http://www.dutch-east-indies.com/story/index.htm

INDEX OF ARTICLES

|

BBC Homepage BBC History | ||

| WW2 People's War HomepageArchive ListTimelineAbout This SitePrint this page | ||

Contact Us Like this page? Send it to a friend! http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/user/07/u1652307.shtml | ||

TJIDENG REUNION: A MEMOIR OF WW II ON JAVA

POSTS TAGGED AS:

Tjimahi

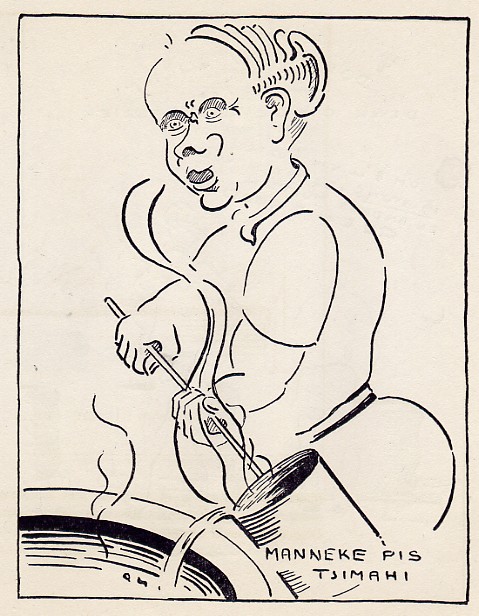

In my book I say very little about the men’s camp, Tjimahi, where my father was interned. These two pictures however are referred to (but are not reproduced) in the book.

Some clever chemist in the men’s camp had worked out a process for producing a liquid yeast from urine. This discovery has been immortalized in these two pictures.

One is an image of the presumed chemist, also referrred to in the caption as “manneke pis”. That name would have been familiar to anyone living or growing up in the Netherlands or Belgium. In a corner of the Grand Place of Brussels there stands a bronze statue of a little boy (it is also a little statue- half a meter tall) peeing day and night, and that statue has the same name. It is a relic from World War 1 and was erected by a company of soldier who had befriended the boy- probably an orphan.

The other caption says something to the effect of : “Do your duty gentlemen, otherwise no bread tomorrow.” For about six months our women’s camp received a daily supply of this yeast for breadmaking from Tjimahi (about 10 km away). It was delivered on the back of an improvised truck made by replacing the rear end of an automobile with a flat bed, and contained in one or two 45 gallon drums.

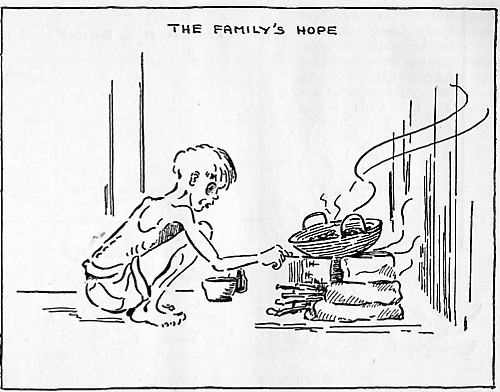

The cartoons were drawn by M.G. Hartley between 1942 and 1945.

These images relate to Bandung and our time there. We were first interned in the city where we were living, Bandung, and only in May 1945, shortly before the end of the war, were moved to Batavia ( Jakarta) and the Tjideng Camp.

As I got older during my internment period, I began to fear the day I would become ten years old, for that meant, becoming independent and leaving the care of my mother. I of course had no idea what such an experience would mean for me, and that may be just as well because the truth of what happened to these youngsters defies belief. Those who physically survived the experience never recovered from the psychological damage.

I was lucky and celebrated my tenth birthday after the war.

Mr. Hartley (Myn Kamp, niet door Hilter, Amsterdamsche Boek en Courant Maatschappij, 1947), who drew this cartoon of one such pathetic youngster who happened to be interned in Tjimahi, a Men’s camp where my father also was, gave the experience a bitter twist.

His caption reads: Many a mothers’ heart would have swelled with pride had she been able to see her dear son’s culinary achievements. It was not just that the raw materials had been obtained via devious means, but the provision of fuel would likely have involved even less elegant techniques: chairs, tables, windows, wooden shoes, all sacrificed for a meal.

TJIDENG REUNION: A MEMOIR OF WW II ON JAVA

Books of Note

The Diary of Prisoner 17326 by John K. Stutterheim, Fordham University Press , New York 2010.

John Stutterheim was born in 1928 , and therefore was fourteen years old when he and his mother and younger brother were ordered out of their home in Malang, Eastern Java, by the invading Japanese army. Thus began their internment, taking them to Surabaja, and Solo. Eventually John was ordered to leave his mother and go to a boy’s camp, where he had the presence of mind, and tenacity to maintain a diary, complete with sketches. This book therefore gives a rare, detailed glimpse of the horrors experienced by boys in those camps and moreover provides information about internment in eastern and central Java . This book is a good read .

In Deze Halve Gevangenis, (In this half Prison), a Diary by Dr. L. F. Jansen, Annotated by G. J. Knaap, Uitgeverij van Wijnen, Franeker, 1988 (CIP/ISBN 90 5194 016 5).

This is a most remarkable account of a little known aspect the Japanese occupation of South East Asia, unfortunately only available in Dutch. At the outbreak of the Pacific War, Leo Jansen, a recent arrival in the Netherlands East Indies, had thanks to his legal education and a gift for language, acquired a senior admininstrative position in the Netherlands East Indies Colonial Government. This, along with his near fluency in Japanese and Malay (inn addition to his excellent command of French, German and English) made him a prime target for rendering assistance to the Japanese propaganda work , centred in Jakarta. Refusal to participate in this form of forced collaboration was not an option, but Leo’s reputation was such that the Japanese Director offered him limited choice: he need not broadcast propaganda. His task was to translate Allied broadcasts into Japanese.

The Japanese Propaganda Bureau had three objectives: to create despondency among European listeners ( especially in Australia), to assure Indonesian listeners and readers of Japan”s assured victory and to ‘hide from Japanese troops the scale of Japanese reversals. Leo, having a modest amount of freedom of action, had daily dinner table discussions with his English, Dutch, Singhalese, Indonesian and Japanese counterparts, which he confides to his secret diary on a daily basis and in great detail. The discussions range over politics, the progress of the war, nationalist movements and philosophy. Leo’s final undoing was the fact that he knew too much and attempted to alert the Allies about the chilly reception they could expect after Japanese capitulation in Indonesia. He was apprehended, suffered torture at the hands of the kempetai (the Japanese military police).

Assisted by a Eurasian girl friend and a sympathetic Japanese soldier he barely survived the war, only to suffer a mis-diagnosis in hospital after liberation.

The story of how this remarkably insightful diary survived the war, eventually was found and after years of research, placed within the proper historic context of occupied Java is almost as amazing as the contents.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment