Sextus Aurelius Propertius (50 – 15 BC), poet

- Albius Tibullus (54 – 19 BC), elegiac poet

- Titus Livius (Livy) (64 BC – 12 AD), historian

- Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid) (43 BC – 18 AD), poet

- Grattius Faliscus (a contemporary of Ovid), poet

- Marcus Manilius (1st century BC & AD), astrologer, poet

- Gaius Julius Hyginus (64 BC – 17 AD), librarian, poet, mythographer

- Marcus Verrius Flaccus (55 BC – 20 AD), grammarian, philologist, calendrist

- Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80 70 BC – after 15 BC), engineer, architect

- Marcus Antistius Labeo (d. 10 or 11 AD), jurist, philologist

- Lucius Cestius Pius (1st century BC & AD), Latin educator

- Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus (1st century BC), historian, naturalist

- Marcus Porcius Latro (1st century BC), rhetorician

- Gaius Valgius Rufus (consul 12 BC), poet

References[edit]

- ^ Julius Caesar held the office of dictator in perpetuity; technically, the constitution of the Roman Republic was still in effect during Caesar's relatively short time in power. His heir Augustus styled himself princeps, or "Leading Citizen," but is considered the first of the Imperial monarchs and reigned for more than 40 years. See Roman Emperor (Principate).

- ^ Fergus Millar, "Ovid and the Domus Augusta: Rome Seen from Tomoi," Journal of Roman Studies 83 (1993), p. 6.

- ^ Fergus Millar, "Ovid and the Domus Augusta: Rome Seen from Tomoi," Journal of Roman Studies 83 (1993), p. 6.

- ^ Joseph Farrell, “The Augustan Period: 40 BC–AD 14,” in A Companion to Latin Literature (Blackwell, 2005), pp. 44–57.

- ^ Joseph Farrell, “The Augustan Period: 40 BC–AD 14,” in A Companion to Latin Literature (Blackwell, 2005), pp. 44–57.

- ^ Christopher Pelling, "The Triumviral Period," in The Cambridge Ancient History: The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.–A.D. 69(Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 73 online. See also Farrell, "The Augustan Period."

Augustus (Latin: Imperātor Caesar Dīvī Fīlius Augustus;[note 1][note 2] 23 September 63 BC – 19 August 14 AD) was the founder of the Roman Empireand its first Emperor, ruling from 27 BC until his death in AD 14.[note 3]

He was born Gaius Octavius into an old and wealthy equestrian branch of theplebeian Octavii family. His maternal great-uncle Julius Caesar wasassassinated in 44 BC, and Octavius was named in Caesar's will as hisadopted son and heir, then known as Octavianus (Anglicized as Octavian). He, Mark Antony, and Marcus Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate to defeat the assassins of Caesar. Following their victory at Philippi, the Triumvirate divided the Roman Republic among themselves and ruled asmilitary dictators.[note 4] The Triumvirate was eventually torn apart under the competing ambitions of its members. Lepidus was driven into exile and stripped of his position, and Antony committed suicide following his defeat at the Battle of Actium by Octavian in 31 BC.

The statue known as the Augustus of Prima Porta, 1st century

| |||||

| 1st Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reign | 16 January 27 BC – 19 August AD 14 (40 years) | ||||

| Successor | Tiberius | ||||

| Born | Gaius Octavius 23 September 63 BC Rome, Roman Republic | ||||

| Died | 19 August AD 14 (aged 75) Nola, Italia, Roman Empire | ||||

| Burial | Mausoleum of Augustus, Rome | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Julio-Claudian Dynasty | ||||

| Father |

| ||||

| Mother | Atia Balba Caesonia | ||||

| Religion | Traditional ancient Roman religion | ||||

After the demise of the Second Triumvirate, Augustus restored the outward facade of the free Republic, with governmental power vested in the Roman Senate, the executive magistrates, and the legislative assemblies. In reality, however, he retained his autocratic power over the Republic as a military dictator. By law, Augustus held a collection of powers granted to him for life by the Senate, including supreme military command, and those of tribune andcensor. It took several years for Augustus to develop the framework within which a formally republican state could be led under his sole rule. He rejected monarchical titles, and instead called himself Princeps Civitatis ("First Citizen of the State"). The resulting constitutional framework became known as thePrincipate, the first phase of the Roman Empire.

The reign of Augustus initiated an era of relative peace known as the Pax Romana (The Roman Peace). The Roman world was largely free from large-scale conflict for more than two centuries, despite continuous wars of imperial expansion on the Empire's frontiers and one year-long civil war over the imperial succession. Augustus dramatically enlarged the Empire, annexingEgypt, Dalmatia, Pannonia, Noricum, and Raetia; expanding possessions inAfrica; expanding into Germania; and completing the conquest of Hispania.

