Plot[edit]

| The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

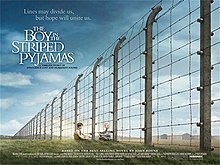

Theatrical release poster

| |||||||

| Directed by | Mark Herman

| ||||||

| Produced by | David Heyman | ||||||

| Screenplay by | Mark Herman | ||||||

| Based on | The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas by John Boyne | ||||||

| Starring | |||||||

| Music by | James Horner | ||||||

| Cinematography | Benoît Delhomme | ||||||

| Edited by | Michael Ellis | ||||||

Production

company | |||||||

| Distributed by | Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures | ||||||

Release dates

|

| ||||||

Running time

| 94 minutes | ||||||

| Country | United Kingdom | ||||||

| Language | English | ||||||

| Budget | $12.5 million[1] | ||||||

| Box office | $44 million[2] | ||||||

Bruno is a nine-year-old boy growing up during World War II in Berlin. He lives with his parents, his 12-year-old sister Gretel and maids, one of whom is called Maria. After a visit by Adolf Hitler, Bruno's father is promoted to Commandant, and the family has to move to 'Out-With' because of the orders of "The Fury" (Bruno's naïve interpretation of the word 'Führer'). Bruno is initially upset about moving to Out-With (never identified, but cf. Auschwitz[4]) and leaving his friends, Daniel, Karl, and Martin. From the house at Out-With, Bruno sees a camp. One day, Bruno decides to explore the strange wire fence. As he walks along the fence, he meets a Jewish boy named Shmuel, who he learns shares his birthday. Shmuel says that his father, grandfather, and brother are with him on this side of the fence, but he is separated from his mother. Bruno and Shmuel talk and become very good friends, although Bruno still does not understand very much about Shmuel and his side of the fence. Nearly every day, unless it's raining Bruno goes to see Shmuel and sneaks him food. As the meetings go on, and Shmuel gets more and more skinny, Bruno's naïveteshows that his innocence has been preserved despite being near a death camp.

Plot[edit]

An 8-year-old boy named Bruno (Asa Butterfield) lives with his family in Berlin, in Nazi Germany during the Holocaust. He learns that his father Ralf (David Thewlis) has been promoted, due to which their family, including Bruno's mother Elsa (Vera Farmiga) and 12-year-old sister Gretel (Amber Beattie), relocate to the countryside. Bruno hates his new home as there is no one to play with and very little to explore. After commenting that he has spotted people working on what he thinks is a farm in the distance, he is also forbidden from playing in the back garden.

Bruno and Gretel get a tutor, Herr Liszt (Jim Norton), who pushes an agenda of antisemitism and nationalist propaganda. Gretel becomes increasingly fanatical in her support for the Third Reich, covering her bedroom wall with Nazi propaganda posters. Bruno is confused as the Jews he has seen, in particular the family's Jewish servant Pavel (David Hayman), do not resemble the caricatures in Liszt's teachings

One day, Bruno disobeys his parents and sneaks off into the woods, eventually arriving at an electric barbed wire fence surrounding a camp. He befriends a boy his own age named Schmuel (Jack Scanlon). The pair's lack of knowledge on the true nature of the camp is revealed: Bruno thinks that the striped uniforms that Schmuel, Pavel, and the other prisoners wear are pyjamas and Schmuel believes his grandparents died from an illness during their journey to the camp. Bruno starts meeting Schmuel regularly, sneaking him food and playing board games with him. He eventually learns that Schmuel is a Jew and was brought to the camp with his father.

One day, Elsa discovers the reality of Ralf's assignment after Lieutenant Kurt Kotler (Rupert Friend) lets slip that the black smoke coming from the camp's chimneys is due to the burning corpses of Jews. She confronts Ralf, disgusted and heartbroken. At dinner that night, Kotler admits that his father had left his family and moved toSwitzerland. Upon hearing this, Ralf tells Kotler he should have informed the authorities of his father's disagreement with the current political regime as it was his duty. The embarrassed Kotler then uses Pavel's spilling of a wine glass as an excuse to beat the inmate to prove his support of the regime. The next morning the maid, Maria, is seen scrubbing the blood stains.

Later the next day, Bruno sees Schmuel working in his home. Schmuel is there to clean wine glasses because they needed someone with small hands to do it. Bruno offers him some cake and willingly Schmuel accepts it. Unfortunately, Kotler happens to walk into the room where Bruno and Schmuel are socializing. Kotler is furious and yells at Schmuel for talking to Bruno. In the midst of his scolding, Kotler notices Schmuel chewing the food Bruno gave him. When Kotler asks Schmuel where he got the food, he says Bruno offered the cake, but Bruno, fearful of Kotler, denies this. Believing Bruno, Kotler tells Schmuel that they will have a "little chat" later. Distraught, Bruno goes to apologize to Schmuel, but finds him gone. Every day, Bruno returns to the same spot by the camp but does not see Schmuel. Eventually, Schmuel reappears behind the fence, sporting a black eye. Bruno apologizes and Schmuel forgives him, renewing the friendship.