Beyond the frontiers, he secured the Empire with a buffer region of client states and made peace with the Parthian Empire through diplomacy. He reformed the Roman system of taxation, developed networks of roads with an official courier system, established a standing army, established the Praetorian Guard, created official police and fire-fighting services for Rome, and rebuilt much of the city during his reign.

Augustus died in AD 14 at the age of 75. He may have died from natural causes, although there were unconfirmed rumors that his wife Livia poisoned him. He was succeeded as Emperor by his adopted son (also stepson and former son-in-law) Tiberius.

Augustus (/ɔːˈɡʌstəs/;[1] Classical Latin: [awˈɡʊstʊs]) was known by many names throughout his life:[note 1]

- At birth, he was named Gaius Octavius after his biological father. Historians typically refer to him simply as Octavius(or Octavian) between his birth in 63 until his adoption by Julius Caesar in 44 BC (after Julius Caesar's death).

- Upon his adoption, he took Caesar's name and became Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus in accordance with Roman adoption naming standards. He quickly dropped "Octavianus" from his name, and his contemporaries typically referred to him as "Caesar" during this period; historians, however, refer to him as Octavian between 44 BC and 27 BC.[2]

- In 42 BC, Octavian began the Temple of Divus Iulius or Temple of the Comet Star[3] and added Divi Filius (Son of the Divine) to his name in order to strengthen his political ties to Caesar's former soldiers by following the deification of Caesar, becoming Gaius Julius Caesar Divi Filius.

- In 38 BC, Octavian replaced his praenomen "Gaius" and nomen "Julius" with Imperator, the title by which troops hailed their leader after military success, officially becoming Imperator Caesar Divi Filius.

- In 27 BC, following his defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, the Roman Senate voted new titles for him, officially becoming Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus.[note 2] It is the events of 27 BC from which he obtained his traditional name of Augustus, which historians use in reference to him from 27 BC until his death in AD 14.

Early life

Main article: Early life of Augustus

While his paternal family was from the town of Velletri, approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) from Rome, Augustus was born in the city of Rome on 23 September 63 BC.[4] He was born at Ox Head, a small property on the Palatine Hill, very close to theRoman Forum. He was given the name Gaius Octavius Thurinus, his cognomen possibly commemorating his father's victory at Thurii over a rebellious band of slaves.[5][6]

Due to the crowded nature of Rome at the time, Octavius was taken to his father's home village at Velletri to be raised. Octavius only mentions his father's equestrian family briefly in his memoirs. His paternal great-grandfather Gaius Octaviuswas a military tribune in Sicily during the Second Punic War. His grandfather had served in several local political offices. His father, also named Gaius Octavius, had been governor of Macedonia.[note 5][7] His mother, Atia, was the niece of Julius Caesar.

Julia died in 52 or 51 BC, and Octavius delivered the funeral oration for his grandmother.[10] From this point, his mother and stepfather took a more active role in raising him. He donned the toga virilis four years later,[11] and was elected to theCollege of Pontiffs in 47 BC.[12][13] The following year he was put in charge of theGreek games that were staged in honor of the Temple of Venus Genetrix, built by Julius Caesar.[13] According to Nicolaus of Damascus, Octavius wished to join Caesar's staff for his campaign in Africa, but gave way when his mother protested.[14] In 46 BC, she consented for him to join Caesar in Hispania, where he planned to fight the forces of Pompey, Caesar's late enemy, but Octavius fell ill and was unable to travel.

Heir to Caesar

Octavius was studying and undergoing military training in Apollonia,Illyria, when Julius Caesar was killed on the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC. He rejected the advice of some army officers to take refuge with the troops in Macedonia and sailed to Italy to ascertain whether he had any potential political fortunes or security.[17] Caesar had no living legitimate children under Roman law,[note 6] and so had adoptedOctavius, his grand-nephew, making him his primary heir.[18] Mark Antony later charged that Octavian had earned his adoption by Caesar through sexual favours, though Suetonius describes Antony's accusation as political slander.[19] After landing at Lupiae nearBrundisium, Octavius learned the contents of Caesar's will, and only then did he decide to become Caesar's political heir as well as heir to two-thirds of his estate.[13][17][20]

Upon his adoption, Octavius assumed his great-uncle's name Gaius Julius Caesar. Roman citizens adopted into a new family usually retained their old nomen in cognomen form (e.g.,Octavianus for one who had been an Octavius, Aemilianus for one who had been an Aemilius, etc.). However, though some of his contemporaries did,[21] there is no evidence that Octavius ever himself officially used the name Octavianus, as it would have made his modest origins too obvious.[22][23][24] Historians usually refer to the new Caesar as Octavian during the time between his adoption and his assumption of the name Augustus in 27 BC in order to avoid confusing the dead dictator with his heir.[25]

Octavian could not rely on his limited funds to make a successful entry into the upper echelons of the Roman political hierarchy.[26] After a warm welcome by Caesar's soldiers at Brundisium,[27] Octavian demanded a portion of the funds that were allotted by Caesar for the intended war against Parthia in the Middle East.[26] This amounted to 700 million sestercesstored at Brundisium, the staging ground in Italy for military operations in the east.[28]

A later senatorial investigation into the disappearance of the public funds took no action against Octavian, since he subsequently used that money to raise troops against the Senate's arch enemy Mark Antony.[27] Octavian made another bold move in 44 BC when, without official permission, he appropriated the annual tribute that had been sent from Rome'sNear Eastern province to Italy.[23][29]

Octavian began to bolster his personal forces with Caesar's veteran legionaries and with troops designated for the Parthian war, gathering support by emphasizing his status as heir to Caesar.[17][30] On his march to Rome through Italy, Octavian's presence and newly acquired funds attracted many, winning over Caesar's former veterans stationed in Campania.[23] By June, he had gathered an army of 3,000 loyal veterans, paying each a salary of 500 denarii.[31][32][33]

Growing tensions

Arriving in Rome on 6 May 44 BC,[23] Octavian found consul Mark Antony, Caesar's former colleague, in an uneasy truce with the dictator's assassins. They had been granted a general amnesty on 17 March, yet Antony succeeded in driving most of them out of Rome.[23] This was due to his "inflammatory" eulogy given at Caesar's funeral, mounting public opinion against the assassins.[23]

Mark Antony was amassing political support, but Octavian still had opportunity to rival him as the leading member of the faction supporting Caesar. Mark Antony had lost the support of many Romans and supporters of Caesar when he initially opposed the motion to elevate Caesar to divine status.[34] Octavian failed to persuade Antony to relinquish Caesar's money to him. During the summer, he managed to win support from Caesarian sympathizers, however, who saw the younger heir as the lesser evil and hoped to manipulate him, or to bear with him during their efforts to get rid of Antony.[35]Octavian began to make common cause with the Optimates, the former enemies of Caesar. In September, the leading Optimate orator Marcus Tullius Cicero began to attack Antony in aseries of speeches portraying him as a threat to the Republican order.[36][37] With opinion in Rome turning against him and his year of consular power nearing its end, Antony attempted to pass laws that would lend him control over Cisalpine Gaul, which had been assigned as part of his province, from Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, one of Caesar's assassins.[38][39]Octavian meanwhile built up a private army in Italy by recruiting Caesarian veterans and, on 28 November, he won over two of Antony's legions with the enticing offer of monetary gain.[40][41][42] In the face of Octavian's large and capable force, Antony saw the danger of staying in Rome and, to the relief of the Senate, he fled to Cisalpine Gaul, which was to be handed to him on 1 January.[42]

First conflict with Antony

Decimus Brutus refused to give up Cisalpine Gaul, so Antony besieged him at Mutina.[43]Antony rejected the resolutions passed by the Senate to stop the violence, as the Senate had no army of its own to challenge him. This provided an opportunity for Octavian, who already was known to have armed forces.[41] Cicero also defended Octavian against Antony's taunts about Octavian's lack of noble lineage and aping of Julius Caesar's name, stating "we have no more brilliant example of traditional piety among our youth."[44]

At the urging of Cicero, the Senate inducted Octavian as senator on 1 January 43 BC, yet he also was given the power to vote alongside the former consuls.[41][42] In addition, Octavian was granted propraetor imperium (commanding power) which legalized his command of troops, sending him to relieve the siege along with Hirtius and Pansa (the consuls for 43 BC).[41][45] In April 43 BC, Antony's forces were defeated at the battles ofForum Gallorum and Mutina, forcing Antony to retreat to Transalpine Gaul. Both consuls were killed, however, leaving Octavian in sole command of their armies.[46][47]

The senate heaped many more rewards on Decimus Brutus than on Octavian for defeating Antony, then attempted to give command of the consular legions to Decimus Brutus—yet Octavian decided not to cooperate.[48] Instead, Octavian stayed in the Po Valley and refused to aid any further offensive against Antony.[49] In July, an embassy of centurions sent by Octavian entered Rome and demanded that he receive the consulship left vacant by Hirtius and Pansa.[50]