After the funeral of Bruno's grandmother, who was killed in Berlin by an enemy bombing, Ralf tells Bruno and Gretel that their mother suggests that they go live with a relative because it isn't safe there. Their mother suggests this because she doesn't want her children living with their murderous father. Schmuel has problems of his own; his father has gone missing after those with whom he participated in a march did not return to the camp. Bruno decides to redeem himself by helping Schmuel find his father. The next day, Bruno, who is due to leave that afternoon, dons a striped prisoners' outfit and a cap to cover his unshaven hair, and digs under the fence to join Schmuel in the search. Bruno soon discovers the true nature of the camp after seeing the many sick and weak-looking Jews. While searching, the boys are taken on a march with other inmates by Sonderkommandos.

At the house, Gretel and Elsa discover Bruno's disappearance, and Elsa bursts into Ralf's meeting to alert him that Bruno is missing. Ralf and his men mount a search and find Bruno's discarded clothing outside the fence. They enter the camp, looking for him; Bruno, Schmuel and the other inmates are stopped inside a changing room and are told to remove their clothes for a "shower". They are packed into a gas chamber, where Bruno and Schmuel hold each other's hands. An SSsoldier pours some Zyklon B pellets inside, and the prisoners start yelling and banging on the metal door. When Ralf realizes that a gassing is taking place, he cries out his son's name, and Elsa and Gretel fall to their knees in despair. The film ends by showing the closed door of the now-silent gas chamber, indicating that the prisoners, Schmuel and Bruno, are dead.

Cast[edit]

- Asa Butterfield as Bruno

Asa Butterfield

Butterfield at the 2014 Toronto International Film FestivalBorn Asa Maxwell Thornton Farr Butterfield

1 April 1997

Islington, London, England, United KingdomOccupation Actor Years active 2006–present Filmography[edit]

Film[edit]

Year Title Role Notes 2007 Son of Rambow Brethren Boy 2008 The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas Bruno 2010 The Wolfman Younger Ben Talbot 2010 Nanny McPhee and the Big Bang Norman Green 2011 Hugo Hugo Cabret 2013 Ender's Game Ender Wiggin 2014[29] X+Y[30] Nathan Ellis also known as A Brilliant Young Mind[31] 2015 Ten Thousand Saints Jude Keffy-Horn 2016 Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children Jacob Portman 2016 The Space Between Us Gardner Elliot Post-Production Television[edit]

Year Title Role Notes and awards 2006 After Thomas Andrew Television film 2008 Ashes to Ashes Donny Episode #1.6 2008–09 Merlin Mordred 3 episodes - Jack Scanlon as Schmuel, a young Jew sent to a camp

Filmography[edit]

Film[edit]

Year Film Roles 2008 The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas Shmuel Television[edit]

Year Programme Role 2007 Peter Serafinowicz Show Various roles 2009 Runaway Dean 2010 Married Single Other Joe - Vera Farmiga as Elsa, Bruno's mother

Vera Farmiga

Farmiga in November 2011Born Vera Ann Farmiga

August 6, 1973

Clifton, New Jersey, U.S.Alma mater Syracuse University Occupation - Actress

- director

- producer

Years active 1996–present Spouse(s) - Sebastian Roché (m. 1997–2004)

- Renn Hawkey (m. 2008)

Children 2 Relatives - Taissa Farmiga (sister)

- Adriana Farmiga (cousin)

- Molly Hawkey (sister-in-law)

Filmography[edit]

Main article: Vera Farmiga filmography- Return to Paradise (1998)

- Autumn in New York (2000)

- 15 Minutes (2001)

- Dummy (2002)

- Down to the Bone (2004)

- The Manchurian Candidate (2004)

- Running Scared (2006)

- The Departed (2006)

- Never Forever (2007)

- The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (2008)

- Orphan (2009)

- Up in the Air (2009)

- Henry's Crime (2010)

- Higher Ground (2011)

- Source Code (2011)

- Safe House (2012)

- The Conjuring (2013)

- At Middleton (2013)

- The Judge (2014)

- Special Correspondents (2016)

- The Conjuring 2 (2016)

- Burn Your Maps (2016)

- Boundaries (2017)

- The Commuter (2017)