Octavian also demanded that the decree should be rescinded which declared Antony a public enemy.[49] When this was refused, he marched on the city with eight legions.[49] He encountered no military opposition in Rome, and on 19 August 43 BC was elected consul with his relative Quintus Pedius as co-consul.[51][52] Meanwhile, Antony formed an alliance withMarcus Aemilius Lepidus, another leading Caesarian.[53]

In a meeting near Bologna in October 43 BC, Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus formed a junta called the Second Triumvirate.[55] This explicit arrogation of special powers lasting five years was then supported by law passed by the plebs, unlike the unofficial First Triumvirate formed by Pompey, Julius Caesar, and Marcus Licinius Crassus.[55][56] The triumvirs then set in motion proscriptions in which 300 senators and 2,000 equites allegedly were branded as outlaws and deprived of their property and, for those who failed to escape, their lives.[57]

The estimation that 300 senators were proscribed was presented by Appian, although his earlier contemporary Livy asserted that only 130 senators had been proscribed.[58] This decree issued by the triumvirate was motivated in part by a need to raise money to pay the salaries of their troops for the upcoming conflict against Caesar's assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus.[59] Rewards for their arrest gave incentive for Romans to capture those proscribed, while the assets and properties of those arrested were seized by the triumvirs.[57]

Contemporary Roman historians provide conflicting reports as to which triumvir was more responsible for the proscriptions and killing. However, the sources agree that enacting the proscriptions was a means by all three factions to eliminate political enemies.[60] Marcus Velleius Paterculus asserted that Octavian tried to avoid proscribing officials whereas Lepidus and Antony were to blame for initiating them.[61] Cassius Dio defended Octavian as trying to spare as many as possible, whereas Antony and Lepidus, being older and involved in politics longer, had many more enemies to deal with.[61]

This claim was rejected by Appian, who maintained that Octavian shared an equal interest with Lepidus and Antony in eradicating his enemies.[62] Suetonius presented the case that Octavian, although reluctant at first to proscribe officials, nonetheless pursued his enemies with more rigor than the other triumvirs.[60] Plutarch described the proscriptions as a ruthless and cutthroat swapping of friends and family among Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian. For example, Octavian allowed the proscription of his ally Cicero, Antony the proscription of his maternal uncle Lucius Julius Caesar (the consul of 64 BC), and Lepidus his brother Paullus.[61]

Battle of Philippi and division of territory

Further information: Liberators' civil war

On 1 January 42 BC, the Senate posthumously recognized Julius Caesar as a divinity of the Roman state, Divus Iulius. Octavian was able to further his cause by emphasizing the fact that he was Divi filius, "Son of God".[63] Antony and Octavian then sent 28 legions by sea to face the armies of Brutus and Cassius, who had built their base of power in Greece.[64] After two battles at Philippi in Macedonia in October 42, the Caesarian army was victorious and Brutus and Cassius committedsuicide. Mark Antony later used the examples of these battles as a means to belittle Octavian, as both battles were decisively won with the use of Antony's forces.[65] In addition to claiming responsibility for both victories, Antony also branded Octavian as a coward for handing over his direct military control to Marcus Vipsanius Agrippainstead.[65]

After Philippi, a new territorial arrangement was made among the members of the Second Triumvirate. Gaul and the provinces of Hispania and Italia were placed in the hands of Octavian. Antony traveled east to Egypt where he allied himself with Queen Cleopatra VII, the former lover of Julius Caesar and mother of Caesar's infant son Caesarion. Lepidus was left with the province of Africa, stymied by Antony, who conceded Hispania to Octavian instead.[66]

Octavian was left to decide where in Italy to settle the tens of thousands of veterans of the Macedonian campaign, whom the triumvirs had promised to discharge. The tens of thousands who had fought on the republican side with Brutus and Cassius could easily ally with a political opponent of Octavian if not appeased, and they also required land.[66] There was no more government-controlled land to allot as settlements for their soldiers, so Octavian had to choose one of two options: alienating many Roman citizens by confiscating their land, or alienating many Roman soldiers who could mount a considerable opposition against him in the Roman heartland. Octavian chose the former.[67] There were as many as eighteen Roman towns affected by the new settlements, with entire populations driven out or at least given partial evictions.[68]

Rebellion and marriage alliances

There was widespread dissatisfaction with Octavian over these settlements of his soldiers, and this encouraged many to rally at the side of Lucius Antonius, who was brother of Mark Antony and supported by a majority in the Senate.[68]Meanwhile, Octavian asked for a divorce from Clodia Pulchra, the daughter of Fulvia (Mark Antony's wife) and her first husband Publius Clodius Pulcher. He returned Clodia to her mother, claiming that their marriage had never been consummated. Fulvia decided to take action. Together with Lucius Antonius, she raised an army in Italy to fight for Antony's rights against Octavian. Lucius and Fulvia took a political and martial gamble in opposing Octavian, however, since the Roman army still depended on the triumvirs for their salaries.[68] Lucius and his allies ended up in a defensive siege atPerusia (modern Perugia), where Octavian forced them into surrender in early 40 BC.[68]

Lucius and his army were spared, due to his kinship with Antony, the strongman of the East, while Fulvia was exiled toSicyon.[69] Octavian showed no mercy, however, for the mass of allies loyal to Lucius; on 15 March, the anniversary of Julius Caesar's assassination, he had 300 Roman senators and equestrians executed for allying with Lucius.[70] Perusia also was pillaged and burned as a warning for others.[69] This bloody event sullied Octavian's reputation and was criticized by many, such as Augustan poet Sextus Propertius.[70]

Sextus Pompeius was the son of First Triumvir Pompey and still a renegade general following Julius Caesar's victory over his father. He was established in Sicily and Sardinia as part of an agreement reached with the Second Triumvirate in 39 BC.[71]Both Antony and Octavian were vying for an alliance with Pompeius, who was a member of the republican party, ironically, not the Caesarian faction.[70] Octavian succeeded in a temporary alliance in 40 BC when he married Scribonia, a daughter of Lucius Scribonius Libo who was a follower of Sextus Pompeius as well as his father-in-law.[70] Scribonia gave birth to Octavian's only natural child, Julia, who was born the same day that he divorced her to marry Livia Drusilla, little more than a year after their marriage.[70]

While in Egypt, Antony had been engaged in an affair with Cleopatra and had fathered three children with her.[72] Aware of his deteriorating relationship with Octavian, Antony left Cleopatra; he sailed to Italy in 40 BC with a large force to oppose Octavian, laying siege to Brundisium. This new conflict proved untenable for both Octavian and Antony, however. Their centurions, who had become important figures politically, refused to fight due to their Caesarian cause, while the legions under their command followed suit.[73][74] Meanwhile, in Sicyon, Antony's wife Fulvia died of a sudden illness while Antony was en route to meet her. Fulvia's death and the mutiny of their centurions allowed the two remaining triumvirs to effect a reconciliation.[73][74]

In the autumn of 40, Octavian and Antony approved the Treaty of Brundisium, by which Lepidus would remain in Africa, Antony in the East, Octavian in the West. The Italian peninsula was left open to all for the recruitment of soldiers, but in reality, this provision was useless for Antony in the East.[73] To further cement relations of alliance with Mark Antony, Octavian gave his sister, Octavia Minor, in marriage to Antony in late 40 BC.[73] During their marriage, Octavia gave birth to two daughters (known as Antonia Major and Antonia Minor).

War with Pompeius

Further information: Sicilian revolt

Sextus Pompeius threatened Octavian in Italy by denying shipments of grain through the Mediterranean to the peninsula. Pompeius' own son was put in charge as naval commander in the effort to cause widespread famine in Italy.[74] Pompeius' control over the sea prompted him to take on the name Neptuni filius, "son of Neptune".[75]A temporary peace agreement was reached in 39 BC with the treaty of Misenum; the blockade on Italy was lifted once Octavian granted Pompeius Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, and the Peloponnese, and ensured him a future position as consul for 35 BC.[74][75]The territorial agreement between the triumvirate and Sextus Pompeius began to crumble once Octavian divorced Scribonia and married Livia on 17 January 38 BC.[76] One of Pompeius' naval commanders betrayed him and handed over Corsica and Sardinia to Octavian. Octavian lacked the resources to confront Pompeius alone, however, so an agreement was reached with the Second Triumvirate's extension for another five-year period beginning in 37 BC.[56][77]In supporting Octavian, Antony expected to gain support for his own campaign against Parthia, desiring to avenge Rome'sdefeat at Carrhae in 53 BC.[77] In an agreement reached at Tarentum, Antony provided 120 ships for Octavian to use against Pompeius, while Octavian was to send 20,000 legionaries to Antony for use against Parthia.[78] Octavian sent only a tenth of those promised, however, which Antony viewed as an intentional provocation.[78]