- David Thewlis as Ralf, Bruno's father

David Thewlis

Thewlis at the 2008 San Sebastian Film FestivalBorn David Wheeler

20 March 1963

Blackpool, Lancashire, EnglandOccupation Actor, author, film director, screenwriter Years active 1985–present Spouse(s) Sara Sugarman (m. 1992;div. 1993) Partner(s) Anna Friel (2001–2010) Children 1 Filmography[edit]

Film[edit]

- Amber Beattie as Gretel, Bruno's sister

- Rupert Friend as Lieutenant Kurt Kotler

- David Hayman as Pavel

- Sheila Hancock as Natalie, Bruno's grandmother

- Richard Johnson as Matthias, Bruno's grandfather

- Cara Horgan as Maria

- Jim Norton as Herr Liszt

Historical accuracy[edit]

Some critics have criticized the premise of the book and subsequent film. Reviewing the original book, Rabbi Benjamin Blechwrote: "Note to the reader: There were no 9-year-old Jewish boys in Auschwitz – the Nazis immediately gassed those not old enough to work."[8] Rabbi Blech affirmed the opinion of a Holocaust survivor friend that the book is "not just a lie and not just a fairytale, but a profanation." Blech acknowledges the objection that a "fable" need not be factually accurate; he counters that the book trivializes the conditions in and around the death camps and perpetuates the "myth that those [...] not directly involved can claim innocence," and thus undermines its moral authority. Students who read it, he warns, may believe the camps "weren't that bad" if a boy could conduct a clandestine friendship with a Jewish captive of the same age, unaware of "the constant presence of death."[9] Blech, Benjamin (23 October 2008). "The Boy in the Striped Pajamas". Aish.com. Retrieved 11 February2013.

But, according to the memoirs of several Auschwitz-Birkenau survivors, a few young children did live in the camp: "The oldest children were 16, and 52 were less than 8 years of age. Some children were employed as camp messengers and were treated as a kind of curiosity, while every day an enormous number of children of all ages were killed in the gas chambers."[10][11] Langbein, Hermann; Zohn, Harry (Translator) (2004).People in Auschwitz. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill. ISBN 0-8078-2816-5. Buergentha, Thomas (2009). A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy. London: Profile.ISBN 1-84668-178-2.

Kathryn Hughes, whilst agreeing about the implausibility of the plot, argues that "Bruno's innocence comes to stand for the willful refusal of all adult Germans to see what was going on under their noses."[12] In the Chicago Sun-Times Roger Ebert, says the film is not a reconstruction of Germany during the war, but is "about a value system that survives like a virus."[13] Ebert, Roger (5 November 2008). "The Boy in the Striped Pajamas". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (released as The Boy in the Striped Pajamas in the United States; see spelling difference) is a 2008 Britishhistorical period drama based on the novel of the same name by Irish writerJohn Boyne.[3] Vilkomerson, Sara (31 March 2009).Week: Lost Boys". The "On Demand This New York Observer. Retrieved4 July 2011. Directed by Mark Herman, produced by Miramax Films, and distributed by Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, the film stars Vera Farmiga, David Thewlis, Asa Butterfield, and Jack Scanlon. It was released on 12 September 2008 in the United Kingdom.

The film is a Holocaust drama that explores the horror of a World War II Naziextermination camp through the eyes of two 8-year-old boys; one the son of the camp's Nazi commandant (Butterfield), the other a Jewish inmate(Scanlon).

References[edit]

- ^ "The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (2008)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (2008) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ Vilkomerson, Sara (31 March 2009). "On Demand This Week: Lost Boys". The New York Observer. Retrieved4 July 2011.

- ^ "The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (2008)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Christopher, James (11 September 2008). "The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas Review". The Times. Archived fromthe original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 30 August2009.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (7 November 2008). "Horror Through a Child's Eyes". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 August2009.

- ^ Blech, Benjamin (23 October 2008). "The Boy in the Striped Pajamas". Aish.com. Archived from the originalon 30 August 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Blech, Benjamin (23 October 2008). "The Boy in the Striped Pajamas". Aish.com. Retrieved 11 February2013.

- ^ Langbein, Hermann; Zohn, Harry (Translator) (2004).People in Auschwitz. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill. ISBN 0-8078-2816-5.

- ^ Buergentha, Thomas (2009). A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy. London: Profile.ISBN 1-84668-178-2.

- ^ Hughes, Kathryn (21 January 2006). "Educating Bruno".The Guardian.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (5 November 2008). "The Boy in the Striped Pajamas". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ BIFA 2008 Nominations at British Independent Film Awards

- ^ "2009 Winners—Film Categories". The Irish Film & Television Academy.

- ^ "2009 Nominations & Recipients". Young Artist Awards.

_(english).jpg)