War with Antony

Main article: Final War of the Roman Republic

Meanwhile, Antony's campaign turned disastrous against Parthia, tarnishing his image as a leader, and the mere 2,000 legionaries sent by Octavian to Antony were hardly enough to replenish his forces.[83] On the other hand, Cleopatra could restore his army to full strength; he already was engaged in a romantic affair with her, so he decided to send Octavia back to Rome.[84] Octavian used this to spreadpropaganda implying that Antony was becoming less than Roman because he rejected a legitimate Roman spouse for an "Oriental paramour".[85] In 36 BC, Octavian used a political ploy to make himself look less autocratic and Antony more the villain by proclaiming that the civil wars were coming to an end, and that he would step down as triumvir—if only Antony would do the same. Antony refused.[86]Roman troops captured the Kingdom of Armenia in 34 BC, and Antony made his son Alexander Helios the ruler of Armenia. He also awarded the title "Queen of Kings" to Cleopatra, acts that Octavian used to convince the Roman Senate that Antony had ambitions to diminish the preeminence of Rome.[85] Octavian became consul once again on 1 January 33 BC, and he opened the following session in the Senate with a vehement attack on Antony's grants of titles and territories to his relatives and to his queen.[87]

The breach between Antony and Octavian prompted a large portion of the Senators, as well as both of that year's consuls, to leave Rome and defect to Antony. However, Octavian received two key deserters from Antony in the autumn of 32 BC: Munatius Plancus and Marcus Titius.[88] These defectors gave Octavian the information that he needed to confirm with the Senate all the accusations that he made against Antony.[89]Octavian forcibly entered the temple of the Vestal Virgins and seized Antony's secret will, which he promptly publicized. The will would have given away Roman-conquered territories as kingdoms for his sons to rule, and designated Alexandria as the site for a tomb for him and his queen.[90][91] In late 32 BC, the Senate officially revoked Antony's powers as consul and declared war on Cleopatra's regime in Egypt.[92][93]

Bibliography

- Allen, William Sidney (1978) [1965]. Vox Latina—a Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37936-9.

- Ando, Clifford, Imperial ideology and provincial loyalty in the Roman Empire, University of California Press, 2000.

- Bivar, A. D. H. (1983). "The Political History of Iran Under the Arsacids", in The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol 3:1), 21–99. Edited by Ehsan Yarshater. London, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, and Sydney: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- Blackburn, Bonnie and Holford-Strevens, Leofranc. (1999). The Oxford Companion to the Year. Oxford University Press. Reprinted with corrections 2003.

- Bourne, Ella. "Augustus as a Letter-Writer", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association (Volume 49, 1918): 53–66.

- Bowersock, G. W. (1990). "The Pontificate of Augustus". In Kurt A. Raaflaub and Mark Toher (eds.). Between Republic and Empire: Interpretations of Augustus and his Principate. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 380–394.ISBN 978-0-520-08447-6.

- Brosius, Maria. (2006). The Persians: An Introduction. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32089-4 (hbk).

- Bunson, Matthew. (1994). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. New York: Facts on File Inc. ISBN 978-0-8160-3182-5

- Chisholm, Kitty and John Ferguson. (1981). Rome: The Augustan Age; A Source Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press, in association with the Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-872108-6

- Dio, Cassius. (1987) The Roman History: The Reign of Augustus. Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044448-3.

- Davies, Mark; Swain, Hilary; Davies, Mark Everson, Aspects of Roman history, 82 BC-AD 14: a source-based approach, Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2010.

- Eck, Werner; translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider; new material by Sarolta A. Takács. (2003) The Age of Augustus. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-631-22957-5; paperback, ISBN 978-0-631-22958-2).

- Eder, Walter. (2005). "Augustus and the Power of Tradition", inThe Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus (Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World), ed. Karl Galinsky, 13–32. Cambridge, MA; New York: Cambridge University Press (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-521-80796-8; paperback, ISBN 978-0-521-00393-3).

- Everitt, Anthony (2006) Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor. Random House Books. ISBN 1-4000-6128-8.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05611-6.

- Gruen, Erich S. (2005). "Augustus and the Making of the Principate", in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus (Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World), ed. Karl Galinsky, 33–51. Cambridge, MA; New York: Cambridge University Press (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-521-80796-8; paperback, ISBN 978-0-521-00393-3).

- Holland, Richard, Augustus, Godfather of Europe, Sutton Publishing, 2005.

- Kelsall, Malcolm. "Augustus and Pope", The Huntington Library Quarterly (Volume 39, Number 2, 1976): 117–131.

- Mackay, Christopher S. (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80918-4.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Toher, Mark, Between republic and empire: interpretations of Augustus and his principate, University of California Press, 1993.

- Rowell, Henry Thompson. (1962). The Centers of Civilization Series: Volume 5; Rome in the Augustan Age. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-0956-5

- Scott, Kenneth. "The Political Propaganda of 44–30 B.C."Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 11, (1933), pp. 7–49.

- Scullard, H. H. (1982) [1959]. From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 (5th ed.). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-02527-0.

- Suetonius, Gaius Tranquillus (2013) [1913]. Thayer, Bill, ed.The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. J. C. Rolfe, trans. University of Chicago. Original publisher Loeb Classical Library.

- Suetonius, Gaius Tranquillus (1931). Lives of the Twelve Caesars. New York: Modern Library.

- Shaw-Smith, R. "A Letter from Augustus to Tiberius", Greece & Rome (Volume 18, Number 2, 1971): 213–214.

- Shotter, D. C. A. "Tiberius and the Spirit of Augustus", Greece & Rome (Volume 13, Number 2, 1966): 207–212.

- Smith, R. R. R., "The Public Image of Licinius I: Portrait Sculpture and Imperial Ideology in the Early Fourth Century",The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 87, (1997), pp. 170–202,JSTOR

- Southern, Pat. (1998). Augustus. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16631-7.

- Starr, Chester G., Jr. "The Perfect Democracy of the Roman Empire", The American Historical Review (Volume 58, Number 1, 1952): 1–16.

- Syme, Ronald (1939). The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280320-4.

- Walker, Susan, and Burnett, Andrew, The Image of Augustus, 1981, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0-7141-1270-4

- Wells, Colin Michael, The Roman Empire, Harvard University Press, 2004.

Bibliography

- Allen, William Sidney (1978) [1965]. Vox Latina—a Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37936-9.

- Ando, Clifford, Imperial ideology and provincial loyalty in the Roman Empire, University of California Press, 2000.

- Bivar, A. D. H. (1983). "The Political History of Iran Under the Arsacids", in The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol 3:1), 21–99. Edited by Ehsan Yarshater. London, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, and Sydney: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- Blackburn, Bonnie and Holford-Strevens, Leofranc. (1999). The Oxford Companion to the Year. Oxford University Press. Reprinted with corrections 2003.

- Bourne, Ella. "Augustus as a Letter-Writer", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association (Volume 49, 1918): 53–66.

- Bowersock, G. W. (1990). "The Pontificate of Augustus". In Kurt A. Raaflaub and Mark Toher (eds.). Between Republic and Empire: Interpretations of Augustus and his Principate. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 380–394.ISBN 978-0-520-08447-6.

- Brosius, Maria. (2006). The Persians: An Introduction. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32089-4 (hbk).

- Bunson, Matthew. (1994). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. New York: Facts on File Inc. ISBN 978-0-8160-3182-5

- Chisholm, Kitty and John Ferguson. (1981). Rome: The Augustan Age; A Source Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press, in association with the Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-872108-6

- Dio, Cassius. (1987) The Roman History: The Reign of Augustus. Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044448-3.

- Davies, Mark; Swain, Hilary; Davies, Mark Everson, Aspects of Roman history, 82 BC-AD 14: a source-based approach, Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2010.

- Eck, Werner; translated by Deborah Lucas Schneider; new material by Sarolta A. Takács. (2003) The Age of Augustus. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-631-22957-5; paperback, ISBN 978-0-631-22958-2).

- Eder, Walter. (2005). "Augustus and the Power of Tradition", inThe Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus (Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World), ed. Karl Galinsky, 13–32. Cambridge, MA; New York: Cambridge University Press (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-521-80796-8; paperback, ISBN 978-0-521-00393-3).

- Everitt, Anthony (2006) Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor. Random House Books. ISBN 1-4000-6128-8.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05611-6.

- Gruen, Erich S. (2005). "Augustus and the Making of the Principate", in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus (Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World), ed. Karl Galinsky, 33–51. Cambridge, MA; New York: Cambridge University Press (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-521-80796-8; paperback, ISBN 978-0-521-00393-3).

- Holland, Richard, Augustus, Godfather of Europe, Sutton Publishing, 2005.

- Kelsall, Malcolm. "Augustus and Pope", The Huntington Library Quarterly (Volume 39, Number 2, 1976): 117–131.

- Mackay, Christopher S. (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80918-4.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Toher, Mark, Between republic and empire: interpretations of Augustus and his principate, University of California Press, 1993.

- Rowell, Henry Thompson. (1962). The Centers of Civilization Series: Volume 5; Rome in the Augustan Age. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-0956-5

- Scott, Kenneth. "The Political Propaganda of 44–30 B.C."Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 11, (1933), pp. 7–49.

- Scullard, H. H. (1982) [1959]. From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 (5th ed.). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-02527-0.

- Suetonius, Gaius Tranquillus (2013) [1913]. Thayer, Bill, ed.The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. J. C. Rolfe, trans. University of Chicago. Original publisher Loeb Classical Library.

- Suetonius, Gaius Tranquillus (1931). Lives of the Twelve Caesars. New York: Modern Library.

- Shaw-Smith, R. "A Letter from Augustus to Tiberius", Greece & Rome (Volume 18, Number 2, 1971): 213–214.

- Shotter, D. C. A. "Tiberius and the Spirit of Augustus", Greece & Rome (Volume 13, Number 2, 1966): 207–212.

- Smith, R. R. R., "The Public Image of Licinius I: Portrait Sculpture and Imperial Ideology in the Early Fourth Century",The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 87, (1997), pp. 170–202,JSTOR

- Southern, Pat. (1998). Augustus. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16631-7.

- Starr, Chester G., Jr. "The Perfect Democracy of the Roman Empire", The American Historical Review (Volume 58, Number 1, 1952): 1–16.

- Syme, Ronald (1939). The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280320-4.

- Walker, Susan, and Burnett, Andrew, The Image of Augustus, 1981, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0-7141-1270-4

- Wells, Colin Michael, The Roman Empire, Harvard University Press, 2004.

Further reading

- Bleicken, Jochen. (1998). Augustus. Eine Biographie. Berlin.

- Buchan, John (1937). Augustus. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Everitt, Anthony. The First Emperor: Caesar Augustus and the Triumph of Rome. London: John Murray, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7195-5495-7.

- Galinsky, Karl. Augustan Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998 (paperback, ISBN 978-0-691-05890-0).

- Galinsky, Karl (2012). Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor. Cambridge University Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-521-74442-3.

- Grant, Michael (1985). The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome, 31 BC — AD 476. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Levick, Barbara. Augustus: Image and Substance. London: Longman, 2010. ISBN 978-0-582-89421-1.

- Lewis, P. R. and G. D. B. Jones, Roman gold-mining in north-west Spain, Journal of Roman Studies 60 (1970): 169–85

- Jones, R. F. J. and Bird, D. G., Roman gold-mining in north-west Spain, II: Workings on the Rio Duerna, Journal of Roman Studies 62 (1972): 59–74.

- Jones, A. H. M. "The Imperium of Augustus", The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 41, Parts 1 and 2. (1951), pp. 112–119.

- Jones, A. H. M. Augustus. London: Chatto & Windus, 1970 (paperback, ISBN 978-0-7011-1626-2).

- Massie, Allan (1984). The Caesars. New York: Franklin Watts.

- Osgood, Josiah. Caesar's Legacy: Civil War and the Emergence of the Roman Empire. New York: Cambridge University Press (USA), 2006 (hardback, ISBN 978-0-521-85582-2; paperback, ISBN 978-0-521-67177-4).

- Raaflaub, Kurt A. and Toher, Mark (eds.). Between Republic and Empire: Interpretations of Augustus and His Principate. Berkeley; Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993 (paperback, ISBN 978-0-520-08447-6).

- Reinhold, Meyer. The Golden Age of Augustus (Aspects of Antiquity). Toronto, ON: Univ. of Toronto Press, 1978 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-89522-007-3; paperback, ISBN 978-0-89522-008-0).

- Roebuck, C. (1966). The World of Ancient Times. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Shotter, D. C. A. (1991). Augustus Caesar. Lancaster Pamphlets. London: Routledge.

- Southern, Pat. Augustus (Roman Imperial Biographies). New York: Routledge, 1998 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-415-16631-7); 2001 (paperback, ISBN 978-0-415-25855-5).

- Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (Thomas Spencer Jerome Lectures). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1989 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-472-10101-6); 1990 (paperback, ISBN 978-0-472-08124-0).

External links

External links

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| News from Wikinews | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Texts from Wikisource | |

- Primary sources

- Cassius Dio's Roman History: Books 45–56, English translation

- Gallery of the Ancient Art: August

- Humor of Augustus

- Life of Augustus by Nicolaus of Damascus, English translation

- Suetonius' biography of Augustus, Latin text with English translation

- The Res Gestae Divi Augusti (The Deeds of Augustus, his own account: complete Latin and Greek texts with facing English translation)

- The Via Iulia Augusta: road built by the Romans; constructed on the orders of Augustus between the 13–12 B.C.